Horoscopes Don't Lie

Israela Margalit

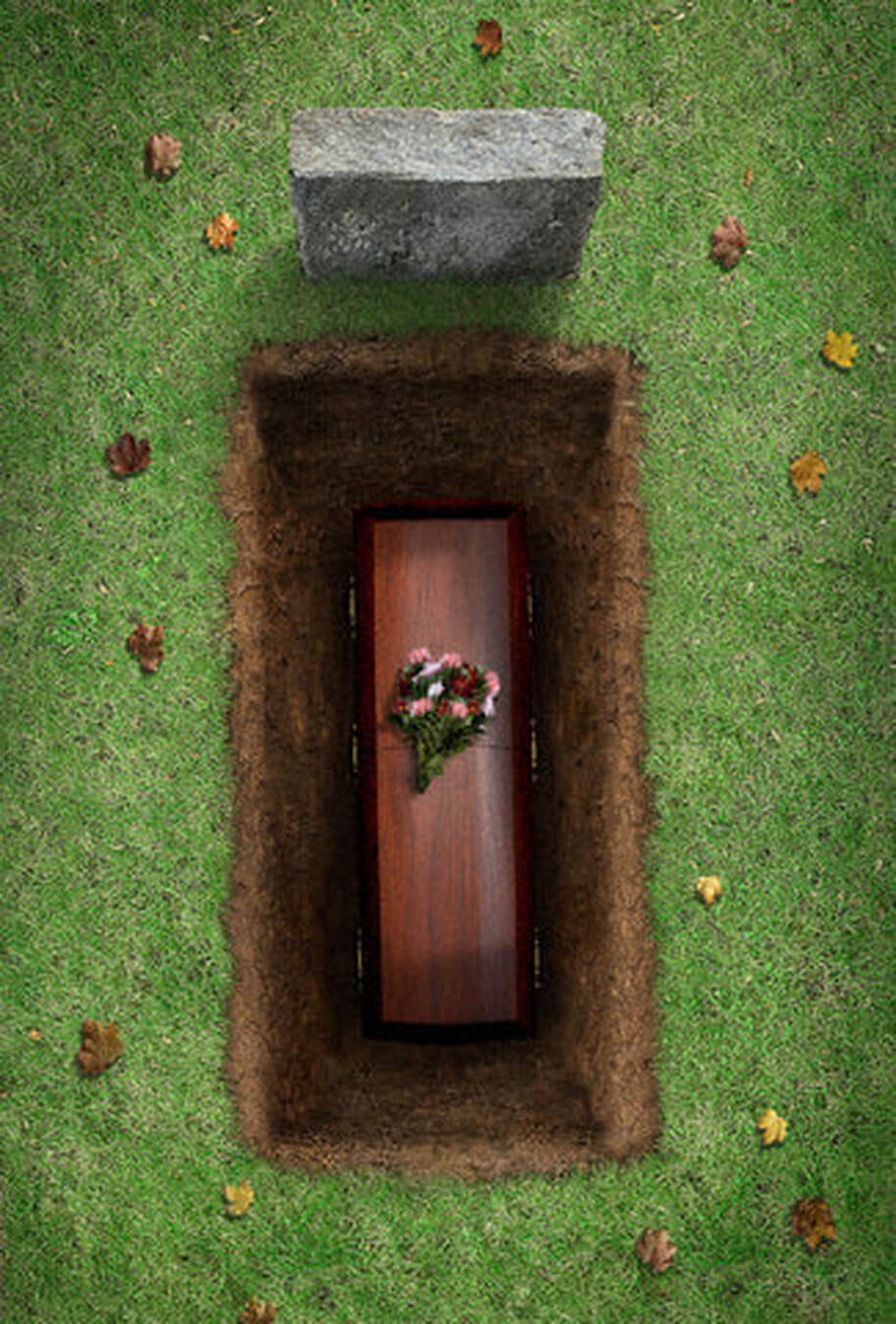

Men in large-brimmed black hats have lowered my mother into a hole. Soon it will be filled with a mixture of sand and gravel. It’s that thick pile next to the hole. The color isn’t right. There’s too much dirt and not enough gravel. The rabbi says there are regulations and measurements that have been established for generations. That much gravel for that much weight. That much dirt for that much gravel. His old skin shines with perspiration and his black coat is wrinkled. My mother wouldn’t have consented to be buried by him. She would have selected a rabbi who looked like young Richard Gere. I wish I could have had some influence over the casting, but by the time my plane landed in Tel-Aviv all the arrangements had been made by Ginger. “Apple lives in New York, so what does she know?”

