Stay at Home

Andrea Chesman

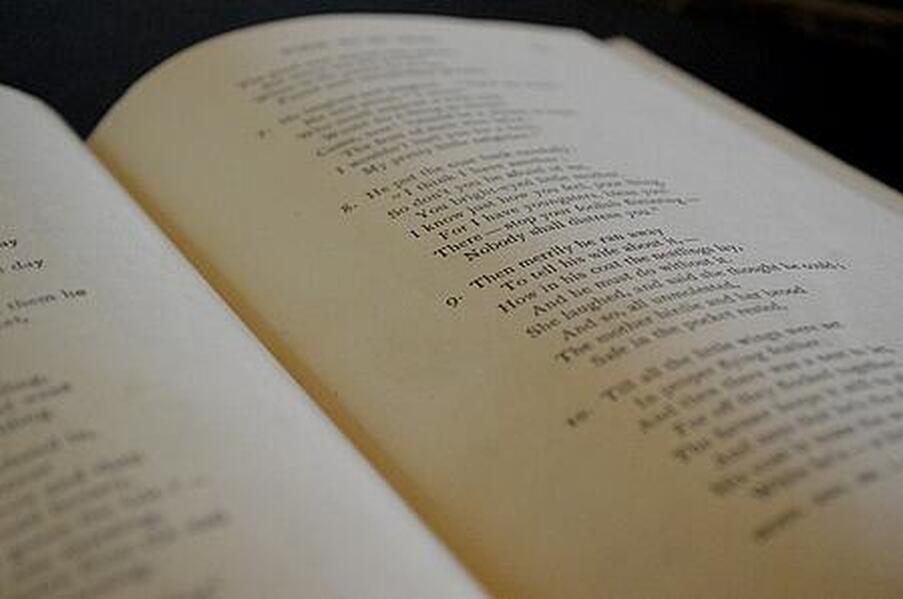

My mother provided my sister and me with the finer things in life by putting poetry anthologies in the bathroom. Other people had joke books or magazines or nothing at all, but we were expected to combine metabolism with metaphor. By the time I left for college, I had memorized much of the nineteenth and twentieth century canon--The Highway Man, No Man is an Island, The Road Not Taken, Ozymandias, Hope is the thing with feathers. I had a special fondness for Poe--The Raven, Annabel Lee, Eldorado.

It should surprise no one that I majored in English lit in college. I thought I was superior in intellect to my mother. She always had an aphorism handy--a stitch in time and the worms of the early bird. But I always had Blake and my candle burned on both ends. Now that my life is confined to the house to keep everyone safe from the pandemic, my brain seems to be atrophying, so I've returned the poetry anthologies to the bathroom. Horrible thought, am I turning into my mother? On cue, she bangs on the door.

"Madeline? Maddie are you in there?"

"I'm on the toilet, Mom."

"Well, when you will be out?"

"Soon, Mom, real soon."

"Lost time is never found again."

"What?"

"I'm going to be late for my appointment."

"No, you are not. You don't have an appointment today. I think Ellen is on the TV now. You like her. Go turn it on."

I vow I will not leave the bathroom until I have read one poem without interruption, start to finish. I re-open the anthology randomly and arrive at the one poem I do not want: Dylan Thomas's "Do not go gentle into that good night." Ironic, right? If Dylan Thomas's father had gone the way of my mother, he never would have written "old age should burn and rage against the dying of the light." Because that's exactly what my mother does. It isn't poetry: it's Alzheimer's, dementia, the raving of age.

I love my mother. I hate my mother. She can be lovely, she can be mean. She can disappear into silence for hours at a time, until I'm worried she's lost the ability to speak. Then she tells me I am a slob, I don't stand up straight, I need a decent haircut. She tells me I need to lose weight or I will never find a man who will have me, though she lives with me, my ever-patient husband Dan, our two children, and Summer, my daughter from before Dan.

My mother Marlene is still a beautiful woman, slender and upright, with remarkably soft skin. She is eighty-two years old and--point of pride--has "good" hair. Good hair in her book is luxuriously thick and willing to take a curl when prompted by Beverly who used to do her hair. Good hair is not mine, all curly and frizzy because I don't have the time to fuss with it.

If you think hair is unimportant or irrelevant, you haven't met my mother. Her week is organized by her Thursday visits to a hair salon, and she wakes up each morning--every single morning--asking if she will be visiting the hair salon that day. How can I tell her the pandemic has shut all the beauty parlors in town?

When I tell her she doesn't have an appointment, she snaps at me, accuses me of keeping her prisoner when she did nothing wrong. Last week she threw a bowl of oatmeal at me. Baby Zach in the high chair found it hilarious and dumped his oatmeal too, but my poor daughter Rosy fled in tears. Rosy is four and is frequently scared by my mother.

