Fossilized

Nicole Yurcaba

Coal is a fossilized fuel formed in ecosystems where plant remains were preserved by water and mud from oxidization and biodegradation. Coal towns erupted all through the Appalachian Mountains, and immigrants from Russia, Ireland, the Ukraine, and Italy swarmed to these towns in pursuits of jobs and “The American Dream.”

Among a batch of freshly arrived immigrants to Ellis Island in 1917 was Nicholas Michael Yurcaba. “Yurcaba” is the Americanized form of the Ukrainian name “Yortsaba”. Nicholas Michael Yurcaba would eventually marry Anna Fellon, years later after he’d arrived in Trevorton, a small coal mining town in the Pennsylvania mountains. He would work in the dungeon-like mines, risking life, limb, and the possibility of “black lung” to provide for his family. In 1938, he and Anna would have a son—their only son—whom they would call Nicholas Jerome Yurcaba. Nicholas, who would at age fifty, father a daughter named Nicole Anna-Marie Yurcaba, never worked in the mines. Nicholas would graduate from Trevorton high school, attend St. Vincent’s College in Latrobe, PA. At age 20 he would drop out of college and join the Army, where he served from 1960 to 1962 as a medic. Attending college and joining the US Army would buy his escape ticket from Pennsylvania’s coal fields.

On bleak grey days, Daddy and I would travel to Shamokin Mountain where the mining business still boomed in Trevorton. He would buckle me into the front seat of his silver Chevrolet pick-up truck with maroon cloth interior and step-side bed. We never knew how long we’d be on the mountain, so he’d pack a cooler with Diet Coke, peanut butter sandwiches and Snickers bars. Some mornings we spent hours fossil hunting; I can still remember the excitement of finding a piece of fossilized tree, its imprint clear in the grayish black slate rock. My youthful imagination conjured what colors the tree might have been in dinosaur days. Daddy knew so much about everything—fossils hunting, deer hunting, coal mining. As a little girl I believed no other man in all of God’s creation could ever be as intelligent, as wise or as much fun as my much older father. Daddy relayed Granddaddy’s mining stories—Yurcaba oral histories, I called them in later years—to my young willfully listening ears.

Other mornings, we merely went to get loads of coal for heating purposes. Most every house in Trevorton, since it was readily available, heated with coal. I remember the sweet carbonic twinge of coal dust in young nostrils. A slight burn when I breathed inward; I wondered how much coal dust Granddaddy had inhaled over a thirty year course of mining. His lungs must have been blackened, hardened—similar to the piece of petrified wood I’d discovered while fossil hunting.

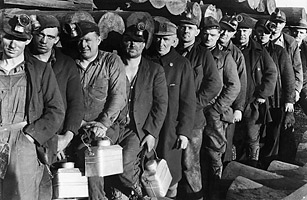

Miners fascinated me: skinny, lanky, cruddy miners wearing dirty headlamps and blackened Dickies overalls. Modern day miners no longer use old carbide lanterns that the old timers, like Granddaddy, used back in their day. (Daddy tells me as a young man, after miners stopped using carbide lanterns for work, he began using them for coon hunting.) White teeth smiled from black faces, and Daddy’s miner friends were always cheerful when we pulled up in our dusty truck before their rickety mining work shack. Never once did they mistake Daddy for being “Pappy” or “Grandpa”, like so many other people, even those who knew us or were at least acquainted with the Yurcaba’s, often did.( Not many folks could believe that he’d sired a third child at age fifty with a gorgeous wife twenty years his junior.) They were most all young fellows whose names I can no longer recall, but at one time I had girlhood crushes on each and of them. My girlish mind imagined a handsome, young, coal dust-covered miner falling head over steel-toed boots in love with me, begging for my soft hand in marriage; I imagined not being a coal miner’s daughter, but instead a coal miners wife. A coal miner’s wife—as Grandma had been for nearly fifty-seven years before Granddaddy passed away from cancer. These childhood daydreams were the closest I ever came to fantasizing about a white wedding. The miners called me “cute”, and whenever I arrived with Daddy they would cheer, “Well, there comes cutie-pie!” They threw crushed beer cans on silty black ground, and cussed with each drawn breath.

