When Carolyn Sheltered in Place

Robert Wexelblatt

She tried to think of things that made her happy. None of them made her happy. Not recalling the night she stayed up reading all of Black Beauty, not her first boyfriend Philip or Gil, her last one. She tried reconstructing the glorious night freshman year when she and her roommate Sharon got drunk, staggered back to the dorm laughing through the streets of Ann Arbor, and bonded, telling each other absolutely everything. Now Sharon lived in Napa Valley with her veterinarian husband, matching chocolate labs, and two little girls. The last time they’d Facetimed, Carolyn told her about Magyar, the new three-star restaurant in SoHo with goulash to die for, and Sharon talked about cute toddler words and what the vet did to her dogs. Carolyn supposed that the veterinarians of California never went unemployed, unlike the graphic designers, campaign workers, key grips, hungry agents and famished actors. Sharon sounded busy, happy in her exhaustion, secure in her sunbathed life.

Carolyn was suddenly routineless, laid off, unpaid, as alone as the loneliest of everyone else. It was if the curtain had crashed down in the middle of the Second Act. People always think plagues won’t come back and every war’s the one that’ll end all wars. But wars and epidemics are like earthquakes and hurricanes; there are always more of them.

More and more often, Carolyn’s mind became unbridled, floating. One dreary afternoon, it drifted to Dürer’s apocalyptic woodcuts she remembered from Art History. The Four Horsemen Ride Again, she whispered. It alarmed her that the words actually came out, that she didn’t just think them. Once, when she was a child, she had seen a man talking to himself and thought he was talking to her. Her mother had pulled her away and whispered that only crazy people talked to themselves. She wondered if we always remember those things our mothers whisper to us.

To Carolyn it was a revelation that you could be scared and bored at the same time. For a while, she thought about that, how, physiologically, it could be possible when being scared makes you alert and quick while boredom makes you dull and languorous. Thinking about her brain and its three parts made her drowsy. So much did. Carolyn worried that she was sleeping too much: a nap in the morning and another in the afternoon, a full nine hours every night. Her schedule had become that of old ladies and infants, opposites that meet on a circle of somnolence.

Like a child who scarfs down a tub of vanilla ice cream and can’t look at the stuff for a decade, Carolyn had had enough of phone calls, Facebook, emails, tweets, people posting upbeat snapshots and desperately cheery videos, dancers collaborating over continents, orchestras playing from bedrooms. One morning she didn’t even boot up then, later, feeling it a momentous act, switched off her I-phone. She didn’t want any more distraction; it felt like evasion. She would keep up with the news on radio, all the news that wasn’t directed just at her.

She missed her mother but hadn’t phoned her in weeks. There wasn’t any point in trying. She felt like a motherless child and hummed the tune.

She put water on for tea, turned on the radio, heard the latest tally. Monty Python. Bring out your dead. She carried her cup of tea to the window, pulled back the curtain and looked down on the lifeless, neutron-bombed street. Everything was the same as yesterday and the day before, even the trash in the gutters.

She lay down on her bed. No need to pull the sheets tight, for hospital corners, to tuck the blanket in; no need to shampoo either, put on makeup, pick out tomorrow’s outfit. She only had to wash her hands, spray doorknobs, mask-up and venture out for food. Shopping had become foraging. The idea of a shopping list now seemed ludicrous. You searched for what you could use in what little was there.