I know this means I could be psychologically scarring my daughter, and I should have put my mother in a home before the pandemic, or demanded that my sister take my mother in. But because I am the one staying at home while Denise has a job--a career--the care of our mother falls to me, to juggle who comes first: my mother or my kids. At one time Dan and I did consider putting her in a home, and we even visited a few; but all the well-lit "living rooms" and cheery activities directors couldn't distract us from the residents who demanded that we take them home, call them cabs, find their missing dogs. Now, even that option is gone as nursing homes have become death traps in the age of the Covid-19 virus. No, I'm not going to put my mother in a home, unless I absolutely have to. Dan says it will come to that. I say we will be signing her death certificate. Dan says everybody dies.

My attention has wandered, but my eyes have finished scanning the page; the poem is more than familiar. Rage, rage against the dying of the light. The afternoon is ebbing away. When my mother knocks on the door again, I open it and lead her downstairs to the kitchen and make her a cup of tea. The kids will be up from their naps soon, and I need to get supper started. Dan will be home at six. After supper, there will be baths, stories, dishes, and maybe, just maybe, if I'm lucky, and hour of adult conversation with Dan. I want to hear if the bank will give him the construction loan he is seeking, if his new hire actually showed up, if the world beyond my neighborhood has changed.

The kids wake from their naps. Rosy cuddles against my mother on the couch, furiously sucking her thumb back to life. They spend this time together often, though my mother is just as likely to push Rosy off the couch as she is to pick up a picture book and turn the pages, making up stories about the pictures. I don't know if she still can read. Zach wakes up ravenously hungry and cries until I shove enough yogurt in his mouth to bring his blood sugar back up.

~ ~ ~

The first time my mother ran away, we didn't even know she was gone. The police brought her back in the early morning, waking us by banging on the door. Thank goodness she had her purse with her, so they could figure out where she lived. This episode was followed by a series of runaways. No matter the barriers we put in her way, she was bound and determined to leave. But, there was one silver lining, she always went to the nearest bus stop. And the police, knowing who she is, would always pick her up and bring her home--night or day, dressed or in a flannel nightgown, barefoot or in heels.

The police have been friendly enough, at least to my mother, but they are growing impatient with Dan and me. It isn't good when "Officer Friendly" is so familiar we call him by his name--Bill Hannity--and he knows our whole family by first names. The last time Policeman Bill returned my mother, he started lecturing us. My mother put a hand on his chest and said, "He who fights and runs away will live to fight another day."

"See, that's what I mean. That's crazy talk. You need to get her into a secure facility, before I come upon her frozen on the sidewalk."

My sister blames Dan and me for being careless. And Dan, well, he is as understanding as he can be, under the circumstances...but let's just say, for the record, that two people who are always on alert listening for crying babies and wandering seniors don't have a great sex life.

~ ~ ~

Summer bounces downstairs, emerging from her room where she has been texting or Zooming or just zoning, and kisses Zach on his yogurt-smeared cheek. "Yum. Strawberry, my favorite, Messy Face."

Zach bounces with excitement, and I know yogurt time is over. So I wipe his face and hands and lift him out of his highchair. Summer, meanwhile, grabs a yogurt from the fridge, and sits down.

My mother and Rosy come into the kitchen--Rosy hoping for attention from Summer, my mother looking to criticize someone. "Are you sure I don't have an appointment this afternoon?"

"Quite sure."

She holds her hand out and studies her nails. "I need a manicure."

"And I need, I need--" Before I can speak words that can't be spoken, she turns to Summer. "Is that what you wore to school today? Don't you know a stitch in time saves nine?" Summer is dressed in layers of skinny shirts over skinny distressed jeans, her knees peeking through the artistically frayed and worn denim.

"Uh, oh. Gotta do my homework. Rosy, come on. You can help me. Zach, you too." Summer swoops down and sets Zach on her hip. "Mom, call me if you need my help?..." The rising inflection conveys her awareness of the help I always need.

"Playing with the kids is all the help I need. Thank you so much."

"I can't believe you let her go to school like that, her clothes all torn. People will think she doesn't know better."

Summer hasn't been to school in two weeks.

Summer is a blessing I don't deserve. When she was little, after I split from the boy I foolishly ran away with, she was in daycare much of the time. I don't know how she turned out so well. When Rosy was born, I swore I wouldn't miss out on her babyhood, like I missed out with Summer's. It's not like I loved working as a waitress. Now I am waitress and cook and cleaner.