I’m here with my children. They’re holding my arms and their eyes are moist. My mother was an exemplary grandmother. She conveyed to my kids the value of motivation rather than ambition, and preached fun with no purpose. With her daughters everything had a purpose and life revolved around events. Events that could catch the neighbors’ attention. School plays. Sports meets. Public appearances. When I became a young adult and received my first honor I confronted her.

“Mom,” I said, “for years you’ve been aspiring for this moment. Now that it has arrived will you finally relax?”

She looked at me with astonishment. “I’ll never relax. As soon as this ceremony is over I’ll begin dreaming of your next award.”

I’m trying not to cry. In her youth my mother marched on the sands of Jaffa with banners calling for the exclusive use of the newly revived Hebrew language, and now a group of sweating men are burying her in Yiddish. The language of exile. I don’t understand a word they’re saying except for the “amen” that caps every cadence. It’s my punishment for being a casual Jew. My mother didn’t think that Jewish manifestation mattered as much as Jewish values. What are Jewish values anyway? Family, friendship, country, guilt—universal values except for guilt which is an exclusively national trait.

The rabbi is muttering the last prayer, then he picks up the shovel, fills it with dirt and throws it on my mother. He hands the shovel over to her son-in-law, who covers her with some more dirt. One by one the males in attendance fill the hole until it’s level with the ground around it. The pile is just right, neither too big nor too small. I wish they’d buried her inside an air-conditioned casket, but a casket burial is not allowed by Orthodox Jewish law. Instead they wrapped her in a clothe and buried her naked, all shrouded in white. “Thou shall return unto the ground.”

They asked me to identify her before the procession, to make sure they were about to bury the right woman in the right grave. The burial spot is important. My mother is a sucker for views. She’d enter into life-long debt for a piece of blue sky and a hint of a sunset from her terrace. From this burial spot she can see the mountains. The view is peaceful and majestic.

As firstborn Ginger was asked to identify the body but she declined. I volunteered. I figured I loved my mother enough to see her dead, but then I wished I’d declined too. They raised the white clothe and revealed her face. It looked like one of her pieces of sculpture before she smoothed the plaster. Her mouth was open. Her skin was hard and she wasn’t smiling. She always smiled when she saw me. I confirmed that it was she and signed the death certificate. They covered her face tightly with the white clothe and put a blanket over her. She loved to wear white, even though it made her look heavier. “I’m Jewish; I eat; I’m plump,” she used to say. She carried her body with grace, and when she danced at family weddings she seemed lighter on her feet than any of the size-six young girls with their long legs. White suited her complexion. She wore her white dress every New Year’s Eve and every Passover, and each time she came to the port to meet me. Those were my favorite moments because I had her all to myself and she’d say that I looked pretty without immediately adding that Ginger and Blessing were pretty too. Not that they weren’t pretty. Ginger was good-looking, and Blessing was simply gorgeous. I didn’t mind having pretty sisters, I just disliked it when my mother jumbled our looks together. I wanted her to tell me that I was pretty, then talk about something else. If she would only leave space between the comments, so that I could be the only pretty child for five minutes. But my mother was an equalizer through and through.

“Ginger is good at sports but Blessing shines in basketball. And Apple can run fast.”

“Blessing is brilliant in math but Ginger excels in history. And Apple draws so well.”

She matched our charms and our achievements as much as she could—stretching here, camouflaging there, exaggerating and fantasizing when needed—but for all her efforts she couldn’t equalize the results. One of us grew like a flower in tropical climate while another turned out confused and the third one became aflame with envy. My mother tried to explain away the discrepancies, which she dismissed with a confident smile: “If not today—tomorrow. The horoscopes of Ginger and Blessing are very promising.”

After she had a stroke I asked her if she wanted me to read her the horoscope. She nodded.

“Shall I read you Ginger’s?” I asked. I asked. She frowned.

“Blessing’s?” She frowned again.