“I’m sorry.” one of them would say, taking note that if my childish ears heard no evil, then I would most likely never speak any evil. I think visiting the miners is where I first learned the proper use of foul words such as “hell”, “damn” and the mother of all swears—the “F” word. During summer evenings when my best friend, Alex, and I would make mud pies at the spring below the Trevorton house, known as “The Billabong”, I’d impress her with my newfound knowledge of how to fit swear words into appropriate conversation. The first time I ever said the word “damn” in front of my mother, at about age nine, she looked at me—dumbfounded --and asked “What did you say?” Not only did I cuss, I also wanted to drink beer because the miners drank beer. Daddy didn’t drink the miners’ brand, but I recall him drinking green bottles of Rolling Rock while I was growing up. Hot summer evenings would come hand-in-hand with July and August, and he would send me to the summer porch’s fridge to get him a Rolling Rock. One little hand would hold the condensation-covered bottle tightly; the other little hand’s fingers would work to twist off the aluminum bottle cap. I thought I was being ingenious by only sipping enough of the piss-colored liquid down past the bottleneck’s blue and silver oval-shaped label. I would run on awkwardly long legs down through the backyard grass screaming “DAA-DDYY! HEERRE’S YER BEEEERR!”

“It’s not full. I told you not to be sneaking sips.” Daddy would chastise. I’d look at him, innocently doe-eyed.

“I didn’t. It spilled out when I was runnin’ down the hill.” I’d answer, but he knew. He knew all those years I was sipping his cold, delicious, habit-forming beer. Nowadays he is proud that by age twenty-one, my beer tastes have matured to Yuengling Lager, Yuengling Black and Tan, and Foster’s.

Daddy would park the old Chevy beneath the mining shoot, where with a flick of a switch chunks of coal would rattle down the long steel pathway. When I grew up, became old enough to drive, the Chevy Daddy drove then would become mine the very day I turned sixteen, or so I thought in those days. I would jack it up high in the air and set in on big tires like the truck Mama told me she had before she got pregnant with me—the truck with chrome roll bars, fourteen-inch lift and size forty-four Super Swamp tires. In the front seat, I would sit, anxiously waiting for the familiar low rumble of tumbling coal. My overactive imagination imagined coal being churned and puked from Earth’s fiery stomach into those rickety metal shoots.

Little did a naïve child’s mind know that sometimes down those dark dungeons accidents happened—gases exploded, mine walls collapsed, and at an unknown household between Shamokin and Trevorton, a wife learned that her husband lost his life in the jaws of Shamokin Mountain. Their hardhats would remain, like an organism’s hard outer shell, long after the soft tissue parts of their bodies had decomposed, fill with sediment, hardening , petrified, leaving a cast-like stone replica to be found millions of years later.

Miners seemed invincible to me at such a young age, though Granddaddy had died shortly after I was born due to cancer. I never knew him, never heard his mining tales or witnessed his drunken Friday night bouts after he came home from the Bowery after working, sunup to sundown, in the mines. Black lung, which stole their breath and made them hack up their lungs, killed most of them eventually. Mine walls collapsed, trapping them within Earth’s bowels. Mine gases built up causing unforeseen and random explosions.

Daddy once told me, “The old time miners would take a caged bird down into the mines with them. When they went down in the mine and the bird stopped whistling or singing, they knew they’d gone to where the gases had become poisonous.” Not only is coal the largest world-wide source of fuel for electricity generation, it is also the largest contributor of carbon dioxide emissions.

I never looked at the mines the same way. The mines were no longer a place where we went on Saturday mornings to visit his miner friends and get a few weeks’ worth of coal for the furnace, or pick through old slate rock for ancient fossilized creatures. No, after Daddy’s explanation, the mines became hellish pits where men worked, slaved to retrieve black treasure and nearly lost their lives in grueling, life-threatening processes. Dying for the sake of coal. Compressed between Earth’s foundations until their organic molecules were altered into geochemically altered states, and skeleton-imprints became fossilized stamps. I would sit in the truck’s front seat, tears rolling down my young, smooth but cruddy face, staring through the dusty windshield at huge coal banks and sparsely treed black hills. It took me months to get over the horrific tale of dying birds signaling men like Granddaddy to “Exit! Exit! Hurry! Get out!” Before the coal began to pour into the pick-up bed, I’d demand that Daddy leave the truck radio on, so that I could play my favorite Blackfoot cassette tape over and over with the radio blasting to drown out the deafening rumble of Earth puking coal into the steel shoots and into the pick-up bed. Listening to the cowboy song where the ghost riders came and yelled “Yippee-ki-yay!” and prodding Heaven with their reddened brands was less scary than the hellish mines.