You make your bed, you lie in it, is what my mother said back then, when Summer was a baby and I was a college drop-out. Not that English lit was going to prepare me for a fulfilling career. My future plans were always vague: travel, join the Peace Corps, teach English in China. I yearned for adventure; I would pick apples in the fall and be a ski bum all winter. I would harvest coffee in Nicaragua and dig wells in Africa, always collecting stories that would rummage in my brain, magically turning into novels and screenplays. I thought I would live in harmony with the seasons and with my friends and fellow travelers. But friends have a tendency to become lovers, and lovers have a tendency to split. Eventually it was just me struggling to make ends meet as a low-paid waitress in Keene, New Hampshire, with a baby and no child support.

Then I met Dan, a contractor who did some work for my sister, the lawyer. The next thing I knew Summer and I were living with Dan in fixer-uppers that I helped renovate and sell. It turns out I have a deft hand with a hammer and a paint brush.

Soon enough Rosy came along and my mother seemed to be drifting away, forgetting words, forgetting where she parked her car, then forgetting how to drive. I went from being a member of Dan's crew to full-time Mom and caretaker. Dan continued to flip houses and I stayed put. Now here we are: old mama, young mama, papa, and baby bears one, two, three living on a tree-lined street with sidewalks and maple trees. Like some kind of fairy tale with no happily ever after in sight.

~ ~ ~

Today started with breakfast, when my mother told me that Zach was too fat (he isn't too fat; he just hasn't started walking it off). When I made the beds, my mother followed me around, asking about her hair appointment, telling me stories about relatives I've never heard of before. In Rosy's room, she picked up a stuffed dog and said, "If you lay down with dogs, you wake up with fleas." Does she think the dog is real? I have no idea.

As I walked down the stairs with the dirty linens in my arms, my mother followed me. Her attention was caught by the framed photos that line the wall. At the top are my kids and Denise's, then our wedding pictures, Denise and husband with Mom and Dad, mine with just Mom. At the bottom, are pictures of her and Dad, their wedding pictures, their first house. She stops near the top and examines a photo. "Rosie's first birthday," I remind her.

"No it isn't. That's Denise. I remember quite clearly. I made a chocolate cake."

"Okay." No point in arguing. We continued down the stairs. She stopped again at her wedding picture. "I hated my dress. It hung on me like a sack. I couldn't eat, couldn't sleep. I wasn't sure I was doing the right thing..." She shook her head and followed me into the laundry room, the pictures forgotten.

I was rewarded with a few hours of respite as my mother dozed in front of the TV, but then she tried to leave. A few months ago, I would have distracted her with a trip to the supermarket, but that's no longer possible, not in these crazy times. Instead, I put Zach in the backpack, Rosy in the stroller and took my mother on a walk. "Where are we going?" she asked.

"We are going to look at houses for sale," I said. It doesn't matter what I say. As long as I can get her out the door, we only have to walk until she gets a little tired, then we turn back home.

~ ~ ~

Dusk is gathering. Dan pulls into the driveway, and I am grateful he is home because he is a necessary distraction for everyone. But, instead of coming straight into the house, Dan walks to the back of his Subaru and wrestles a bench out of his car and into the garage. It is stained grey, with a slatted seat and back--functional, anonymous, and simple. Odd since we have all the patio furniture we need.

"Did some shopping?" I ask as soon as he comes into the kitchen.

"I guess," he says, as Rosy wraps herself around one leg. "What's for supper?"

"What's in the garage?"

"We'll talk later."

~ ~ ~

Later is a beautiful plan. Later is the simple phrase "Bus Stop" painted on the back of the bench, which Dan sets on the edge of the lawn. It is, to say the least, an unusual lawn ornament. I don't care what the neighbors think.

The next day, I take my mother with me when I take Rosy and Zach to the playground and casually point out the new "bus stop." I'm not sure it registers, but that afternoon while I am settling the kids for their afternoon naps, my mother slips out and heads straight to the new bench. I see she is wearing a camel hair dress coat and a hat, so I let her sit for a few minutes in the weak afternoon sun. I join her with the baby monitor in my down jacket pocket.

"Hello," I say. "Have you been waiting long?"

She glances over at me and gives me a vague smile, tightening her grip on the purse in her lap. A thick layer of make-up--maybe multiple layers—gives her a clownish look. "Good things come to those who wait."

I'm not expecting anything good to come from this. "Personally, I don't mind waiting as long as it's not too cold." It is too cold for sitting there. My nose starts to ache where my glasses rest.

She continues to stare straight ahead. "You look very nice today," I say. "Going somewhere special?"

She turns and looks me over head to toe. "Just into town. I like to look nice. When you look good, you feel good." She sniffs. I'm pretty sure I don't smell bad even if I am wearing old clothes. "I have a daughter who looks something like you."

