Girl on the Balcony

Robert Granader

I watched her die.

Even from my hotel balcony five blocks away, I could tell. Even as the fading sun of the day dipped, its sharp angle blinding me as it hit off the casino’s mirrored facade. I saw her put a leg over the rail and then the other and then she was gone.

I couldn’t do anything from my perch or in my condition.

Even if she did jump, it wasn’t much of a jump, more like a step over the edge, and then I heard people yelling.

I did get up from my chair, squinting to get a better view. But I soon sat down and was back at my newspaper. What could I do but wonder why?

During business trips like this, I don’t get to the newspaper until late in the day. The nights are long and the mornings slow.

I asked the guys at the hotel whether they had heard about the jumper.

“Did you see her jump?” one of them asked.

“No.”

“Did you hear her fall?” another said. “It’s a horrible sound.”

“How many bodies have you seen fall?” someone asked my interrogator.

“Well, none,” he admitted.

“Great story, you saw nothing and heard nothing,” another said.

“It’s not up for debate,” I told these drunk idiots. “It’s like going to bed with a clean driveway and waking up with a snow-covered lawn. I can assume it snowed, even though I didn’t see the flakes coming down.”

“I didn’t see nothing on the news,” Gretna chimed in from behind the bar. “Maybe they waitin’ on tellin’ the family.”

“Why did she do it?” Bobby, the most sentimental of the men at the bar that night, asked. “I mean how bad was it?”

It’s impossible to know what’s in somebody’s head, of course, but I told them when I saw her standing just beyond the railing, I could tell by the angle of her face that she was going over.

“What the hell does that mean?”

“She paused,” I said, “and just looked down, resigned to her fate. As if she had no choice. It was like somebody was sticking a gun in her back. But there wasn’t anybody there, nobody giving her a push. Just the demons in her head that must have followed her around every day of her life.”

“And I suppose you saw those demons from your balcony?”

“No, but they’re there,” I fought back.

It was after two in the morning, and the bar was closing by the time we began fighting about this. There will be time to fight about it again, or something else, the following night.

I couldn’t stop thinking about the girl when I got back up to my room after another night in another hotel bar with these men I’ve know for fifty years. Guys I grew up with and whom I see when I come back to town three times a year. I say I’m here for business, but I just miss the bar. Drinking alone at home is hard.

I couldn’t tell them this, but I could see her demons; they were all over her. And some of them were mine. I know they were there. An old drunk once told me about his demons. And I recognized them too. Like the ones I tried to outrun by leaving town. But they followed me to all those jobs in all those towns and into all those bars. They crash into my head without knocking. The ones who spend their time flying around my thoughts.

“You can’t deny them,” he said. “Not with drink, not with nothing.”

But then he told me how to just live with them: “Since they are gonna be there, you might as well make friends with them,” he said. “Bring out some tea and enjoy their company.”

I told him I’d bring out the gin.

But not everybody can. Not everybody has tea or can afford gin. Not everybody can afford the advice of a man in a bar at 3 a.m. And so the demons float around our heads, and we don’t know that we can do something with them other than be tormented by them. We don’t realize there is another way. And finally, after so much time, the demons dominate our heads and we wind up dead.

We no longer recognize ourselves. We look in the mirror and see only demons, and that’s what happened to the poor girl on the roof.

At night, when she turned off the lights or looked up to the stars or her dark ceiling, and all she saw were demons looking back at her.

“Did a girl die here last night?” I ask a short, balding man at the front desk of the building where I think it happened. Earlier in the day I stood, bloody-eyed, on my balcony with my toast and jam and counted the buildings and the streets.

The clerk looked around and nodded to a group of young people in their twenties, crying and consoling each other in the corner.

“I saw her,” I told him before settling into the quiet so we could hear the chatter of the others.

“Why didn’t you do anything?” one of the twenty-something men/boys asked another one.

“What did you say to her?” one of the girls/women said to one of the men.

“I wanted to help,” another said.

“You were the last to see her,” another said.

I was the last to see her, I thought.

“I wanted to see how I could help,” I told the front desk man. But I knew there was nothing to do.

“Maybe you could have helped yesterday,” he said.

I retreated to a café just off the lobby behind the front desk and sat with a coffee I didn’t want.

Why did she do it? How bad was it? They all kept asking each other as if they didn’t know her.