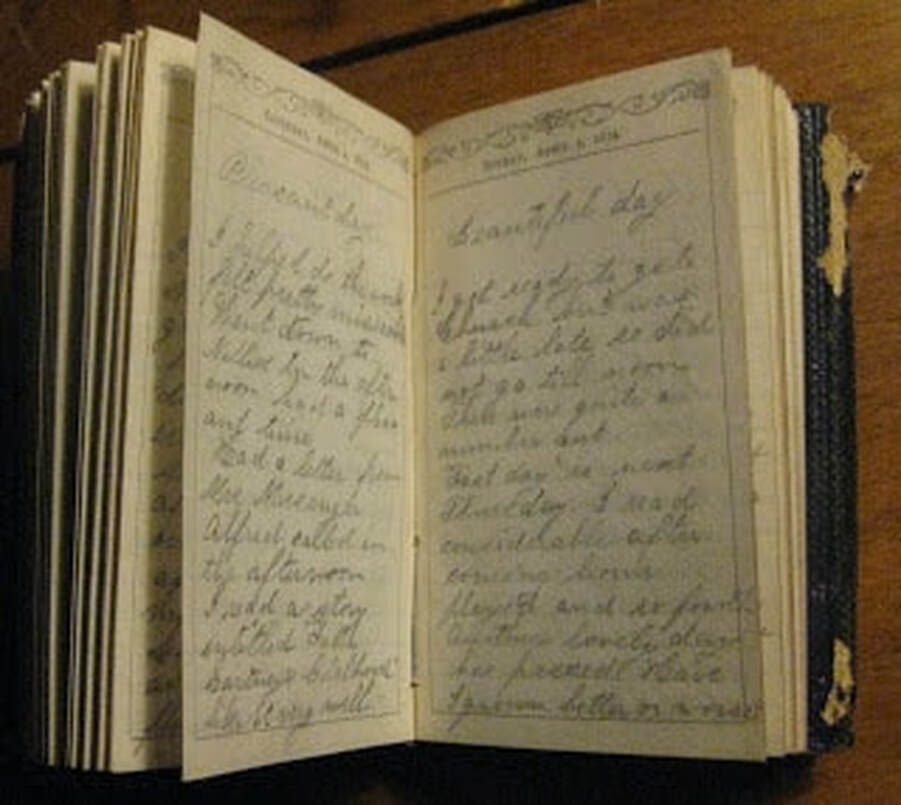

She lay on her back and thought of her sophomore year, the one when she had tried to keep a journal. Perhaps the journal popped into her mind because writing in it was the last time life had seemed so—she struggled for a word—interior. But keeping at the journal was too hard; she was lazy and rationalized that living was better than thinking about living. There were parties, dates, two clubs, homework, exams. She had written in one those expensive Moleskine books, with a narrow black ribbon to mark pages, like a bible. Her father had sent it to her for her eighteenth birthday. That made it five years before he died and nine before her widowed mother married Ben, a nice man with an unfortunate mustache. He had died too and only a year after the quiet wedding.

Carolyn realized now that her father probably intended the notebook as an encouragement, something to make her more reflective. Her father had “Carolyn’s Journal” put on the cover in gold letters. She took it as an assignment and also a criticism. Her father had been a professor of Greek and Roman history, and it disappointed him that she had zero interest in his wars and emperors and was only attracted by the myths, which she called “those old fairy tales.” Still, because she loved her father, she’d forced herself to keep up the journal for a long time, well at least for a few months.

Carolyn found it easy to drop the tiller of her mind, especially when she was supine. Journals are to diaries as films are to movies, she mused, as ships are to boats, hotels to motels. The analogies were her favorite section of the SAT. Journals are to diaries. . .

Feeling a sudden urgency, Carolyn leapt off the bed. She needed to see that journal pronto. Finding it wasn’t a whim but the immediate focus of her day. If she’d saved it, the book would be in one of the cartons down in the storage locker. She threw on her yellow hoodie, her mask, grabbed her keys, opened the door gingerly and made sure the hallway was empty. Then she dashed to the elevator, waited for it, tapping her foot impatiently. When it finally came, she jabbed the BB button.

The sub-basement was humid and there were cockroach corpses against the walls and in the corners. The fluorescent lighting was spotty, flickery. Her locker looked like rubble. It took her half an hour to find the book. What a relief! Though it smelled of mildew and the pages had curled, her handwriting was legible—far clearer than it was now.

She flipped though the book. Ouf, she said out loud. She’d barely covered thirty pages; she hadn’t even kept it up for a whole month.

She closed up the carton, hastily restacked it, and carried the journal back to the elevator, resolved to go through it before lunch.

Most of what she read was embarrassing, the log of a lingering post-adolescence, a chronicle of parties, gossip, whining, callow philosophizing, fleeting enthusiasms, judgments both mean and superficial. What she had written wasn’t a journal at all; it was only a diary. But then she came to the next-to-last entry, the longest in the book and the only one she would not have been ashamed for her father to read.

A red-letter day. Prof. Krasnow and Prof. Washburn both said something memorable at the end of their lectures, nearly a pair of proverbs. Krasnow delivered a survey of utopianism from Plato to Pol Pot. At the end, he said, “No perfect society is good, and no good society is perfect.”