“Shall I read you your horoscope, Mom?” She smiled. I read her the prediction from the newspaper. It said she would recover soon and go back home. She smiled. Horoscopes and fortune cookies never lie. Somewhere a woman born under the sign of Libra recovered and went back home, but it wasn’t my mother.

Ginger is making a speech, reading it from a crumpled piece of paper. She’s eulogizing my mother by talking about herself. She’s telling about hours of heart-to-heart conversation with my mother. Hers were not conversations but monologues. Long monologues. Ginger can never get to the matter at hand without describing every detail. Who wore what. What material. How much it cost. Then who said what, in what tone, with what gestures. Then the phone interruption after which she’ll describe how she got rid of the interruption with what words, in what tone, and with what gestures, and how she felt about the phone interruption in what words, and in what tone, and with what gestures. And then the repetition of the beginning lest she’d forgotten something. By the time she gets to the essence of the story, her interlocutor has long stopped listening. But not my mother. She listened to every word with intensity and waited patiently until——some three hours later, Ginger would reach the point of the story and say, “So you understand what happened?” whereupon she would offer to repeat any portion of the story that required more clarification. At the end she always solicited my mother’s advice, and wrote it down in detail on a small piece of paper. Her house is filled with thousands and thousands of tiny little while sheets covered with neatly written instructions in round letters. Her handwriting hasn’t altered with time, and her letters at forty are identical to those she wrote at twenty. Her husband is holding her hand and shedding tears. My mother lent an ear to his grievances against Ginger for as long as they’ve been married, and now that she’s gone he’s left with no one to talk to. I like him because he’s crying over my mother’s death, even if he’s really crying for himself. We all cry for ourselves. Why cry for my mother? She was happy, even when she shouldn’t have been. She had accidental encounters with negativity but didn’t let them last for more than a few minutes at a time. Then she’d grin and say “Tra-la-la-la-la-la-la, the bad stuff came in through one ear and went out through the other.” Tragedy over. That drove me up the wall when I was a teenager and my life evolved around Mahlerian drama.

“How can you act like that, Mom?”

She laughed. “When you’re sad you overeat,” she said. “Your tragedies won’t be real until they make you lose your appetite.”

That never happened to her. She grieved for my father but didn’t stop eating. She surely would have lost her appetite if anything had happened to one of her daughters, but somehow our horoscopes spared us from irreversible bad fortune. Everything that took place in our lives wasn’t monumental enough. Not Blessing losing her mind, not my divorce, not Ginger getting fired. “As long as they’re pretty and talented everything is bound to fall into place.”

Ginger continues to talk with her boomy voice. My mother doesn’t like loud voices. She speaks with the voice of a baby swallow. After her stroke she was taken to the nearby hospital for evaluation where she was placed in a huge room among dozens of other women recovering from strokes of varying severity.

In that hospital—provided you hadn’t died within a week of the stroke—the doctors had to decide whether to transfer the patients to a rehabilitation clinic or to the hospice, and to that end they sent over Maggie, the physiotherapist. A transfer to the hospice was a sure ticket to the morgue while treatment in a rehab clinic gave you a second chance at life, but unless you got recommended you couldn’t get admitted for love or money. So I approached the buxom Maggie and put on my nicest smile for her, the supreme arbiter of my mother’s fate.

“My mother is doing well, Maggie,” I said. “We’ve just had a long conversation and she spoke in full sentences.”

Maggie looked at me suspiciously.

“That doesn’t count. Your mother has got to talk to the nurses. She hasn’t uttered a word in their presence.”

I explained that my mother was a proud woman, that finding herself in the hospital was a scary experience for her. Maggie listened impassively and muttered, “We’ll see.” Then she turned to my mother and screamed:

“Good morning, Mrs. Evergreen. How are we feeling today?”

My mother gave her one look and pinched her lips together like a four-year-old child refusing to eat his cereal. Maggie lifted the blanket off my mother in one fell swoop and shouted:

“Now Mrs. Evergreen, let’s see how those reflexes are working. Come on, come on. Show me how we lift our right knee.”