No one ever taught her how to deal with the demons, how to talk to them, how to distinguish between what the demons say and what they are telling you. These demons speak a different language.

The young group continued chatting and laying blame. They talked about someone and something about a fight. They asked why he couldn’t have waited to break up with her. “You knew she was vulnerable.”

When it got quiet I left my coffee cold, with more questions than answers, and sidled back up to the front desk clerk.

“Who’s that?” I asked, nodding toward two sets of crying adults.

“Her parents,” he said.

In one love seat was a middle-aged couple holding each other. The man’s head was shiny and bald; the woman, more hair but a slightly more up-to-date outfit. In the other chair a man with salt-and-pepper hair and a woman about the same age. The inside positions were occupied by people who I later learned were the parents. Each engaged with their new spouse, their knees touching the person with whom they had made a child.

“Always about the food, you had to talk about food,” the man said.

“She wanted to talk about it,” the wife said, wiping her nose. “But she struggled, she just struggled.”

They think it was their fault? They think it was the other one’s fault.

“Humans are built to see the future,” the front desk man said when the lobby cleared.

“What?” I asked, startled by this sudden utterance. Until then it was mostly nods and grunts.

“We are built to see the future and fear it,” he went on. “There was a time when if we didn’t learn how to see the future, we wouldn’t recognize the danger, and we’d be eaten by dinosaurs. Slaughtered by the thing we would have recognized had we learned the language, recognized the signs, separated the animals from the plants.”

There was a picture of a woman tacked up in the lobby. It was the woman. The jumper. The daughter. The friend. Seeing her up close now for the first time, she looked like my cousin Molly. My cousin was so pretty when we were growing up. Only a few years older than I, I had a mad crush on her. In the way that one could as the younger one but with the recognition that it would never lead to anything, never be returned because, in her eyes, I was just a punk. There was safety in that.

When you are kids, younger is younger; it’s a subgrouping, it’s the kids’ table, it’s like being in a separate fishbowl. You can’t get there from here.

But that was before life made her face puffy, her stomach bulge, and her back hunch. Her first husband caused the lines because he was mean when he drank, which was a lot. And her second husband caused the bulge because he was just mean all the time. And the kids. Oh, the kids, they caused the hunch as they carried them through life. She tried to reverse it with the meds, and then the shots and the Botox and the makeup, until finally her face was an unrecognizable yin and yang.

Age pulled her eyes down, and the shots pushed them up.

Age puffed her cheeks out, and the medicine sucked them back in.

And so this woman whose picture now hangs on the lobby wall reminded me of Molly before the fall. This girl’s face was pretty. It would never be deformed by age. And for that fleeting moment, when I watched her from afar, I wondered how she got there. Logistically.

Usually the rooftop of an apartment building is hard to get to, except in movies.

Turns out she didn’t live there, which makes her escape to the roof even more improbable, impressive. I heard one of the earlier lobby gatherings talking, and their theory was that she was a guest at a party, and she wandered up there looking for the bathroom.

But the guy at the front desk shook his head. He’d heard there was shouting. She was embarrassed or someone broke up with her, and she’d had enough and decided she needed some air, and then, once up there, she took the opportunity.

“She regretted it,” he said.

“How do you know?”

“Suicide survivors, you know, the ones who try but don’t die. Almost one hundred percent of them say as soon as they step off the bridge, they regret it. Falling through the air, they all wished it were a bungee cord that would pull them back up.”

But was this woman being chased by her demons or was it more opportunistic?

Like getting divorced. Everybody thinks about it at some point. As one longtime couple said, “We both wanted a divorce but, thankfully, never at the same time.”

Never that moment where opportunity meets the moment. Maybe she never wanted to kill herself, but after a bad night, had the opportunity opened up?

As the sun sank into Lake Pontchartrain, she found herself on that rooftop with this demon on her shoulder, or the boy who broke up with her, or the father who picked on her, or the friend who didn’t stick up for her. It wasn’t one thing. It wasn’t one of them now crying in the lobby. It was all of them. And so she took that small step over the rail and left it all behind.

