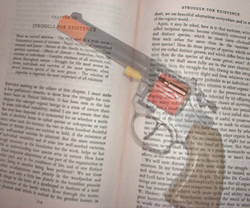

The First Thing an Artist Should Learn

is How to Use a Gun

(excerpt from Orgasmo)

Donald O'Donovan

Yesterday Byron Lovelace, the painter, dropped by. We took the bus downtown. Byron was excited; he’d just sold another copy of the Mona Lisa, but it turned out that there was something else he wanted to talk to me about.

“Guess what,” he began, as we were crossing Bonnie Brae Street, “I’m writing a novel. Does that surprise you?”

“Not at all. Why should it? If you can paint you can write.”

We go to Clifton’s and find an out of the way table. We both get the split pea soup and the cornbread. Byron is bursting with talk about his book.

“Whom The Gods Love! That’s the title. Do you like it?” Without waiting for my reply he goes on: “The hero’s name is Alexander Marquis. That’s one of the pen names you used when you wrote for Bareback Books. Isn’t that right? The truth is, I’ve chosen you as the model for the lead character. He’s a middle-aged writer with a suitcase full of rejected novels, unknown, unpublished, a complete failure. You don’t mind my saying that, do you? It all goes back to something we talked about months ago. At La Golondrina, do you remember? The first thing an artist should learn is how to use a gun. We were sitting on the patio. Do you remember now? Well, that was just a germ, a nucleus. This thing has grown, believe me! My head is seething with ideas. I understand how it is with you guys now, you writers. You get an idea in your head, and you go crazy with it. It takes over your life. Ideas are an obsession, a drug. Not a drug that brings you down, a drug that puts you to sleep, but a snort of pure oxygen—a sort of intellectual cocaine. Do you like that phrase, ‘intellectual cocaine?’ Listen, I’ve got a million of ‘em. The minute I started jotting down ideas for this book I felt something click. Let’s take, for example, my choice of the name for the lead character, Alexander Marquis. It’s perfect, don’t you see? And my other characters: Lloyd Masselin, Karen Mulhern, Tessa Tremaine. I’m finding that I’ve got a knack for that, for choosing character names. This facility of mine—and I hope I don’t appear too self-congratulatory—is something I find lacking in your work, if you don’t mind a shot of criticism from an old friend. For example, your book about Mexico. What was the title? Tarantula Woman? There was that fat girl—the whore who was in love with you. What was her name? Profunda, ah, yes, Profunda. Somehow that didn’t ring true...”

“That was her real name. I didn’t bother to change it because I knew she’d never read the book. She couldn’t read. She was illiterate.”

“Ah, yes. Her real name. I understand now. But it wasn’t ‘real’ real. Know what I mean?”

“No.”

What I like about Clifton’s Cafeteria is that it reminds me of the cafeteria in New York that Isaac Singer describes so beautifully in his books, a place where he and other destitute writers subsisted on bowls of noodles and coffee cake— and conversation. I can almost see him, Isaac Bashevis Singer, sitting a few tables away, a frail but luminous figure, writing in Yiddish, a bowl of noodles at his elbow, his head percolating, now pausing to reflect, now lost in thought, now writing furiously, his electric blue eyes snapping as the words migrate from his head to his fingertips like a swarm of bees.

“Let’s get back to the plot,” Byron is saying. “I think you’ll find this interesting. Alexander Marquis—we’ll call him Alex—has a painter friend, Lloyd Masselin, modeled of course on yours truly. Lloyd counsels Alex. He has a sure-fire scheme, you see, for getting published. The conversation goes something like this: “ ‘Listen to me, Alex. The way to publication is fame. The way to fame is crime. Commit a spectacular crime and you become a world figure. Get media exposure and publication is assured. Get your manuscripts in order, buy a gun with a telescopic sight and grab a plane to Washington—or a taxi to Hollywood. It doesn’t matter whether you kill the President or a princess or a movie star. As long as it’s somebody famous. That’s your ticket, Alex. Publication guaranteed. They’ll probably make a movie about you, too—like they did with Lee Harvey Oswald and Gary Gilmore and Charlie Manson and the Boston Strangler.

The criminal celebrity Caryl Chessman wrote the best seller, Cell 2455, Death Row, while awaiting execution at San Quentin. Did you know that? James Earl Ray, convicted murderer of Martin Luther King, presently pursues a burgeoning literary career from his cell at the River Bend Penitentiary in Nashville. Mark David Chapman, John Lennon’s assassin, signed a book contract shortly after being imprisoned at Attica and even wrote to Yoko Ono to ask that she participate in the venture. Incidentally, Chapman had with him when he shot Lennon outside the Dakota a copy of The Catcher in the Rye—not a bad book, by the way—a circumstance which reaffirms an association I’ve been investigating, the close connection, in modern times, between literature and crime, between literature and murder, and in particular, between literature and assassination.’

“I also want to mention in this context something I unearthed about John Wilkes Booth, Lincoln’s assassin. It seems that Booth gave a sealed letter to the actor John Mathews—to be delivered to the publishers of the National Intelligencer—this on the day of the assassination. The letter, which was never published, since Mathews burned it, explained how Booth had devoted his time, money and energies to arranging President Lincoln’s kidnapping, all without success, and that it was now time to take more definitive action. The delivery of the letter to Mathews was followed by the shooting at the Ford Theater, the flight of John Wilkes Booth to Zekiah Swamp and his demise at the Garret Farmhouse.

“ ‘Well,’ Lloyd Masselin goes on, ‘you see what I’m getting at, Alex, my boy. Put your manuscripts in order, buy yourself a gun, select a famous victim, pull the trigger... You’re made! Beautiful, isn’t it? I imagine they’ll let you go on writing in prison, too—unless you get the chair. Either way, you win.’