"Really?"

"Yes. Her name is Denise. She's prettier than you. She was always my favorite...I know, I'm not supposed to have a favorite. But I do. Yes, I do. She was my first born." She pulls the collar of her coat closer around her neck.

It isn't the first time I've heard Denise is her favorite. "Tell me about her."

"She's a lawyer. Imagine that. In my day, you didn't see too many women lawyers. But today, girls can do anything, be anything."

"Yes," I say. "The world has changed quite a bit since you were young. Did you want to be a lawyer?"

"Me?" she scoffs. "No I wanted to be an airline stewardess. See the world."

This is news to me. "What held you back? From being a stewardess?"

"You couldn't be a stewardess and be married. They would't let you. No, I missed my chance. I missed a lot of chances."

"But it seems like you had a good marriage. And two daughters who love you."

"Do I know you?"

"Yes," I answer. "You've known me for a long, long time."

The cold is seeping into my feet and my butt, and it has to be seeping into hers. "I know where we can get a cup of tea," I offer. "It would warm you up."

"Well," she says at last. "Tea would be lovely."

I put my hand under her elbow and help her up. She lets me take her arm as we walk back to the house. When we get into the kitchen, she looks around and says, "This place is a wreck. Don't you ever clean?"

I was just about to clean up after lunch when I went to fetch her. I tell her the maid quit, and she nods like she knew it all along.

~ ~ ~

Against all odds, the bus stop continues to work, night and day, snow or shine. One day she tells me that she had a boyfriend in high school she planned to marry but he was killed in a car accident right before high school graduation. "That's really sad," I say. I'm confused. I thought she married her high school sweetheart. I've seen his picture in her yearbook.

"He was the love of my life. I ended up marrying his best friend. It really wasn't the same. And we both knew it, but it seemed right at the time."

"You seemed pretty happy to me."

"I'm a great actress, just like Denise."

"Denise is a lawyer."

"Her husband plays around just like my husband did. Doesn't yours?"

"I don't think so."

"The wife is always the last to know." We sit in silence for a while. "I thought about leaving my husband, but I guess I lacked the courage. When I could have done something with my life."

"Like what?"

She doesn't answer, just stares straight ahead. I wonder if she is daydreaming of different ways her life might have gone, or if she is just lost in her brain fog. Eventually I stand and she comes back into the house with no coaxing.

~ ~ ~

The next day is sunny and bright, still chilly. Zach sleeps and Rosy lies awake in her bed, content for a change. I sit down next to my mother on the bench and from the baby monitor comes the sound of Rosie prattling to her dolls in the bedroom. My mother says, "Kids today are so undisciplined. They aren't taught proper manners. My grandson still eats with his hands."

"Really? How old is he?"

She shrugs. "Old enough to know better, I'm sure. Still, his mother does the best she can under the circumstances." This is the kindest thing my mother has said to me in months. She looks at me and says cryptically, "The barbarians are always at the gate."

Zach starts wailing, the sound loud and clear over the tiny speaker. I supposed he does sound like a barbarian. Or a cranky

baby--there's not much difference there. I tell my mother the bus had a flat tire and won't be coming today. She follows me into the house.

~ ~ ~

Snow keeps us in, and my mother hasn't wandered away for days. Snuggled under the blankets, Dan reaches for me tentatively. We kiss, we stroke, we are just becoming aroused, when we hear a scuffling from the front door. "What the heck?" says Dan.

"I think she's looking for boots."

"Well, it sounds like she's taking the front closet apart."

"Yeah. I hid her boots...Maybe she'll give up."

We listen and she does not give up. Or maybe she gives up on the boots but not on her decision to leave the house.

I struggle out of the warm bed and into yesterday's clothing shed as I made a mad dash into the warm covers.

My mother is standing by the bench because snow still covers the seat. I brush off the snow with mittened hands and gesture for her to sit.

"You'd think the city would clear off the snow."

"Yeah, but I guess they have their hands full with all the plowing."

She turns to me. "Do you work for the city?"

"No."

"Well, what do you do?"

"I stay home and take care of my mother and my kids."

"So you're an unpaid servant. Don't you want something more from your life? I have a daughter who ran away and became a freedom fighter. She was always fighting for more freedom."

Is that what I did? "What happened to her?"

"Who knows? I don't think she'd have ever settled for this." She gestures to the houses in front of her, all built in the same decade, all with the cars tucked into adjacent garages, evergreen bushes neatly wrapped in burlap. "She was going to do something with her life...something..."

"Something what?"

"Something grand. I was rooting for her to do some grand."

My life looks so much like hers did. Did she hate her life? Do I?

