Bingo Man

David Howard

On the day I was fired from the small radio station in Maine the station manager said, “We’re going in a different direction,” but I knew it was because I was 58 years old and losing my voice.

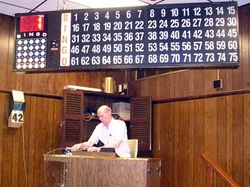

Now I was standing in a Bingo hall at Pleasure Beach in Rhode Island, my voice cracking like a scratched vinyl LP. There were no meters to watch the volume of your voice rise and fall, bouncing with each inflection, only a small microphone in front of me.

“Welcome to Shoreline Bingo,” I said, clearing my throat. “We have 15 great games this afternoon. If you need cards, raise your hand and the beautiful Tina will bring you some.”

I reached for the water bottle. The local newspaper reporter who interviewed me two days ago was standing in the back, next to Jack, the manager. The machine raised the ping pong balls in a blast of air. “G-55” I called into the microphone. “G-55.”

“Can’t hear,” said a voice to his left. “Can’t hear ya.”

“B-9. The number is B-9” I said louder, trying to get a rhythm, pulling the ball after the soft woosh-thunk of it being forced through the hole. Tina, on her round trip of the room peddling cards placed a wrapped hard candy on the table next to the machine, giving me a smile.

Jack gave me the hurry up sign from the back of the room.

“I want to do a ‘where are they now’ sort of story,” the reporter, still a kid, probably his first job, had said as we sat at one of the empty tables in the hall, the smells of fry-o-later oil and popcorn wafting in from the shops next door.

I thought about how I’d been heard late at night by thousands of people whose radio was their only friend. Now I was calling bingo, my voice fading with every number called.

Of course he asked what I was doing here and I told him the same thing I had told myself when I couldn’t get another radio job -- how great it was to be in Pleasure Beach. That calling Bingo was my entry into the world of entertainment for the elderly, and the days of the disk jockey were going the same way as those of the newspaper reporter, he should pay attention to that. “Radio’s a lot different, now,” I’d said, not adding that of course, that I was, too.

“My father told me he used to listen to you on WABC in New York,” the reporter said when he’d finished with his questions and stood up to leave. I thanked him for his time and said. “ABC is all syndicated talk shows now, not a DJ in the place.”

The relief caller, early today, stood beside the manager, a toothpick in his mouth, watching Tina.

“G-48,” my voice sounded like a whisper. I felt more than heard the rumbling from the audience, mostly old people nothing else to do on a weekday afternoon a few days after the Social Security check comes in. “Can’t hear!” they shouted. “Speak up!”

Maybe it was a just a cold. A week of this seemed a lot harder then reading copy and playing music. But now I was at a place where I used to run record hops, climbing the ladder with many of the groups I introduced.

Jack was at the edge of the stage. “What’s wrong with your voice? Christ, get this thing moving.”

I ignored him and pulled a ball, holding it to the light to see the stenciled number. “I-23,” it read and now my voice was suddenly clear and strong, like in New York, Cleveland, Denver, the top rated morning guy.

“Bingo!” someone shouted and I saw the relief guy coming toward the stage, touching Tina as he passed, making her frown. Jack, still there said, “Take the rest of the day off and come in early tomorrow to see me.” He picked up the candy Tina had left, unwrapped it, put it in his mouth and walked away.

Now I was standing in a Bingo hall at Pleasure Beach in Rhode Island, my voice cracking like a scratched vinyl LP. There were no meters to watch the volume of your voice rise and fall, bouncing with each inflection, only a small microphone in front of me.

“Welcome to Shoreline Bingo,” I said, clearing my throat. “We have 15 great games this afternoon. If you need cards, raise your hand and the beautiful Tina will bring you some.”

I reached for the water bottle. The local newspaper reporter who interviewed me two days ago was standing in the back, next to Jack, the manager. The machine raised the ping pong balls in a blast of air. “G-55” I called into the microphone. “G-55.”

“Can’t hear,” said a voice to his left. “Can’t hear ya.”

“B-9. The number is B-9” I said louder, trying to get a rhythm, pulling the ball after the soft woosh-thunk of it being forced through the hole. Tina, on her round trip of the room peddling cards placed a wrapped hard candy on the table next to the machine, giving me a smile.

Jack gave me the hurry up sign from the back of the room.

“I want to do a ‘where are they now’ sort of story,” the reporter, still a kid, probably his first job, had said as we sat at one of the empty tables in the hall, the smells of fry-o-later oil and popcorn wafting in from the shops next door.

I thought about how I’d been heard late at night by thousands of people whose radio was their only friend. Now I was calling bingo, my voice fading with every number called.

Of course he asked what I was doing here and I told him the same thing I had told myself when I couldn’t get another radio job -- how great it was to be in Pleasure Beach. That calling Bingo was my entry into the world of entertainment for the elderly, and the days of the disk jockey were going the same way as those of the newspaper reporter, he should pay attention to that. “Radio’s a lot different, now,” I’d said, not adding that of course, that I was, too.

“My father told me he used to listen to you on WABC in New York,” the reporter said when he’d finished with his questions and stood up to leave. I thanked him for his time and said. “ABC is all syndicated talk shows now, not a DJ in the place.”

The relief caller, early today, stood beside the manager, a toothpick in his mouth, watching Tina.

“G-48,” my voice sounded like a whisper. I felt more than heard the rumbling from the audience, mostly old people nothing else to do on a weekday afternoon a few days after the Social Security check comes in. “Can’t hear!” they shouted. “Speak up!”

Maybe it was a just a cold. A week of this seemed a lot harder then reading copy and playing music. But now I was at a place where I used to run record hops, climbing the ladder with many of the groups I introduced.

Jack was at the edge of the stage. “What’s wrong with your voice? Christ, get this thing moving.”

I ignored him and pulled a ball, holding it to the light to see the stenciled number. “I-23,” it read and now my voice was suddenly clear and strong, like in New York, Cleveland, Denver, the top rated morning guy.

“Bingo!” someone shouted and I saw the relief guy coming toward the stage, touching Tina as he passed, making her frown. Jack, still there said, “Take the rest of the day off and come in early tomorrow to see me.” He picked up the candy Tina had left, unwrapped it, put it in his mouth and walked away.