My mother didn’t stir a muscle. I stood behind Maggie and jerked my thumb to the right. My mother didn’t acknowledge the gesture. So I mouthed “Bibi.” Bibi Netanyahu, the right-wing prime minister, was her favorite. That produced the desired results. My mother smiled and looked at her right knee. Maggie nodded with satisfaction and yelled, “Good girl, we know which side is right! Now lets bend that right knee, shall we? One, two, three!”

Her voice reverberated in the hall, piercing through the moans and sighs of the other patients. “One, two, three! Lets see what we can do, Mrs. Evergreen.”

My mother’s upper lip covered the lower one as she stared at Maggie with defiance. Maggie turned around.

“Your mother doesn’t understand a word I say,” she screamed at me.

I protested that it was not true, and that my mother had just responded to all my questions, but Maggie insisted that it was nothing more than a reflex.

“She repeats what she hears. That gives her the IQ of a parrot.”

She added that since my mother didn’t follow instructions she couldn’t possibly recommend her for rehabilitation.

I hated Maggie. Why couldn’t she say that my mother’s brain was intact? So what if half her brain was damaged? The other half could have sufficed; she was smarter than most people. I went back to my mother. Her lips were parted and she gave me a faint smile. Then she bent her right knee. I thought that it was a good sign, that she wasn’t all that sick. But soon after she got worse; she could no longer bend her knee on command and her painful deterioration began.

It’s Blessing’s turn. She’s prepared a speech. Three-page long. I look at her and wonder why Mom had named her Blessing. If you counted her blessings you wouldn’t even need one whole hand. Her two sons. Two Blessings. Her beauty. A blessing and a curse. It helped her get jobs and lose them. It stopped her from acquiring other tools for living such as wisdom and the art of the non-seductive smile. I haven’t prepared a eulogy and I don’t know what I’d say. I can’t talk about my Mom and her three daughters. We already have Chekhov’s Three Sisters, The Sisters Rosenzweig, Crimes of the Heart, King Lear. Three sisters and an equalizing mother borders on plagiarism. Maybe I could tell the assembly what my mother said to me the last time I saw her before her stroke? She said that she had hoped for more. I couldn’t believe that she would say that.

I was visiting her for two weeks, time shared with my sisters and the extended family. I told her that I wanted to spend the last day with her alone, just the two of us. I expected her to protest and equalize as usual, but instead she agreed.

It was a special day, as if we had known in advance that it would be our last time before the stroke. Just my mother and I. We went to the cemetery to put flowers on my father’s grave. We had lunch in a restaurant. We looked at family albums. We told stories and laughed. She even admitted that she had lured my father away from another woman and immediately denied it. Then she suddenly said she had hoped for more. I knew she was referring to Ginger and Blessing. For a split second I was the only daughter and she shared that confidence with me alone. Then she cheered up and embarked on her habitual glorification of her progeny. My mother was the soul of pride. She’d rather die than admit to a failure.

I can’t possibly divulge her secret and taint her image with the truth, not even over her grave.

Blessing is speaking from the heart with style and clarity, her voice rich and throaty. She’s reading from Elizabeth Browning. It’s a lovely poem and everybody thinks that Blessing wrote it. She doesn’t give Browning credit. Later she’ll explain that Elizabeth Browning had stolen from her, so she was just paying her back.

She used to be so beautiful. It was well known in our family that when Moses led the Jews out of Egypt he took Blessing along, and when the Red Sea saw her, it parted. She used to drive men to distraction. Some of them are here, gazing at the deep black circles under her eyes and wondering what has happened. She’s sharing heartfelt thoughts. How she hoped to have my mother for many more years. How sad it is that God has taken her away. She’s the first person who mentions God in Hebrew. I’m glad she’s not saying that we’d murdered my mother and that the whole thing is a conspiracy. She used to come to the hospice, lift my mother’s blanket and check out her thinning legs, then yell that we were starving her to death. I stopped giving advance notice about my visits. I’d sneak into the country early in the morning, shower and breakfast at my girlfriend’s apartment, then take a cab to the hospice. By the time my sisters found out I was there, I had already stolen away a few private hours with my mother. The fourth time I came my mother recognized me. Her eyes lit with joy; she grabbed my hand and didn’t let go. I sat beside her and told her about the family. I asked her many questions about her care and how she was feeling, but she didn’t answer. After lunch I sat down on a chair by her bed and fell into the deepest sleep. When I woke up her face was turned in my direction and she said, “I feel well.” A full sentence. The patient in the other bed was amazed.