“Why are you crying?” Daddy asked me once. I sobbed harder, wiped my tear-stained face on the sleeve of my oversized sweatshirt.

“It’s s-sc-scary!” I’d wail, babyishly. And he’d shake his ball-capped gray head. Tough girls weren’t supposed to cry, and supposedly I was (and always would be) Daddy’s tough girl. Tough girls didn’t cry when their daddies, on Saturday mornings, took them to Shamokin Mountain for a mine visit.

“You were never scared before.” he’d say, “Why all of a sudden?” I didn’t have the boldness to tell him that his grim story had frightened me. That I hated thinking about little green birds trapped in cages, dying the very instant they encountered a poisonous underground gas. I hated the image of the little bird lying dead in its cage, and a tall lanky, dust-covered miner like Granddaddy realizing all too late that the bird had died and the gases were going to kill him, too, because he hadn’t escaped Earth’s deadly fumes soon enough. Shortly after that, Daddy let me go and fiddle around in the work shack whenever we’d go get a load of coal. And I would sit in at the foreman’s desk and draw him pictures, which he hung next to the fading yellowish, nearly amber- colored pin-ups the young lads had tacked up on dingy wooden walls.

To me, a naïve child, those pin-ups were merely beautiful young women. Maybe one of the miner’s girlfriends? He wanted to brag to his mining coworkers, “I might be nothin’ but a roughneck miner, but look at her, and she’s mine.” Years later, I learned about Playboy and Hustler, what such magazines represented and sold. What an epiphany! The pictures on the work shack’s wall suddenly made complete sense after one afternoon down in the Trevorton home’s dingy mine-like basement. I discovered musty cardboard boxes littered with even mustier copies of Granddaddy’s Playboy collection. He’d saved every issue from the early 1960s well through the 1980s--preserved nicely, pages intact. Photographs, though slightly aged by time, relatively vibrant.

***

Just the other day on 96.9 Real Country I heard Johnny Cash singing, “Come all you young fellows, so young and so fine, and seek not your fortune in a dark dreary mine.” I wondered if the mining shack still sat up on Shamokin Mountain, if the mine was still active and if the once-handsome miners of my youth were still gainfully employed. It has been twelve long years since I visited Trevorton. We moved to West Virginia, back to Mama’s old stomping grounds, and I haven’t been back to old Trevorton since then. Daddy sold the silver Chevrolet-- which I had affectionately nicknamed “The Silver Bullet”-- shortly after we moved back to West Virginia. My childhood best friend, Alex, tells met the Bowery is still open to accommodate town drunks and the local miners who work in the West Cameron mine. Late at night when the Bowery’s closing time is announced, she says you can hear the drunks fighting, using words such as “hell”, “damn” and the mother of all swears—the “F” word.

Had I stayed in Trevorton, graduated from Line Mountain high school, Alex tells me I wouldn’t have had to worry about being the only “Ukie” in a predominantly Irish-descended high school. The immigrants moving into Trevorton—Hispanics, mainly—do not go to work in the few mines that remain open. Instead they pursue janitorial jobs, fast-food service and welfare. The Hispanics, like the numerous Russians, Irish and Ukrainians before them, are striving for the highly cherished and reverent “American Dream”.

If I ever decide to go back to Pennsylvania, I want to take my truck—a grey Dodge Ram 1500, which I sentimentally nicknamed “The Silver Bullet—and ride up onto Shamokin Mountain. I doubt, if any of the miners who worked the Shamokin mine back then, still work there, or if they do, would remember me at all. I want to look at them and ask, “Do you remember Nick Yurcaba’s daughter? The little girl who used to sit in his truck and cry because low rumble of pouring coal scared her? Are the pictures I scribbled as a young’un for the old foreman still hanging by the dirty black-topped desk? What happened to the old foreman? How badly have the pinups aged, yellowed, beiged? And do you by chance know what brand of beer them miners drank?”