Washburn’s lecture was supposed to be about Heinrich von Kleist’s play, The Prince of Homburg, which I really liked and wanted to learn more about; but, as usual, she wandered far afield. I can’t decide whether her digressions are down to advancing age, intellectual scope or just exuberance. No matter. Before dismissing the class, she turned her Athena-face on us. “Nobility,” she said sternly, “has nothing to do with happiness. Nobility’s an attitude toward unhappiness.”

I agree with Krasnow up to a point. I mean I’m not a fan of totalitarian idealism either. But he’s settled into what looks like a tweedy and self-satisfied middle-age. He’s a bit too comfortable with human imperfection. His thinking’s like a well-upholstered easy chair. Maybe because I’m young what’s imperfect makes me indignant and angry; I feel like protesting, not shrugging. Krasnow likes Aristotle and dislikes Plato and no wonder. I think Aristotle must have been born middle-aged; and, though he’s right about a lot, that’s mostly because his teacher was so much more brilliantly wrong.

As for what Prof. Washburn said about nobility and unhappiness—it’s made me think, though not really about either. It started me thinking about solitude, which is lovely, and loneliness which is a kind of sadness. Maybe the only difference between them is just that one makes you unhappy and the other doesn’t. I think of myself as outgoing and sociable, and yet there have always been times when I’ve yearned to be left alone, all alone, to be free of my parents, cousins, friends, classmates—free of everybody.

Mother phoned tonight about the credit card and said I was ungrateful. I had a fight with Scott yesterday and, for no reason at all, Sharon was snippy with me at dinner.

Solitude sounds like bliss; and yet, I wonder. If it turned into loneliness, could I face it with nobility?

Carolyn closed the book and started to weep. She didn’t mean to. She wept for herself, her father, for Ben and her thrice-bereaved mother who had lost two husbands and then her memory. She no longer remembered that she had a daughter. She wept for the people in the hospitals struggling to breathe and the exhausted nurses trying to keep them alive. She pulled herself together and rubbed away her tears. There’s nothing noble in weeping.

She went to the kitchen and wrapped the journal in tin foil, the way you do leftovers, then stuffed it in a drawer between sweaters.

Years later, when Carolyn had married and had a little boy, when she was a wife and mother and stopped being an orphan, nobody wanted to recall that time, the perilous hiatus of isolation. What with her job and friends, the club and the baby, she was always busy and hardly ever alone.

When Chip got a promotion, and Carolyn was planning a dinner party to celebrate, she remembered a wedding gift, a pair of silver candlesticks that would make her table look more elegant. She had put them away and never used them. They would be in one of the boxes in the basement.

The first carton she opened contained old serving forks and spoons. The second was full of her old sweaters. They made her feel sentimental, nostalgic. She pulled out a gray turtleneck and then smiled at the mauve cardigan that her mother had hated. And there, on top of a white cotton pullover, was the moleskin journal still wrapped up tight, sealed off and put away like a leftover pot roast.

Carolyn unwrapped the journal and remembered the lockdown, her studio apartment, how it felt then. She opened the book, her father’s gift, his assignment, and saw again how little she’d written. She read her criticism of Professor Krasnow’s comfort with imperfection and the tragic words of Professor Washburn. They both felt like a reproof.

Robert Wexelblatt

She tried to think of things that made her happy. None of them made her happy. Not recalling the night she stayed up reading all of Black Beauty, not her first boyfriend Philip or Gil, her last one. She tried reconstructing the glorious night freshman year when she and her roommate Sharon got drunk, staggered back to the dorm laughing through the streets of Ann Arbor, and bonded, telling each other absolutely everything. Now Sharon lived in Napa Valley with her veterinarian husband, matching chocolate labs, and two little girls. The last time they’d Facetimed, Carolyn told her about Magyar, the new three-star restaurant in SoHo with goulash to die for, and Sharon talked about cute toddler words and what the vet did to her dogs. Carolyn supposed that the veterinarians of California never went unemployed, unlike the graphic designers, campaign workers, key grips, hungry agents and famished actors. Sharon sounded busy, happy in her exhaustion, secure in her sunbathed life.