“She hasn’t said a word in months,” she marveled.

I said to my mother, “I love you,” hoping she’d say, “I love you too.” She smiled and said, “I feel well.”

“I love you” was not part of her vocabulary and it was too late to learn new words.

I desperately wanted to please her.

“Mom, I got remarried and I won a big award,” I said.

She smiled.

“Shall I tell you about the wedding or the award?” I asked.

“The award,” she answered.

I told her about the award and then I took out a picture of my father at twenty-six, his head covered with a beret, holding a pipe, looking dashing. My mother grinned from ear to ear.

“He was handsome,” I said. “Handsome like who, Mom?”

“Like Tyron Power,” she said, almost triumphantly.

She did remember something on her own. The nurses gathered around the bed to witness the miracle of Mrs. Evergreen talking. But that was that. My mother sank into fogginess and didn’t say one more word throughout my visit.

If I could only restore her brain so we could fight about politics and she could tell me that Ginger and Blessing were pretty.

But that wasn’t to be. She never said another word. I knew what she would have liked to say: “Take care of Blessing.” That’s what my father said to me on the day before his fatal heart attack. “Take care of Blessing.”

Blessing has finished her eulogy. My mother doesn’t want anyone to know that Blessing needs my help. Blessing is stunning and gifted, one of the three glorious Evergreen girls. I’m telling the assembly how met a gentleman who told me about a woman on the flight from Tel-Aviv to New York, who didn’t stop praising her three daughters. “That was my mother,” I said. It must have been my mother.

Thank you Mom for giving me an education.

Thank you Mom for teaching me how to appreciate beauty.

Thank you for being my mom.

When I finish the rabbi mumbles something and the funeral is over. Everybody puts a stone on the pile of dirt and Ginger and I walk away, the rest of the mourners following. Blessing lingers behind and I can see her hair shining gold in the bright sun as it did when she was a little girl.

Israela Margalit

Men in large-brimmed black hats have lowered my mother into a hole. Soon it will be filled with a mixture of sand and gravel. It’s that thick pile next to the hole. The color isn’t right. There’s too much dirt and not enough gravel. The rabbi says there are regulations and measurements that have been established for generations. That much gravel for that much weight. That much dirt for that much gravel. His old skin shines with perspiration and his black coat is wrinkled. My mother wouldn’t have consented to be buried by him. She would have selected a rabbi who looked like young Richard Gere. I wish I could have had some influence over the casting, but by the time my plane landed in Tel-Aviv all the arrangements had been made by Ginger. “Apple lives in New York, so what does she know?”

I’m here with my children. They’re holding my arms and their eyes are moist. My mother was an exemplary grandmother. She conveyed to my kids the value of motivation rather than ambition, and preached fun with no purpose. With her daughters everything had a purpose and life revolved around events. Events that could catch the neighbors’ attention. School plays. Sports meets. Public appearances. When I became a young adult and received my first honor I confronted her.

“Mom,” I said, “for years you’ve been aspiring for this moment. Now that it has arrived will you finally relax?”

She looked at me with astonishment. “I’ll never relax. As soon as this ceremony is over I’ll begin dreaming of your next award.”

I’m trying not to cry. In her youth my mother marched on the sands of Jaffa with banners calling for the exclusive use of the newly revived Hebrew language, and now a group of sweating men are burying her in Yiddish. The language of exile. I don’t understand a word they’re saying except for the “amen” that caps every cadence. It’s my punishment for being a casual Jew. My mother didn’t think that Jewish manifestation mattered as much as Jewish values. What are Jewish values anyway? Family, friendship, country, guilt—universal values except for guilt which is an exclusively national trait.

The rabbi is muttering the last prayer, then he picks up the shovel, fills it with dirt and throws it on my mother. He hands the shovel over to her son-in-law, who covers her with some more dirt. One by one the males in attendance fill the hole until it’s level with the ground around it. The pile is just right, neither too big nor too small. I wish they’d buried her inside an air-conditioned casket, but a casket burial is not allowed by Orthodox Jewish law. Instead they wrapped her in a clothe and buried her naked, all shrouded in white. “Thou shall return unto the ground.”