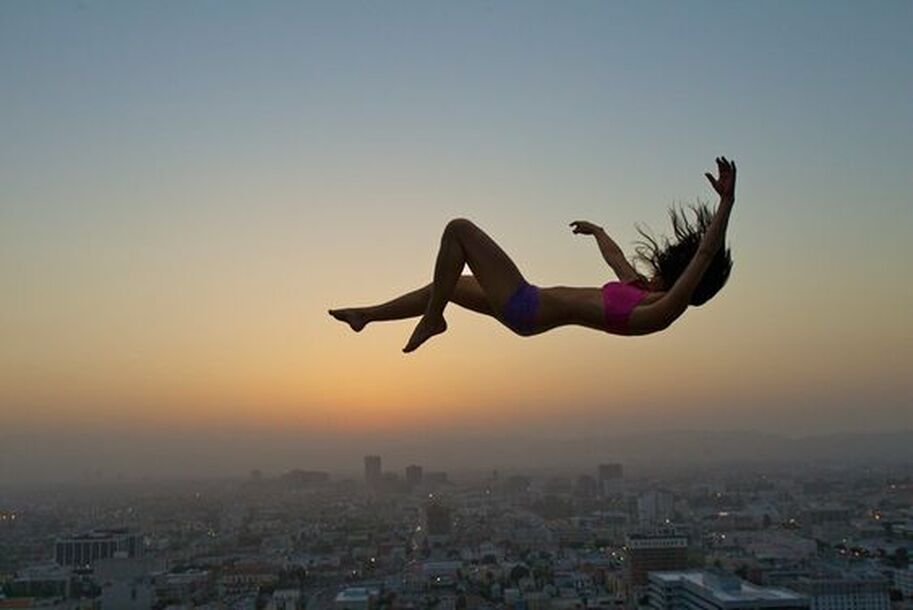

She was silent as she turned her body, midair, from feet first to head first, as if she was completing a hands-free dive into a warm infinity pool. But instead of waiting for the warm water to welcome her in, it was the cold, hard cement that crushed her skull and broke her neck, I imagine.

But there was no body.

People said they saw a body going down.

I saw a body stepping over the side.

My new front desk friend said he spoke to the papers, and there were others like me who said they saw a woman on the roof of the sixteen-story building.

But when the reporters dug deeper and asked if they saw her jump, no one could say for sure.

When they checked with the hospital, there was no patient with a crushed everything.

When witnesses were rounded up, they said, “She must have.” And I said, she must have.

The sign over the picture in the lobby just said MISSING.

In the evenings I go down to the hotel bar to drink with my friends until I feel I am ready for sleep. Sometimes it takes longer than others. They say alcohol is the wrong way to do it, but I don’t know of any other way to quiet the world in a way that lets me rest.

When I feel the demons have all flown away or at least had a drink with me, I go out on my balcony and watch the lights through the cigarette smoke, and I look for the girl they never found.

Each night I’m out there, I watch for her and hope maybe this time I can stop her. The pretty girl who climbed over the railing, the girl who did not jump but disappeared from her life and her family and her problems without ever having to endure the pain. I look for her on streets and in the bars; I long to see the face I never met. I want to teach her how to talk to demons, not just drown them out with gin or crush them from sixteen stories up.

I want to tell her it will be okay.

Robert Granader

I watched her die.

Even from my hotel balcony five blocks away, I could tell. Even as the fading sun of the day dipped, its sharp angle blinding me as it hit off the casino’s mirrored facade. I saw her put a leg over the rail and then the other and then she was gone.

I couldn’t do anything from my perch or in my condition.

Even if she did jump, it wasn’t much of a jump, more like a step over the edge, and then I heard people yelling.

I did get up from my chair, squinting to get a better view. But I soon sat down and was back at my newspaper. What could I do but wonder why?

During business trips like this, I don’t get to the newspaper until late in the day. The nights are long and the mornings slow.

I asked the guys at the hotel whether they had heard about the jumper.

“Did you see her jump?” one of them asked.

“No.”

“Did you hear her fall?” another said. “It’s a horrible sound.”

“How many bodies have you seen fall?” someone asked my interrogator.

“Well, none,” he admitted.

“Great story, you saw nothing and heard nothing,” another said.

“It’s not up for debate,” I told these drunk idiots. “It’s like going to bed with a clean driveway and waking up with a snow-covered lawn. I can assume it snowed, even though I didn’t see the flakes coming down.”