Carolyn was suddenly routineless, laid off, unpaid, as alone as the loneliest of everyone else. It was if the curtain had crashed down in the middle of the Second Act. People always think plagues won’t come back and every war’s the one that’ll end all wars. But wars and epidemics are like earthquakes and hurricanes; there are always more of them.

More and more often, Carolyn’s mind became unbridled, floating. One dreary afternoon, it drifted to Dürer’s apocalyptic woodcuts she remembered from Art History. The Four Horsemen Ride Again, she whispered. It alarmed her that the words actually came out, that she didn’t just think them. Once, when she was a child, she had seen a man talking to himself and thought he was talking to her. Her mother had pulled her away and whispered that only crazy people talked to themselves. She wondered if we always remember those things our mothers whisper to us.

To Carolyn it was a revelation that you could be scared and bored at the same time. For a while, she thought about that, how, physiologically, it could be possible when being scared makes you alert and quick while boredom makes you dull and languorous. Thinking about her brain and its three parts made her drowsy. So much did. Carolyn worried that she was sleeping too much: a nap in the morning and another in the afternoon, a full nine hours every night. Her schedule had become that of old ladies and infants, opposites that meet on a circle of somnolence.

Like a child who scarfs down a tub of vanilla ice cream and can’t look at the stuff for a decade, Carolyn had had enough of phone calls, Facebook, emails, tweets, people posting upbeat snapshots and desperately cheery videos, dancers collaborating over continents, orchestras playing from bedrooms. One morning she didn’t even boot up then, later, feeling it a momentous act, switched off her I-phone. She didn’t want any more distraction; it felt like evasion. She would keep up with the news on radio, all the news that wasn’t directed just at her.

She missed her mother but hadn’t phoned her in weeks. There wasn’t any point in trying. She felt like a motherless child and hummed the tune.

She put water on for tea, turned on the radio, heard the latest tally. Monty Python. Bring out your dead. She carried her cup of tea to the window, pulled back the curtain and looked down on the lifeless, neutron-bombed street. Everything was the same as yesterday and the day before, even the trash in the gutters.

She lay down on her bed. No need to pull the sheets tight, for hospital corners, to tuck the blanket in; no need to shampoo either, put on makeup, pick out tomorrow’s outfit. She only had to wash her hands, spray doorknobs, mask-up and venture out for food. Shopping had become foraging. The idea of a shopping list now seemed ludicrous. You searched for what you could use in what little was there.

She lay on her back and thought of her sophomore year, the one when she had tried to keep a journal. Perhaps the journal popped into her mind because writing in it was the last time life had seemed so—she struggled for a word—interior. But keeping at the journal was too hard; she was lazy and rationalized that living was better than thinking about living. There were parties, dates, two clubs, homework, exams. She had written in one those expensive Moleskine books, with a narrow black ribbon to mark pages, like a bible. Her father had sent it to her for her eighteenth birthday. That made it five years before he died and nine before her widowed mother married Ben, a nice man with an unfortunate mustache. He had died too and only a year after the quiet wedding.

Carolyn realized now that her father probably intended the notebook as an encouragement, something to make her more reflective. Her father had “Carolyn’s Journal” put on the cover in gold letters. She took it as an assignment and also a criticism. Her father had been a professor of Greek and Roman history, and it disappointed him that she had zero interest in his wars and emperors and was only attracted by the myths, which she called “those old fairy tales.” Still, because she loved her father, she’d forced herself to keep up the journal for a long time, well at least for a few months.

Carolyn found it easy to drop the tiller of her mind, especially when she was supine. Journals are to diaries as films are to movies, she mused, as ships are to boats, hotels to motels. The analogies were her favorite section of the SAT. Journals are to diaries. . .

Feeling a sudden urgency, Carolyn leapt off the bed. She needed to see that journal pronto. Finding it wasn’t a whim but the immediate focus of her day. If she’d saved it, the book would be in one of the cartons down in the storage locker. She threw on her yellow hoodie, her mask, grabbed her keys, opened the door gingerly and made sure the hallway was empty. Then she dashed to the elevator, waited for it, tapping her foot impatiently. When it finally came, she jabbed the BB button.