They asked me to identify her before the procession, to make sure they were about to bury the right woman in the right grave. The burial spot is important. My mother is a sucker for views. She’d enter into life-long debt for a piece of blue sky and a hint of a sunset from her terrace. From this burial spot she can see the mountains. The view is peaceful and majestic.

As firstborn Ginger was asked to identify the body but she declined. I volunteered. I figured I loved my mother enough to see her dead, but then I wished I’d declined too. They raised the white clothe and revealed her face. It looked like one of her pieces of sculpture before she smoothed the plaster. Her mouth was open. Her skin was hard and she wasn’t smiling. She always smiled when she saw me. I confirmed that it was she and signed the death certificate. They covered her face tightly with the white clothe and put a blanket over her. She loved to wear white, even though it made her look heavier. “I’m Jewish; I eat; I’m plump,” she used to say. She carried her body with grace, and when she danced at family weddings she seemed lighter on her feet than any of the size-six young girls with their long legs. White suited her complexion. She wore her white dress every New Year’s Eve and every Passover, and each time she came to the port to meet me. Those were my favorite moments because I had her all to myself and she’d say that I looked pretty without immediately adding that Ginger and Blessing were pretty too. Not that they weren’t pretty. Ginger was good-looking, and Blessing was simply gorgeous. I didn’t mind having pretty sisters, I just disliked it when my mother jumbled our looks together. I wanted her to tell me that I was pretty, then talk about something else. If she would only leave space between the comments, so that I could be the only pretty child for five minutes. But my mother was an equalizer through and through.

“Ginger is good at sports but Blessing shines in basketball. And Apple can run fast.”

“Blessing is brilliant in math but Ginger excels in history. And Apple draws so well.”

She matched our charms and our achievements as much as she could—stretching here, camouflaging there, exaggerating and fantasizing when needed—but for all her efforts she couldn’t equalize the results. One of us grew like a flower in tropical climate while another turned out confused and the third one became aflame with envy. My mother tried to explain away the discrepancies, which she dismissed with a confident smile: “If not today—tomorrow. The horoscopes of Ginger and Blessing are very promising.”

After she had a stroke I asked her if she wanted me to read her the horoscope. She nodded.

“Shall I read you Ginger’s?” I asked. I asked. She frowned.

“Blessing’s?” She frowned again.

“Shall I read you your horoscope, Mom?” She smiled. I read her the prediction from the newspaper. It said she would recover soon and go back home. She smiled. Horoscopes and fortune cookies never lie. Somewhere a woman born under the sign of Libra recovered and went back home, but it wasn’t my mother.

Ginger is making a speech, reading it from a crumpled piece of paper. She’s eulogizing my mother by talking about herself. She’s telling about hours of heart-to-heart conversation with my mother. Hers were not conversations but monologues. Long monologues. Ginger can never get to the matter at hand without describing every detail. Who wore what. What material. How much it cost. Then who said what, in what tone, with what gestures. Then the phone interruption after which she’ll describe how she got rid of the interruption with what words, in what tone, and with what gestures, and how she felt about the phone interruption in what words, and in what tone, and with what gestures. And then the repetition of the beginning lest she’d forgotten something. By the time she gets to the essence of the story, her interlocutor has long stopped listening. But not my mother. She listened to every word with intensity and waited patiently until——some three hours later, Ginger would reach the point of the story and say, “So you understand what happened?” whereupon she would offer to repeat any portion of the story that required more clarification. At the end she always solicited my mother’s advice, and wrote it down in detail on a small piece of paper. Her house is filled with thousands and thousands of tiny little while sheets covered with neatly written instructions in round letters. Her handwriting hasn’t altered with time, and her letters at forty are identical to those she wrote at twenty. Her husband is holding her hand and shedding tears. My mother lent an ear to his grievances against Ginger for as long as they’ve been married, and now that she’s gone he’s left with no one to talk to. I like him because he’s crying over my mother’s death, even if he’s really crying for himself. We all cry for ourselves. Why cry for my mother? She was happy, even when she shouldn’t have been. She had accidental encounters with negativity but didn’t let them last for more than a few minutes at a time. Then she’d grin and say “Tra-la-la-la-la-la-la, the bad stuff came in through one ear and went out through the other.” Tragedy over. That drove me up the wall when I was a teenager and my life evolved around Mahlerian drama.

