The Dead River

Jéanpaul Ferro

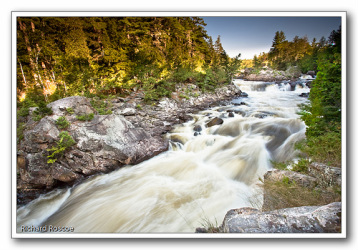

JACK LINTON HAD BEEN FLOATING down the Dead River for three long months now. Early in the morning, the sun would turn the crown of each wave a different hue of golden-brown, turning a flat black as each swell slouched down and became a rapid at Elephant Rock and Mine Field.

The river was ancient compared to a man, and each morning it seemed to get older; but at thirty-eight, Jack felt this enormous power come up within himself, something that he had never felt while he was working his nine-to-five job over the course of the past twenty years. Up in Maine, Jack could become the man he’d always wanted to be—fit and muscular with no one telling him what to do or how to do it.

Northern Maine was a beautiful sphere atop New England. White pines grew down in the valleys and up along the shoulders of the mountains and hills. Blue lakes dotted the landscape with horse-like moose and deer around every green corner.

It had been exactly three months—three months since he had left New London and Pfizer for the calm waters of Jackman, Maine. Three months of floating down the Dead River, the Kennebec, and the Penobscot. Three months of having to drive the old school bus through sylvan tracts of spruce to get down to the dam. Three months of trying to forget her when he could feel her in every second.

Being in Maine made Jack look at things differently now. Being a guide on a river instead of on some soft blue computer screen gave him hope again.

He first noticed it after working at the rafting companies for a couple of weeks. With the constant sun turning his hair the same color as a wheat field back where he grew up in a southern county in the black hills, he noticed that not only did he see himself differently, but everyone else saw him for someone he didn’t know he was.

“You’re a frontiersman!” one woman from Albany told him when they hit the big rapid on the Kennebec and the raft didn’t turn over.

“A real Renaissance man!” a woman from Georgia told him when he cooked steak for forty people one night.

“I wish my husband were like you,” a very sad twenty-something girl from Mississippi said as Jack hung up on a line all the wetsuits for the entire company one night after dinner.

Each time Jack soaked it in, parsed it, moved it around his veins and intestines, knowing he really wasn’t any different than any other man. It felt good having other people, especially women, especially women he would have been interested in, thinking he was someone totally different than the person he really was. This was the feeling that motivated every man. A man wanted power and money and prestige and fame for the same reasons. Wanted to be thought of as someone different and perfect and not as he was in the secret recesses of his mind at night.

The girl had arrived in late September with her husband and another handsome couple who’d bowed out of the rafting trip after the first day on the Dead River. All summer long he had been watching wives like this one.

“I want to sit back by you!” she shouted to him as she climbed into his raft on the last day of the excursion.

Jack nervously looked back at her husband. He had these humored eyes and this bulging fat face and swollen red neck that didn’t seem to match the subtle beauty of his wife. He was laughing with the man from Syracuse as they stood on the big rock beside the raft. The man from Syracuse had come here alone and the husband had adopted him for the weekend.

“He doesn’t care,” Jack heard the woman say half under her breath.

He looked at her. She stood in her blue and yellow wetsuit. She was blond and thin and flat-chested. There was something irresistible about her existence. He could see the pain she wore in her eyes. She was about twenty-six or twenty-seven, with an overconfident gaze, gray eyes, and a mouth always poised and ready to say something original. And she was a firstborn, like he was. He saw it the minute she walked up to him in the lodge and introduced herself. “Helene Thalhofer,” she said as she slipped her hand into his. “My friends all call me Kat.” When she said this he felt as through maybe they had known each other in another life—maybe somewhere on the Delta off in Tanis or on the northern Sinai coast in ancient Egypt.

He looked at her now as she sat in his raft. Her eyes kept surprising him. They were the same color as the Kennebec: blue like when the river flattens out around the corner and catches the last light of day on its surface. Her eyes unnerved him. All the eyes of the other women hadn’t moved him until now.

He helped her husband and the man from Syracuse down into the raft, then the six happy college kids who were up from Northeastern.

It was dark and gray out that morning. It was cold when Jack put on his wetsuit in the tent. There was a mist in the air and some of the leaves on the sugar maple and the yellow birch planted around the camp had already started to turn into their autumn shades of orange and yellow.

Jack took a deep breath as he untied the raft from shore. He pushed off away from the rocks. He straightened out, to maneuver with his paddle. He saw the man from Syracuse paddling the wrong way. “No! No!” Jack shouted over to him. “You’re not Dennis Conner. Do what I told you to do!”

The man looked back. “Sorry. Sorry.”

Quickly, the raft moved out onto the rapids.

Jack shouted the commands he had taught his novice crew back at the lodge.

They moved through the granite canyon and out into the open blue river.

Some days the wind would come up from the north and Jack could smell the bitter decay of the paper mill from up in the hills. But that morning the mist and the clouds blunted the smell from coming down.

The blond woman kept looking back at him instead of paddling. The rapids grew larger and more powerful and everyone was smiling nervously like at a great play or on a roller coaster.