“I didn’t see nothing on the news,” Gretna chimed in from behind the bar. “Maybe they waitin’ on tellin’ the family.”

“Why did she do it?” Bobby, the most sentimental of the men at the bar that night, asked. “I mean how bad was it?”

It’s impossible to know what’s in somebody’s head, of course, but I told them when I saw her standing just beyond the railing, I could tell by the angle of her face that she was going over.

“What the hell does that mean?”

“She paused,” I said, “and just looked down, resigned to her fate. As if she had no choice. It was like somebody was sticking a gun in her back. But there wasn’t anybody there, nobody giving her a push. Just the demons in her head that must have followed her around every day of her life.”

“And I suppose you saw those demons from your balcony?”

“No, but they’re there,” I fought back.

It was after two in the morning, and the bar was closing by the time we began fighting about this. There will be time to fight about it again, or something else, the following night.

I couldn’t stop thinking about the girl when I got back up to my room after another night in another hotel bar with these men I’ve know for fifty years. Guys I grew up with and whom I see when I come back to town three times a year. I say I’m here for business, but I just miss the bar. Drinking alone at home is hard.

I couldn’t tell them this, but I could see her demons; they were all over her. And some of them were mine. I know they were there. An old drunk once told me about his demons. And I recognized them too. Like the ones I tried to outrun by leaving town. But they followed me to all those jobs in all those towns and into all those bars. They crash into my head without knocking. The ones who spend their time flying around my thoughts.

“You can’t deny them,” he said. “Not with drink, not with nothing.”

But then he told me how to just live with them: “Since they are gonna be there, you might as well make friends with them,” he said. “Bring out some tea and enjoy their company.”

I told him I’d bring out the gin.

But not everybody can. Not everybody has tea or can afford gin. Not everybody can afford the advice of a man in a bar at 3 a.m. And so the demons float around our heads, and we don’t know that we can do something with them other than be tormented by them. We don’t realize there is another way. And finally, after so much time, the demons dominate our heads and we wind up dead.

We no longer recognize ourselves. We look in the mirror and see only demons, and that’s what happened to the poor girl on the roof.

At night, when she turned off the lights or looked up to the stars or her dark ceiling, and all she saw were demons looking back at her.

“Did a girl die here last night?” I ask a short, balding man at the front desk of the building where I think it happened. Earlier in the day I stood, bloody-eyed, on my balcony with my toast and jam and counted the buildings and the streets.

The clerk looked around and nodded to a group of young people in their twenties, crying and consoling each other in the corner.

“I saw her,” I told him before settling into the quiet so we could hear the chatter of the others.

“Why didn’t you do anything?” one of the twenty-something men/boys asked another one.

“What did you say to her?” one of the girls/women said to one of the men.

“I wanted to help,” another said.

“You were the last to see her,” another said.

I was the last to see her, I thought.

“I wanted to see how I could help,” I told the front desk man. But I knew there was nothing to do.

“Maybe you could have helped yesterday,” he said.

I retreated to a café just off the lobby behind the front desk and sat with a coffee I didn’t want.

Why did she do it? How bad was it? They all kept asking each other as if they didn’t know her.

No one ever taught her how to deal with the demons, how to talk to them, how to distinguish between what the demons say and what they are telling you. These demons speak a different language.

The young group continued chatting and laying blame. They talked about someone and something about a fight. They asked why he couldn’t have waited to break up with her. “You knew she was vulnerable.”

When it got quiet I left my coffee cold, with more questions than answers, and sidled back up to the front desk clerk.

“Who’s that?” I asked, nodding toward two sets of crying adults.

“Her parents,” he said.

In one love seat was a middle-aged couple holding each other. The man’s head was shiny and bald; the woman, more hair but a slightly more up-to-date outfit. In the other chair a man with salt-and-pepper hair and a woman about the same age. The inside positions were occupied by people who I later learned were the parents. Each engaged with their new spouse, their knees touching the person with whom they had made a child.

“Always about the food, you had to talk about food,” the man said.

“She wanted to talk about it,” the wife said, wiping her nose. “But she struggled, she just struggled.”

They think it was their fault? They think it was the other one’s fault.

“Humans are built to see the future,” the front desk man said when the lobby cleared.

“What?” I asked, startled by this sudden utterance. Until then it was mostly nods and grunts.