“How can you act like that, Mom?”

She laughed. “When you’re sad you overeat,” she said. “Your tragedies won’t be real until they make you lose your appetite.”

That never happened to her. She grieved for my father but didn’t stop eating. She surely would have lost her appetite if anything had happened to one of her daughters, but somehow our horoscopes spared us from irreversible bad fortune. Everything that took place in our lives wasn’t monumental enough. Not Blessing losing her mind, not my divorce, not Ginger getting fired. “As long as they’re pretty and talented everything is bound to fall into place.”

Ginger continues to talk with her boomy voice. My mother doesn’t like loud voices. She speaks with the voice of a baby swallow. After her stroke she was taken to the nearby hospital for evaluation where she was placed in a huge room among dozens of other women recovering from strokes of varying severity.

In that hospital—provided you hadn’t died within a week of the stroke—the doctors had to decide whether to transfer the patients to a rehabilitation clinic or to the hospice, and to that end they sent over Maggie, the physiotherapist. A transfer to the hospice was a sure ticket to the morgue while treatment in a rehab clinic gave you a second chance at life, but unless you got recommended you couldn’t get admitted for love or money. So I approached the buxom Maggie and put on my nicest smile for her, the supreme arbiter of my mother’s fate.

“My mother is doing well, Maggie,” I said. “We’ve just had a long conversation and she spoke in full sentences.”

Maggie looked at me suspiciously.

“That doesn’t count. Your mother has got to talk to the nurses. She hasn’t uttered a word in their presence.”

I explained that my mother was a proud woman, that finding herself in the hospital was a scary experience for her. Maggie listened impassively and muttered, “We’ll see.” Then she turned to my mother and screamed:

“Good morning, Mrs. Evergreen. How are we feeling today?”

My mother gave her one look and pinched her lips together like a four-year-old child refusing to eat his cereal. Maggie lifted the blanket off my mother in one fell swoop and shouted:

“Now Mrs. Evergreen, let’s see how those reflexes are working. Come on, come on. Show me how we lift our right knee.”

My mother didn’t stir a muscle. I stood behind Maggie and jerked my thumb to the right. My mother didn’t acknowledge the gesture. So I mouthed “Bibi.” Bibi Netanyahu, the right-wing prime minister, was her favorite. That produced the desired results. My mother smiled and looked at her right knee. Maggie nodded with satisfaction and yelled, “Good girl, we know which side is right! Now lets bend that right knee, shall we? One, two, three!”

Her voice reverberated in the hall, piercing through the moans and sighs of the other patients. “One, two, three! Lets see what we can do, Mrs. Evergreen.”

My mother’s upper lip covered the lower one as she stared at Maggie with defiance. Maggie turned around.

“Your mother doesn’t understand a word I say,” she screamed at me.

I protested that it was not true, and that my mother had just responded to all my questions, but Maggie insisted that it was nothing more than a reflex.

“She repeats what she hears. That gives her the IQ of a parrot.”

She added that since my mother didn’t follow instructions she couldn’t possibly recommend her for rehabilitation.

I hated Maggie. Why couldn’t she say that my mother’s brain was intact? So what if half her brain was damaged? The other half could have sufficed; she was smarter than most people. I went back to my mother. Her lips were parted and she gave me a faint smile. Then she bent her right knee. I thought that it was a good sign, that she wasn’t all that sick. But soon after she got worse; she could no longer bend her knee on command and her painful deterioration began.

It’s Blessing’s turn. She’s prepared a speech. Three-page long. I look at her and wonder why Mom had named her Blessing. If you counted her blessings you wouldn’t even need one whole hand. Her two sons. Two Blessings. Her beauty. A blessing and a curse. It helped her get jobs and lose them. It stopped her from acquiring other tools for living such as wisdom and the art of the non-seductive smile. I haven’t prepared a eulogy and I don’t know what I’d say. I can’t talk about my Mom and her three daughters. We already have Chekhov’s Three Sisters, The Sisters Rosenzweig, Crimes of the Heart, King Lear. Three sisters and an equalizing mother borders on plagiarism. Maybe I could tell the assembly what my mother said to me the last time I saw her before her stroke? She said that she had hoped for more. I couldn’t believe that she would say that.