Jack shouted more commands as the water broke and crashed over them. He turned straight on, right for the big twelve-foot rapid they called Magic. He knew he had to hit it straight on or risk turning the raft over.

“Go! Go!” he shouted.

They hit the huge wall of water, sunk down into the blackish-gray gulch, then came up the other side.

Jack felt the wave in his stomach. It felt like the second after kissing a girl for the first time.

He smiled.

“Great! Great!” he was yelling at them. “This is what it’s all about! This is what it’s all about!”

They drifted downriver, passing some of the other raft companies near the waterfall where the Kennebec turns flat and gray.

Jack tried to ignore her now. He didn’t want to embarrass her husband, but she kept trying to talk to him; but this was mean, defensive talk, and he didn’t say anything back to her.

They went ahead downriver for an hour, and then he put them on shore and took the passengers for a walk through the woods to get their legs back. There were woodpeckers and blue jays up on branches in the trees, every branch waving and trembling in the wind, patches of black muddy ground everywhere one stepped. Jack began to pass out some trail mix he had put together the night before—Chex cereal, raisins, walnuts, M&M’s, pecans, and popcorn.

The blonde woman, Kat, trailed behind everyone else. Jack saw her blonde hair matted down and wet and she had color in her cheeks now. The sense of her beauty began to rise up in him and he wanted to feel it.

“This job you have?” she said as everyone drifted ahead of them. “I’d die to have your job. I’m stuck in a room without any windows all day. Some days I don’t even know if the sun’s out.”

“I know,” he said. “Last year I was locked in a room teaching technical writers how to version their documents. A zero-point-a is not the same as a one-point-one.” He saw her turn and look back at him. “It’s not much of a life,” he said. “I just couldn’t do it anymore.”

“I know,” she said, nodding.

He watched her as she stopped in the middle of the trail.

The rest of the group, ahead of them, turned a corner. Jack bumped into the woman. He saw her turn and look up at him.

Her mouth was gentle. He noticed that she stared at him like they had always known each other just like he had thought.

He pretended this was a mistake. He tried to walk around her.

“Don’t you believe in fate?” she said, her voice shaking.

Jack watched her reach out for his hand. He could feel her shivering from being in her wet suit for too long.

“You let water get into your lining,” he told her. He looked into her eyes. “No. I don’t believe in fate. Not anymore.” He thought about it. “I was locked in a room for too many years to believe in fate.”

“I know,” she said. “But I’ve never, all my life…”

He pulled away from her. A wet linden branch brushed against his cheek as he moved back, slightly cutting his face.

He could feel the warmness of the blood as he wiped it away. He touched it and saw some of the blood on his hands. He tried not to look at her. He looked straight ahead for the group, but they were gone.

“What are we going to do?” she said.

“What can we do?”

Jack dropped the bag of trail mix and slumped to the ground like a baseball catcher. His face fell into his hands as the wind picked up and the mist and water dripped down from the canopy of the needles and leaves above them.

He began to think about his mistakes. Twenty years earlier he had loved this girl and he had let her get away. There were reasons. A million reasons and excuses and explanations. His parents wanted one thing for him. Her parents wanted one thing for her. Neither of them wound up with anything. He wanted never to feel like that again. There were all these rules in other peoples’ lives. But what rules were there up in Maine?

Jack watched the woman kneel beside him. He felt her try to put her arms around him, but he pushed back. She leaned into him and forced her warm mouth against his neck, but it lasted only for a second.

And then they could hear the voices of the husband, and the man from Syracuse, and the six happy college kids from Northeastern coming back down the trail toward them.

Jack looked at her, because he knew what he wanted, but he had spent his entire life doing the exact opposite.

He jumped up and cleared his throat.

He saw her hold her hand over her mouth as she stood up. There were tears in her gray eyes.

“There they are!” the husband shouted to the man from Syracuse.

“Come on! We found another waterfall,” one of the college kids shouted. “It’s so beautiful.”

“We’ll be right there,” Jack said. “We’re coming.”

He started to walk toward them and the woman followed behind.

Jack followed the trail that he knew much better now, and he watched the sky through the trees and saw some holes of blue begin to open up. He sensed the slight smell of the paper mill as it began to come up in the air.

He saw the waterfall ahead.

He stopped with the woman just before the end of the trail.

Jack felt her trembling right beside him.

“You’ll find someone else,” he said to her.

He kissed her gently on the forehead. Just as he did he began to feel the same way he always had, and it scared him to feel this, here, too.

He heard everyone shouting for them again, and he could smell the stench of the paper mill begin to grow strong.

Jack and the woman let go of one another. He ran his hand against her cheek. She was different from the others. He knew it. They were just like each other, but then there was all this other make-believe stuff too.

“I’m only a guide on a river,” he said to her. He watched as she closed her eyes and let out a deep breath.

Jack took her hand and gave her a little push. He saw her looking at him, but slowly and deliberately pushed her to walk out in front of him. Together they went over to where the others waited for them, where they Ooh-ed and Aah-ed with everyone else in front of a waterfall that Jack had seen a thousand times before. And neither of them said anything, and they just stood there and pretended just like everyone else.