“The first thing an artist should learn is how to use a gun. Do you get it now? Do you see how it all ties in? Well, moving along with the plot, Alex decides to take Lloyd’s advice. After all, life is war. He’ll blow some celebrity away in order to pull himself up into the spotlight on the coat tails of a famous corpse. And so the die is cast.

“The rest of the plot is rather elementary. Having decided on a course of action, Alex sets about his work with elaborate precision. He packs his thirteen rejected novels in a steamer trunk and places the trunk in storage. He drafts a ‘Letter of Explanation,’ a document that tells quite candidly why he did what he did, and he dispatches the letter to his attorney along with the key to the storage unit where his manuscripts are held. Accompanying the sealed Letter of Explanation and the key are instructions to his attorney stating that the contents of the sealed envelope are to be released simultaneously to the police and to the press when Alex is arrested or upon notification of his death. Alex’s plan, incidentally, is to assassinate the President of the United States. He buys a folding rifle with a telescopic sight, practices at a range, and makes several trips to Washington for dry runs. In the meantime, he begins a diary—‘The Assassination Diary’—documenting his preparations, his thoughts, his misgivings, his resolutions, and so on. Never before has an assassin provided the world at large with so thorough an examination of his motives, and of the living, thinking mind behind those motives. The Assassination Diary, Alex realizes, is a human document of the utmost importance. He is filled now with a sense of purpose, a sense of destiny. What was it Napoleon said? ‘I feel myself driven towards an end that I do not know. As soon as I shall have reached it, an atom will suffice to shatter me. Till then, not all the forces of mankind can do anything against me.’

“I know I’m doing all the talking,” Byron interrupts himself. “Would you like another bowl of soup? What about some cornbread? I hope I’m not boring you.”

“No, no, no, no...”

“The rest of the plot, as I say, is elementary. After the dry runs and the preparations, comes at last the real thing. Alex flies to Washington for his rendezvous with destiny. He makes his way to the roof of a building that he has previously reconnoitered, a vantage point from which he will have a clear shot at the President’s caravan when it passes, as he has previously ascertained, at three that afternoon. He has with him, in addition to the murder weapon, The Assassination Diary, in which he is madly scribbling. He has made a pact with himself to record his thoughts and actions right up the decisive moment when he squeezes the trigger, and beyond, until he surrenders himself to the arms of the police. As the hour approaches, however, a seemingly unrelated incident transpires. A prostitute and her pimp have also ascended to the roof, and are involved in a violent altercation. The pimp slaps the woman

around. She’s sobbing, and her face is covered in blood. Alex, outraged, rushes to the conflict and tries to protect the woman, and in the process he’s stabbed and fatally wounded by the pimp.

“The pimp and the prostitute rush off, leaving Alex to die. The President’s caravan passes without incident, and Alex bleeds to death on the concrete. As an ironic footnote, at this very moment, Alex’s agent has telephoned to inform him that one of his novels, The Brass Lollypop, has just been accepted for publication.”

Byron pauses for a moment, dangling his spoon over his soup, and for a hallucinating instant I see Isaac Singer with the tablets in his hands and the words shooting like flames from his fingertips.

“Well, what do you think of it? I admit that it’s based, to some extent, on Crime and Punishment. Why not? Raskolnikov killed the old pawnbroker, Lizaveta, to prove that he was a man of action—a Napoleon. But Napoleon doesn’t have to prove he’s Napoleon, don’t you see? Raskolnikov is very much like you and me. He’s not a man of action, and he never will be. He’s a Hitler without charisma. He’s trapped inside the prison of his own mind. He’s a failed artist, an angel without wings. In the end, it’s Sonia, the ‘holy prostitute’ who provides the way to salvation. Inspired by his love for her, Raskolnikov moves out of the arena of the intellect altogether. He enters a new dimension for him—the realm of the spirit. In the same way, my hero, Alexander Marquis, alias you, the failed writer... He has it all planned out, the assassination of the President, but at the last instant, life intervenes. He follows his heart. He moves to rescue the prostitute, a woman who is altogether unworthy of his attentions. But that doesn’t matter, you see. What matters is his action—pure, unselfish...totally extraneous to the program he has set up for himself. And although it costs him his life, this unselfish action on his part, there is a sense of fulfillment, because he has come full circle, from alienation to involvement. Well, what do you...”

What do I think! My Christ! I’m astonished at Byron’s description of his novel. My God, the man’s a genius. A Picasso of literature! Why, I’ve never hatched anything remotely approaching Whom the Gods Love!

But a week went by and then two, and I found myself at Clifton’s once again, thinking about Byron’s novel. A sparkling précis, to be sure, Byron, but will you be able to write it? Haven’t I listened to the dreams of an army corps of would-be writers, talking out their books in a hundred shit-hole bars? Great expectations, yes, but can you sit down at the typewriter and churn it out? Can you sit there hour after hour, until the words are no longer entities in your mind but flames leaping from your fingertips?

As if in answer to my question, in walked Byron, and he was flying high. He’d just sold a copy of Van Gogh’s Starry Night. And the novel? Whom the Gods Love? What about the novel? He mumbled something about needing to do some more research and quickly changed the subject. Then he took his grubby spiral notebook out of his shirt pocket and began thumbing through the pages.

“Check it out,” he burbled, “that’s the third Starry Night this month! And listen to this, Donaldo. My total sales for the year so far are twelve Starry Nights, fifteen Mona Lisas and fourteen Last Suppers…”