“We are built to see the future and fear it,” he went on. “There was a time when if we didn’t learn how to see the future, we wouldn’t recognize the danger, and we’d be eaten by dinosaurs. Slaughtered by the thing we would have recognized had we learned the language, recognized the signs, separated the animals from the plants.”

There was a picture of a woman tacked up in the lobby. It was the woman. The jumper. The daughter. The friend. Seeing her up close now for the first time, she looked like my cousin Molly. My cousin was so pretty when we were growing up. Only a few years older than I, I had a mad crush on her. In the way that one could as the younger one but with the recognition that it would never lead to anything, never be returned because, in her eyes, I was just a punk. There was safety in that.

When you are kids, younger is younger; it’s a subgrouping, it’s the kids’ table, it’s like being in a separate fishbowl. You can’t get there from here.

But that was before life made her face puffy, her stomach bulge, and her back hunch. Her first husband caused the lines because he was mean when he drank, which was a lot. And her second husband caused the bulge because he was just mean all the time. And the kids. Oh, the kids, they caused the hunch as they carried them through life. She tried to reverse it with the meds, and then the shots and the Botox and the makeup, until finally her face was an unrecognizable yin and yang.

Age pulled her eyes down, and the shots pushed them up.

Age puffed her cheeks out, and the medicine sucked them back in.

And so this woman whose picture now hangs on the lobby wall reminded me of Molly before the fall. This girl’s face was pretty. It would never be deformed by age. And for that fleeting moment, when I watched her from afar, I wondered how she got there. Logistically.

Usually the rooftop of an apartment building is hard to get to, except in movies.

Turns out she didn’t live there, which makes her escape to the roof even more improbable, impressive. I heard one of the earlier lobby gatherings talking, and their theory was that she was a guest at a party, and she wandered up there looking for the bathroom.

But the guy at the front desk shook his head. He’d heard there was shouting. She was embarrassed or someone broke up with her, and she’d had enough and decided she needed some air, and then, once up there, she took the opportunity.

“She regretted it,” he said.

“How do you know?”

“Suicide survivors, you know, the ones who try but don’t die. Almost one hundred percent of them say as soon as they step off the bridge, they regret it. Falling through the air, they all wished it were a bungee cord that would pull them back up.”

But was this woman being chased by her demons or was it more opportunistic?

Like getting divorced. Everybody thinks about it at some point. As one longtime couple said, “We both wanted a divorce but, thankfully, never at the same time.”

Never that moment where opportunity meets the moment. Maybe she never wanted to kill herself, but after a bad night, had the opportunity opened up?

As the sun sank into Lake Pontchartrain, she found herself on that rooftop with this demon on her shoulder, or the boy who broke up with her, or the father who picked on her, or the friend who didn’t stick up for her. It wasn’t one thing. It wasn’t one of them now crying in the lobby. It was all of them. And so she took that small step over the rail and left it all behind.

She was silent as she turned her body, midair, from feet first to head first, as if she was completing a hands-free dive into a warm infinity pool. But instead of waiting for the warm water to welcome her in, it was the cold, hard cement that crushed her skull and broke her neck, I imagine.

But there was no body.

People said they saw a body going down.

I saw a body stepping over the side.

My new front desk friend said he spoke to the papers, and there were others like me who said they saw a woman on the roof of the sixteen-story building.

But when the reporters dug deeper and asked if they saw her jump, no one could say for sure.

When they checked with the hospital, there was no patient with a crushed everything.

When witnesses were rounded up, they said, “She must have.” And I said, she must have.

The sign over the picture in the lobby just said MISSING.

In the evenings I go down to the hotel bar to drink with my friends until I feel I am ready for sleep. Sometimes it takes longer than others. They say alcohol is the wrong way to do it, but I don’t know of any other way to quiet the world in a way that lets me rest.

When I feel the demons have all flown away or at least had a drink with me, I go out on my balcony and watch the lights through the cigarette smoke, and I look for the girl they never found.

Each night I’m out there, I watch for her and hope maybe this time I can stop her. The pretty girl who climbed over the railing, the girl who did not jump but disappeared from her life and her family and her problems without ever having to endure the pain. I look for her on streets and in the bars; I long to see the face I never met. I want to teach her how to talk to demons, not just drown them out with gin or crush them from sixteen stories up.

I want to tell her it will be okay.