His Book

Richard Krause

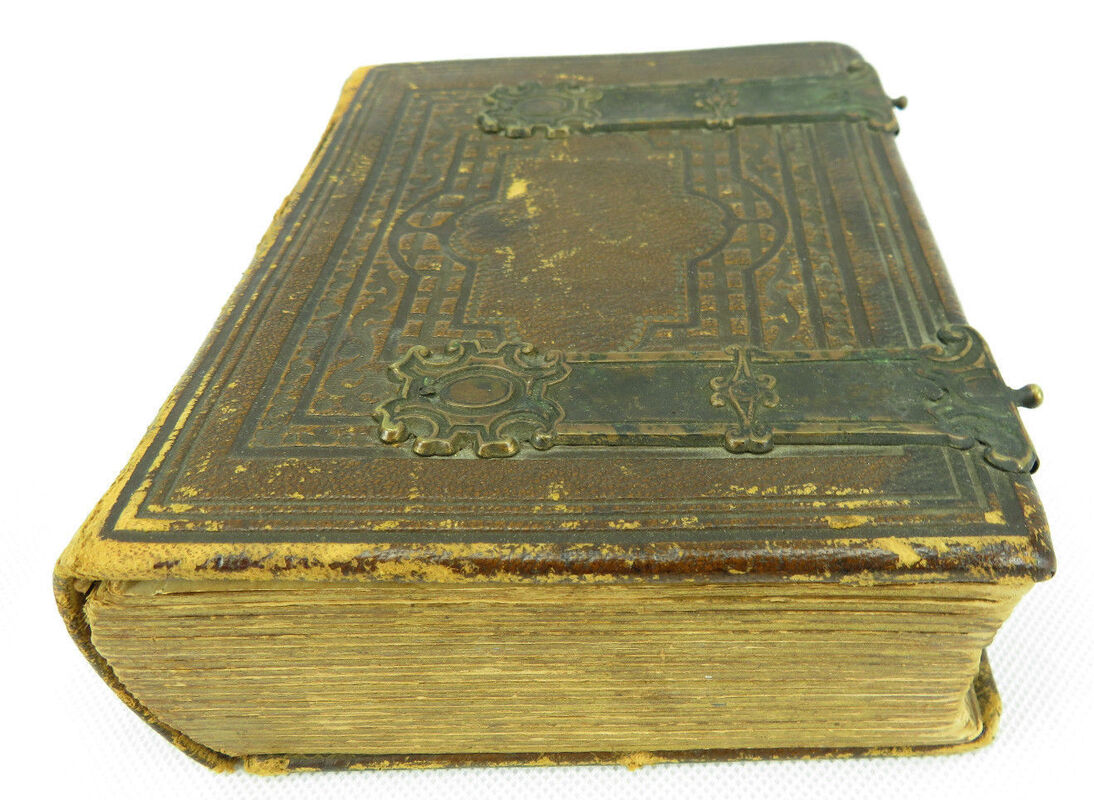

He told me he was writing a book. And one day he showed it to me. I was in it, he said, as were other people we knew, though for the most part the pictures were from magazines, for he wandered the streets collecting them as he begged for money for his long since deceased son who had been severely retarded and confined to a wheelchair. For a stone memorial for him, he told shop owners as he showed them the photo and asked for donations.

"His book" was a very neat album of assorted pictures. One taken of me as I graduated high school; another a bustlike pose of me looking into the future with blue sky and wisps of tiny clouds behind for background. And on the other pages there were pictures of people neither of us knew, but they were pasted in the album for the thousand words they were equivalent to; one of the pictures I had taken in Ireland of a man and his dog coming down a road in Donegal embowered on all sides by lush green scenery. The photograph like many of the rest was a xeroxed copy in black and white, so the imagination could fill in the coloring. There were also a few suggestive pictures from girlie magazines, of cemeteries, of children playing, of art work, marble statues, of workmen from all walks of life, of spokes of sunlight between the trestles of a bridge, all to give an impression of a narrative beyond the visual, highlighting a story that the pictures by their very unrelation to each other could tell. And the few prose selections, sayings, Chinese proverbs, that friends had given him or he had cut out of the newspaper were also there neatly pasted and under plastic, but for the most part they bore no relation to the pictures, though the verbal connections might have suggested some enrichment of plot that the mind would have to struggle for.

The fact too that he could barely read might have added to the format and weighted the pages in favor of pictures—so neatly were they placed and with such care—and also his illiteracy might have contributed to the fact that he called what he was showing me his “novel," even though as he said, it wasn't "finished yet," to quickly insure the inappropriateness of any criticism I might have.

Funny how I could see him one day destroying his “novel" in a rage after a brief glimpse of insight that even if he could read would not have afforded him quite the same clarity.

Richard Krause

He told me he was writing a book. And one day he showed it to me. I was in it, he said, as were other people we knew, though for the most part the pictures were from magazines, for he wandered the streets collecting them as he begged for money for his long since deceased son who had been severely retarded and confined to a wheelchair. For a stone memorial for him, he told shop owners as he showed them the photo and asked for donations.

"His book" was a very neat album of assorted pictures. One taken of me as I graduated high school; another a bustlike pose of me looking into the future with blue sky and wisps of tiny clouds behind for background. And on the other pages there were pictures of people neither of us knew, but they were pasted in the album for the thousand words they were equivalent to; one of the pictures I had taken in Ireland of a man and his dog coming down a road in Donegal embowered on all sides by lush green scenery. The photograph like many of the rest was a xeroxed copy in black and white, so the imagination could fill in the coloring. There were also a few suggestive pictures from girlie magazines, of cemeteries, of children playing, of art work, marble statues, of workmen from all walks of life, of spokes of sunlight between the trestles of a bridge, all to give an impression of a narrative beyond the visual, highlighting a story that the pictures by their very unrelation to each other could tell. And the few prose selections, sayings, Chinese proverbs, that friends had given him or he had cut out of the newspaper were also there neatly pasted and under plastic, but for the most part they bore no relation to the pictures, though the verbal connections might have suggested some enrichment of plot that the mind would have to struggle for.

The fact too that he could barely read might have added to the format and weighted the pages in favor of pictures—so neatly were they placed and with such care—and also his illiteracy might have contributed to the fact that he called what he was showing me his “novel," even though as he said, it wasn't "finished yet," to quickly insure the inappropriateness of any criticism I might have.

Funny how I could see him one day destroying his “novel" in a rage after a brief glimpse of insight that even if he could read would not have afforded him quite the same clarity.