I was visiting her for two weeks, time shared with my sisters and the extended family. I told her that I wanted to spend the last day with her alone, just the two of us. I expected her to protest and equalize as usual, but instead she agreed.

It was a special day, as if we had known in advance that it would be our last time before the stroke. Just my mother and I. We went to the cemetery to put flowers on my father’s grave. We had lunch in a restaurant. We looked at family albums. We told stories and laughed. She even admitted that she had lured my father away from another woman and immediately denied it. Then she suddenly said she had hoped for more. I knew she was referring to Ginger and Blessing. For a split second I was the only daughter and she shared that confidence with me alone. Then she cheered up and embarked on her habitual glorification of her progeny. My mother was the soul of pride. She’d rather die than admit to a failure.

I can’t possibly divulge her secret and taint her image with the truth, not even over her grave.

Blessing is speaking from the heart with style and clarity, her voice rich and throaty. She’s reading from Elizabeth Browning. It’s a lovely poem and everybody thinks that Blessing wrote it. She doesn’t give Browning credit. Later she’ll explain that Elizabeth Browning had stolen from her, so she was just paying her back.

She used to be so beautiful. It was well known in our family that when Moses led the Jews out of Egypt he took Blessing along, and when the Red Sea saw her, it parted. She used to drive men to distraction. Some of them are here, gazing at the deep black circles under her eyes and wondering what has happened. She’s sharing heartfelt thoughts. How she hoped to have my mother for many more years. How sad it is that God has taken her away. She’s the first person who mentions God in Hebrew. I’m glad she’s not saying that we’d murdered my mother and that the whole thing is a conspiracy. She used to come to the hospice, lift my mother’s blanket and check out her thinning legs, then yell that we were starving her to death. I stopped giving advance notice about my visits. I’d sneak into the country early in the morning, shower and breakfast at my girlfriend’s apartment, then take a cab to the hospice. By the time my sisters found out I was there, I had already stolen away a few private hours with my mother. The fourth time I came my mother recognized me. Her eyes lit with joy; she grabbed my hand and didn’t let go. I sat beside her and told her about the family. I asked her many questions about her care and how she was feeling, but she didn’t answer. After lunch I sat down on a chair by her bed and fell into the deepest sleep. When I woke up her face was turned in my direction and she said, “I feel well.” A full sentence. The patient in the other bed was amazed.

“She hasn’t said a word in months,” she marveled.

I said to my mother, “I love you,” hoping she’d say, “I love you too.” She smiled and said, “I feel well.”

“I love you” was not part of her vocabulary and it was too late to learn new words.

I desperately wanted to please her.

“Mom, I got remarried and I won a big award,” I said.

She smiled.

“Shall I tell you about the wedding or the award?” I asked.

“The award,” she answered.

I told her about the award and then I took out a picture of my father at twenty-six, his head covered with a beret, holding a pipe, looking dashing. My mother grinned from ear to ear.

“He was handsome,” I said. “Handsome like who, Mom?”

“Like Tyron Power,” she said, almost triumphantly.

She did remember something on her own. The nurses gathered around the bed to witness the miracle of Mrs. Evergreen talking. But that was that. My mother sank into fogginess and didn’t say one more word throughout my visit.

If I could only restore her brain so we could fight about politics and she could tell me that Ginger and Blessing were pretty.

But that wasn’t to be. She never said another word. I knew what she would have liked to say: “Take care of Blessing.” That’s what my father said to me on the day before his fatal heart attack. “Take care of Blessing.”

Blessing has finished her eulogy. My mother doesn’t want anyone to know that Blessing needs my help. Blessing is stunning and gifted, one of the three glorious Evergreen girls. I’m telling the assembly how met a gentleman who told me about a woman on the flight from Tel-Aviv to New York, who didn’t stop praising her three daughters. “That was my mother,” I said. It must have been my mother.

Thank you Mom for giving me an education.

Thank you Mom for teaching me how to appreciate beauty.

Thank you for being my mom.

When I finish the rabbi mumbles something and the funeral is over. Everybody puts a stone on the pile of dirt and Ginger and I walk away, the rest of the mourners following. Blessing lingers behind and I can see her hair shining gold in the bright sun as it did when she was a little girl.