"Cat got your tongue?"

"No...But I think we missed the last bus. Shall we go in now?"

I lead my mother back into the house, help her out of her coat and sodden shoes, and tuck her into bed. She falls asleep instantly.

I think I may never be warm again. When I crawl into bed, Dan wraps himself around me and says, "Do you ever ask yourself whether this is worth it?"

"What? Is what worth it?"

"Keeping her here. Keeping her so well cared for when she doesn't even know who you are half the time."

"Dan! She's my mother!"

"She was your mother. That person is going. The one who's left? She's a stranger and she's never going to give you what you want."

"What is it that you think I want?"

"You want her to tell you that she's proud of you, that she appreciates what you do, that she loves you."

He is right, of course, and I have no answer. I feel him sink into the sleep of warm and safe, while I lay awake. I've been a good daughter and I care for her well, but she'll never be proud of me. And now, now I'm not even sure I'm proud of me.

Andrea Chesman

My mother provided my sister and me with the finer things in life by putting poetry anthologies in the bathroom. Other people had joke books or magazines or nothing at all, but we were expected to combine metabolism with metaphor. By the time I left for college, I had memorized much of the nineteenth and twentieth century canon--The Highway Man, No Man is an Island, The Road Not Taken, Ozymandias, Hope is the thing with feathers. I had a special fondness for Poe--The Raven, Annabel Lee, Eldorado.

It should surprise no one that I majored in English lit in college. I thought I was superior in intellect to my mother. She always had an aphorism handy--a stitch in time and the worms of the early bird. But I always had Blake and my candle burned on both ends. Now that my life is confined to the house to keep everyone safe from the pandemic, my brain seems to be atrophying, so I've returned the poetry anthologies to the bathroom. Horrible thought, am I turning into my mother? On cue, she bangs on the door.

"Madeline? Maddie are you in there?"

"I'm on the toilet, Mom."

"Well, when you will be out?"

"Soon, Mom, real soon."

"Lost time is never found again."

"What?"

"I'm going to be late for my appointment."

"No, you are not. You don't have an appointment today. I think Ellen is on the TV now. You like her. Go turn it on."

I vow I will not leave the bathroom until I have read one poem without interruption, start to finish. I re-open the anthology randomly and arrive at the one poem I do not want: Dylan Thomas's "Do not go gentle into that good night." Ironic, right? If Dylan Thomas's father had gone the way of my mother, he never would have written "old age should burn and rage against the dying of the light." Because that's exactly what my mother does. It isn't poetry: it's Alzheimer's, dementia, the raving of age.

I love my mother. I hate my mother. She can be lovely, she can be mean. She can disappear into silence for hours at a time, until I'm worried she's lost the ability to speak. Then she tells me I am a slob, I don't stand up straight, I need a decent haircut. She tells me I need to lose weight or I will never find a man who will have me, though she lives with me, my ever-patient husband Dan, our two children, and Summer, my daughter from before Dan.

My mother Marlene is still a beautiful woman, slender and upright, with remarkably soft skin. She is eighty-two years old and--point of pride--has "good" hair. Good hair in her book is luxuriously thick and willing to take a curl when prompted by Beverly who used to do her hair. Good hair is not mine, all curly and frizzy because I don't have the time to fuss with it.

If you think hair is unimportant or irrelevant, you haven't met my mother. Her week is organized by her Thursday visits to a hair salon, and she wakes up each morning--every single morning--asking if she will be visiting the hair salon that day. How can I tell her the pandemic has shut all the beauty parlors in town?

When I tell her she doesn't have an appointment, she snaps at me, accuses me of keeping her prisoner when she did nothing wrong. Last week she threw a bowl of oatmeal at me. Baby Zach in the high chair found it hilarious and dumped his oatmeal too, but my poor daughter Rosy fled in tears. Rosy is four and is frequently scared by my mother.

I know this means I could be psychologically scarring my daughter, and I should have put my mother in a home before the pandemic, or demanded that my sister take my mother in. But because I am the one staying at home while Denise has a job--a career--the care of our mother falls to me, to juggle who comes first: my mother or my kids. At one time Dan and I did consider putting her in a home, and we even visited a few; but all the well-lit "living rooms" and cheery activities directors couldn't distract us from the residents who demanded that we take them home, call them cabs, find their missing dogs. Now, even that option is gone as nursing homes have become death traps in the age of the Covid-19 virus. No, I'm not going to put my mother in a home, unless I absolutely have to. Dan says it will come to that. I say we will be signing her death certificate. Dan says everybody dies.