The sub-basement was humid and there were cockroach corpses against the walls and in the corners. The fluorescent lighting was spotty, flickery. Her locker looked like rubble. It took her half an hour to find the book. What a relief! Though it smelled of mildew and the pages had curled, her handwriting was legible—far clearer than it was now.

She flipped though the book. Ouf, she said out loud. She’d barely covered thirty pages; she hadn’t even kept it up for a whole month.

She closed up the carton, hastily restacked it, and carried the journal back to the elevator, resolved to go through it before lunch.

Most of what she read was embarrassing, the log of a lingering post-adolescence, a chronicle of parties, gossip, whining, callow philosophizing, fleeting enthusiasms, judgments both mean and superficial. What she had written wasn’t a journal at all; it was only a diary. But then she came to the next-to-last entry, the longest in the book and the only one she would not have been ashamed for her father to read.

A red-letter day. Prof. Krasnow and Prof. Washburn both said something memorable at the end of their lectures, nearly a pair of proverbs. Krasnow delivered a survey of utopianism from Plato to Pol Pot. At the end, he said, “No perfect society is good, and no good society is perfect.”

Washburn’s lecture was supposed to be about Heinrich von Kleist’s play, The Prince of Homburg, which I really liked and wanted to learn more about; but, as usual, she wandered far afield. I can’t decide whether her digressions are down to advancing age, intellectual scope or just exuberance. No matter. Before dismissing the class, she turned her Athena-face on us. “Nobility,” she said sternly, “has nothing to do with happiness. Nobility’s an attitude toward unhappiness.”

I agree with Krasnow up to a point. I mean I’m not a fan of totalitarian idealism either. But he’s settled into what looks like a tweedy and self-satisfied middle-age. He’s a bit too comfortable with human imperfection. His thinking’s like a well-upholstered easy chair. Maybe because I’m young what’s imperfect makes me indignant and angry; I feel like protesting, not shrugging. Krasnow likes Aristotle and dislikes Plato and no wonder. I think Aristotle must have been born middle-aged; and, though he’s right about a lot, that’s mostly because his teacher was so much more brilliantly wrong.

As for what Prof. Washburn said about nobility and unhappiness—it’s made me think, though not really about either. It started me thinking about solitude, which is lovely, and loneliness which is a kind of sadness. Maybe the only difference between them is just that one makes you unhappy and the other doesn’t. I think of myself as outgoing and sociable, and yet there have always been times when I’ve yearned to be left alone, all alone, to be free of my parents, cousins, friends, classmates—free of everybody.

Mother phoned tonight about the credit card and said I was ungrateful. I had a fight with Scott yesterday and, for no reason at all, Sharon was snippy with me at dinner.

Solitude sounds like bliss; and yet, I wonder. If it turned into loneliness, could I face it with nobility?

Carolyn closed the book and started to weep. She didn’t mean to. She wept for herself, her father, for Ben and her thrice-bereaved mother who had lost two husbands and then her memory. She no longer remembered that she had a daughter. She wept for the people in the hospitals struggling to breathe and the exhausted nurses trying to keep them alive. She pulled herself together and rubbed away her tears. There’s nothing noble in weeping.

She went to the kitchen and wrapped the journal in tin foil, the way you do leftovers, then stuffed it in a drawer between sweaters.

Years later, when Carolyn had married and had a little boy, when she was a wife and mother and stopped being an orphan, nobody wanted to recall that time, the perilous hiatus of isolation. What with her job and friends, the club and the baby, she was always busy and hardly ever alone.

When Chip got a promotion, and Carolyn was planning a dinner party to celebrate, she remembered a wedding gift, a pair of silver candlesticks that would make her table look more elegant. She had put them away and never used them. They would be in one of the boxes in the basement.

The first carton she opened contained old serving forks and spoons. The second was full of her old sweaters. They made her feel sentimental, nostalgic. She pulled out a gray turtleneck and then smiled at the mauve cardigan that her mother had hated. And there, on top of a white cotton pullover, was the moleskin journal still wrapped up tight, sealed off and put away like a leftover pot roast.

Carolyn unwrapped the journal and remembered the lockdown, her studio apartment, how it felt then. She opened the book, her father’s gift, his assignment, and saw again how little she’d written. She read her criticism of Professor Krasnow’s comfort with imperfection and the tragic words of Professor Washburn. They both felt like a reproof.