My attention has wandered, but my eyes have finished scanning the page; the poem is more than familiar. Rage, rage against the dying of the light. The afternoon is ebbing away. When my mother knocks on the door again, I open it and lead her downstairs to the kitchen and make her a cup of tea. The kids will be up from their naps soon, and I need to get supper started. Dan will be home at six. After supper, there will be baths, stories, dishes, and maybe, just maybe, if I'm lucky, and hour of adult conversation with Dan. I want to hear if the bank will give him the construction loan he is seeking, if his new hire actually showed up, if the world beyond my neighborhood has changed.

The kids wake from their naps. Rosy cuddles against my mother on the couch, furiously sucking her thumb back to life. They spend this time together often, though my mother is just as likely to push Rosy off the couch as she is to pick up a picture book and turn the pages, making up stories about the pictures. I don't know if she still can read. Zach wakes up ravenously hungry and cries until I shove enough yogurt in his mouth to bring his blood sugar back up.

~ ~ ~

The first time my mother ran away, we didn't even know she was gone. The police brought her back in the early morning, waking us by banging on the door. Thank goodness she had her purse with her, so they could figure out where she lived. This episode was followed by a series of runaways. No matter the barriers we put in her way, she was bound and determined to leave. But, there was one silver lining, she always went to the nearest bus stop. And the police, knowing who she is, would always pick her up and bring her home--night or day, dressed or in a flannel nightgown, barefoot or in heels.

The police have been friendly enough, at least to my mother, but they are growing impatient with Dan and me. It isn't good when "Officer Friendly" is so familiar we call him by his name--Bill Hannity--and he knows our whole family by first names. The last time Policeman Bill returned my mother, he started lecturing us. My mother put a hand on his chest and said, "He who fights and runs away will live to fight another day."

"See, that's what I mean. That's crazy talk. You need to get her into a secure facility, before I come upon her frozen on the sidewalk."

My sister blames Dan and me for being careless. And Dan, well, he is as understanding as he can be, under the circumstances...but let's just say, for the record, that two people who are always on alert listening for crying babies and wandering seniors don't have a great sex life.

~ ~ ~

Summer bounces downstairs, emerging from her room where she has been texting or Zooming or just zoning, and kisses Zach on his yogurt-smeared cheek. "Yum. Strawberry, my favorite, Messy Face."

Zach bounces with excitement, and I know yogurt time is over. So I wipe his face and hands and lift him out of his highchair. Summer, meanwhile, grabs a yogurt from the fridge, and sits down.

My mother and Rosy come into the kitchen--Rosy hoping for attention from Summer, my mother looking to criticize someone. "Are you sure I don't have an appointment this afternoon?"

"Quite sure."

She holds her hand out and studies her nails. "I need a manicure."

"And I need, I need--" Before I can speak words that can't be spoken, she turns to Summer. "Is that what you wore to school today? Don't you know a stitch in time saves nine?" Summer is dressed in layers of skinny shirts over skinny distressed jeans, her knees peeking through the artistically frayed and worn denim.

"Uh, oh. Gotta do my homework. Rosy, come on. You can help me. Zach, you too." Summer swoops down and sets Zach on her hip. "Mom, call me if you need my help?..." The rising inflection conveys her awareness of the help I always need.

"Playing with the kids is all the help I need. Thank you so much."

"I can't believe you let her go to school like that, her clothes all torn. People will think she doesn't know better."

Summer hasn't been to school in two weeks.

Summer is a blessing I don't deserve. When she was little, after I split from the boy I foolishly ran away with, she was in daycare much of the time. I don't know how she turned out so well. When Rosy was born, I swore I wouldn't miss out on her babyhood, like I missed out with Summer's. It's not like I loved working as a waitress. Now I am waitress and cook and cleaner.

You make your bed, you lie in it, is what my mother said back then, when Summer was a baby and I was a college drop-out. Not that English lit was going to prepare me for a fulfilling career. My future plans were always vague: travel, join the Peace Corps, teach English in China. I yearned for adventure; I would pick apples in the fall and be a ski bum all winter. I would harvest coffee in Nicaragua and dig wells in Africa, always collecting stories that would rummage in my brain, magically turning into novels and screenplays. I thought I would live in harmony with the seasons and with my friends and fellow travelers. But friends have a tendency to become lovers, and lovers have a tendency to split. Eventually it was just me struggling to make ends meet as a low-paid waitress in Keene, New Hampshire, with a baby and no child support.

Then I met Dan, a contractor who did some work for my sister, the lawyer. The next thing I knew Summer and I were living with Dan in fixer-uppers that I helped renovate and sell. It turns out I have a deft hand with a hammer and a paint brush.

Soon enough Rosy came along and my mother seemed to be drifting away, forgetting words, forgetting where she parked her car, then forgetting how to drive. I went from being a member of Dan's crew to full-time Mom and caretaker. Dan continued to flip houses and I stayed put. Now here we are: old mama, young mama, papa, and baby bears one, two, three living on a tree-lined street with sidewalks and maple trees. Like some kind of fairy tale with no happily ever after in sight.

~ ~ ~

Today started with breakfast, when my mother told me that Zach was too fat (he isn't too fat; he just hasn't started walking it off). When I made the beds, my mother followed me around, asking about her hair appointment, telling me stories about relatives I've never heard of before. In Rosy's room, she picked up a stuffed dog and said, "If you lay down with dogs, you wake up with fleas." Does she think the dog is real? I have no idea.

As I walked down the stairs with the dirty linens in my arms, my mother followed me. Her attention was caught by the framed photos that line the wall. At the top are my kids and Denise's, then our wedding pictures, Denise and husband with Mom and Dad, mine with just Mom. At the bottom, are pictures of her and Dad, their wedding pictures, their first house. She stops near the top and examines a photo. "Rosie's first birthday," I remind her.

"No it isn't. That's Denise. I remember quite clearly. I made a chocolate cake."

"Okay." No point in arguing. We continued down the stairs. She stopped again at her wedding picture. "I hated my dress. It hung on me like a sack. I couldn't eat, couldn't sleep. I wasn't sure I was doing the right thing..." She shook her head and followed me into the laundry room, the pictures forgotten.

I was rewarded with a few hours of respite as my mother dozed in front of the TV, but then she tried to leave. A few months ago, I would have distracted her with a trip to the supermarket, but that's no longer possible, not in these crazy times. Instead, I put Zach in the backpack, Rosy in the stroller and took my mother on a walk. "Where are we going?" she asked.

"We are going to look at houses for sale," I said. It doesn't matter what I say. As long as I can get her out the door, we only have to walk until she gets a little tired, then we turn back home.

~ ~ ~

Dusk is gathering. Dan pulls into the driveway, and I am grateful he is home because he is a necessary distraction for everyone. But, instead of coming straight into the house, Dan walks to the back of his Subaru and wrestles a bench out of his car and into the garage. It is stained grey, with a slatted seat and back--functional, anonymous, and simple. Odd since we have all the patio furniture we need.

"Did some shopping?" I ask as soon as he comes into the kitchen.

"I guess," he says, as Rosy wraps herself around one leg. "What's for supper?"

"What's in the garage?"

"We'll talk later."

~ ~ ~

Later is a beautiful plan. Later is the simple phrase "Bus Stop" painted on the back of the bench, which Dan sets on the edge of the lawn. It is, to say the least, an unusual lawn ornament. I don't care what the neighbors think.

The next day, I take my mother with me when I take Rosy and Zach to the playground and casually point out the new "bus stop." I'm not sure it registers, but that afternoon while I am settling the kids for their afternoon naps, my mother slips out and heads straight to the new bench. I see she is wearing a camel hair dress coat and a hat, so I let her sit for a few minutes in the weak afternoon sun. I join her with the baby monitor in my down jacket pocket.

"Hello," I say. "Have you been waiting long?"

She glances over at me and gives me a vague smile, tightening her grip on the purse in her lap. A thick layer of make-up--maybe multiple layers—gives her a clownish look. "Good things come to those who wait."

I'm not expecting anything good to come from this. "Personally, I don't mind waiting as long as it's not too cold." It is too cold for sitting there. My nose starts to ache where my glasses rest.

She continues to stare straight ahead. "You look very nice today," I say. "Going somewhere special?"

She turns and looks me over head to toe. "Just into town. I like to look nice. When you look good, you feel good." She sniffs. I'm pretty sure I don't smell bad even if I am wearing old clothes. "I have a daughter who looks something like you."

"Really?"

"Yes. Her name is Denise. She's prettier than you. She was always my favorite...I know, I'm not supposed to have a favorite. But I do. Yes, I do. She was my first born." She pulls the collar of her coat closer around her neck.

It isn't the first time I've heard Denise is her favorite. "Tell me about her."

"She's a lawyer. Imagine that. In my day, you didn't see too many women lawyers. But today, girls can do anything, be anything."

"Yes," I say. "The world has changed quite a bit since you were young. Did you want to be a lawyer?"

"Me?" she scoffs. "No I wanted to be an airline stewardess. See the world."

This is news to me. "What held you back? From being a stewardess?"

"You couldn't be a stewardess and be married. They would't let you. No, I missed my chance. I missed a lot of chances."

"But it seems like you had a good marriage. And two daughters who love you."

"Do I know you?"

"Yes," I answer. "You've known me for a long, long time."

The cold is seeping into my feet and my butt, and it has to be seeping into hers. "I know where we can get a cup of tea," I offer. "It would warm you up."

"Well," she says at last. "Tea would be lovely."

I put my hand under her elbow and help her up. She lets me take her arm as we walk back to the house. When we get into the kitchen, she looks around and says, "This place is a wreck. Don't you ever clean?"

I was just about to clean up after lunch when I went to fetch her. I tell her the maid quit, and she nods like she knew it all along.

~ ~ ~

Against all odds, the bus stop continues to work, night and day, snow or shine. One day she tells me that she had a boyfriend in high school she planned to marry but he was killed in a car accident right before high school graduation. "That's really sad," I say. I'm confused. I thought she married her high school sweetheart. I've seen his picture in her yearbook.

"He was the love of my life. I ended up marrying his best friend. It really wasn't the same. And we both knew it, but it seemed right at the time."

"You seemed pretty happy to me."

"I'm a great actress, just like Denise."

"Denise is a lawyer."

"Her husband plays around just like my husband did. Doesn't yours?"

"I don't think so."

"The wife is always the last to know." We sit in silence for a while. "I thought about leaving my husband, but I guess I lacked the courage. When I could have done something with my life."

"Like what?"

She doesn't answer, just stares straight ahead. I wonder if she is daydreaming of different ways her life might have gone, or if she is just lost in her brain fog. Eventually I stand and she comes back into the house with no coaxing.

~ ~ ~

The next day is sunny and bright, still chilly. Zach sleeps and Rosy lies awake in her bed, content for a change. I sit down next to my mother on the bench and from the baby monitor comes the sound of Rosie prattling to her dolls in the bedroom. My mother says, "Kids today are so undisciplined. They aren't taught proper manners. My grandson still eats with his hands."

"Really? How old is he?"

She shrugs. "Old enough to know better, I'm sure. Still, his mother does the best she can under the circumstances." This is the kindest thing my mother has said to me in months. She looks at me and says cryptically, "The barbarians are always at the gate."

Zach starts wailing, the sound loud and clear over the tiny speaker. I supposed he does sound like a barbarian. Or a cranky

baby--there's not much difference there. I tell my mother the bus had a flat tire and won't be coming today. She follows me into the house.

~ ~ ~

Snow keeps us in, and my mother hasn't wandered away for days. Snuggled under the blankets, Dan reaches for me tentatively. We kiss, we stroke, we are just becoming aroused, when we hear a scuffling from the front door. "What the heck?" says Dan.

"I think she's looking for boots."

"Well, it sounds like she's taking the front closet apart."

"Yeah. I hid her boots...Maybe she'll give up."

We listen and she does not give up. Or maybe she gives up on the boots but not on her decision to leave the house.

I struggle out of the warm bed and into yesterday's clothing shed as I made a mad dash into the warm covers.

My mother is standing by the bench because snow still covers the seat. I brush off the snow with mittened hands and gesture for her to sit.

"You'd think the city would clear off the snow."

"Yeah, but I guess they have their hands full with all the plowing."

She turns to me. "Do you work for the city?"

"No."

"Well, what do you do?"

"I stay home and take care of my mother and my kids."

"So you're an unpaid servant. Don't you want something more from your life? I have a daughter who ran away and became a freedom fighter. She was always fighting for more freedom."

Is that what I did? "What happened to her?"

"Who knows? I don't think she'd have ever settled for this." She gestures to the houses in front of her, all built in the same decade, all with the cars tucked into adjacent garages, evergreen bushes neatly wrapped in burlap. "She was going to do something with her life...something..."

"Something what?"

"Something grand. I was rooting for her to do some grand."

My life looks so much like hers did. Did she hate her life? Do I?

"Cat got your tongue?"

"No...But I think we missed the last bus. Shall we go in now?"

I lead my mother back into the house, help her out of her coat and sodden shoes, and tuck her into bed. She falls asleep instantly.

I think I may never be warm again. When I crawl into bed, Dan wraps himself around me and says, "Do you ever ask yourself whether this is worth it?"

"What? Is what worth it?"

"Keeping her here. Keeping her so well cared for when she doesn't even know who you are half the time."

"Dan! She's my mother!"

"She was your mother. That person is going. The one who's left? She's a stranger and she's never going to give you what you want."

"What is it that you think I want?"

"You want her to tell you that she's proud of you, that she appreciates what you do, that she loves you."

He is right, of course, and I have no answer. I feel him sink into the sleep of warm and safe, while I lay awake. I've been a good daughter and I care for her well, but she'll never be proud of me. And now, now I'm not even sure I'm proud of me.