Doop

Michael Royce

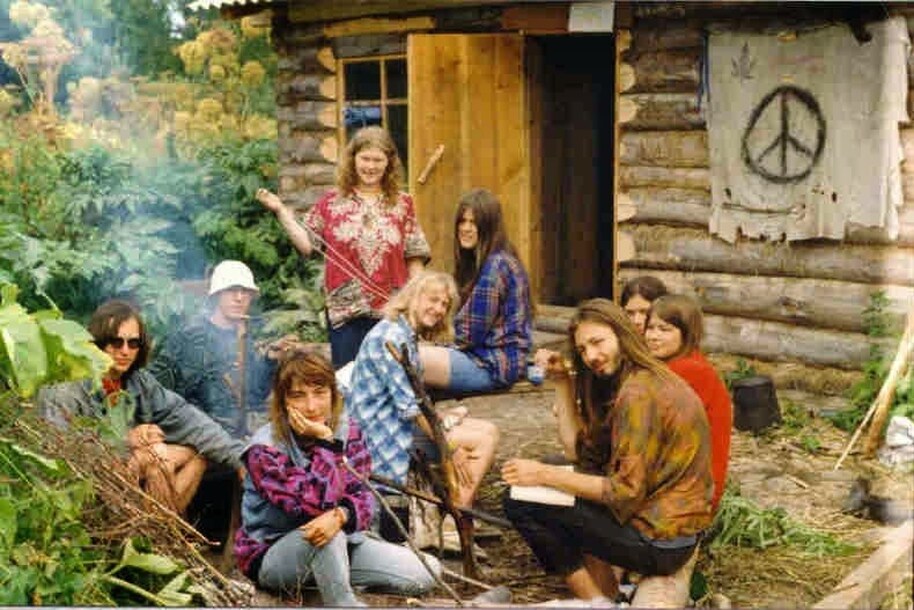

I sometimes dream of Peaceful Haven, our commune nestled in forty acres of tangled second growth at the foot of the Siskiyou Mountains, but I remain unable to fashion my past into a coherent story for others.

My first strong memory takes place one soft summer night in 1970 when I was six. I pretended to sleep in the darkness of our yurt under a faded Pendleton blanket covering a small futon. Outside, adults and the older kids lounged around the fire. A sweet odor spilled around the leather doorway, and through the yellowed plastic of the window above my bed, I saw the sky lit only partially by a crescent moon and hinting at a vastness in which glowing stars exist, alone and separate from each other.

My mother Gemma ducked inside the door. “You sleeping, Doop?” My name is Andrew Marshall, but my parents chose this nickname because that is what I called the dope they and their friends smoked in the evening.

“Yes, Momma,” I answered. She laughed, dropping the flap back into place, and I snuggled deeper into bed.

Later, with shadows of the dying fire flickering behind them, my parents stifled giggles and tumbled through the doorway. Mom flopped on a bed of pillows. Pops sat at a wood table liberated from a pile of donated furniture outside the local Goodwill while I pretended to sleep.

“Didn’t think Tanya had the backbone to stand up to Jock,” my mother said. “Telling him to get off his butt to help with the cooking and cleaning.”

“Nobody’s too good for honest labor.” Pops believed in equality and hard work. Bentley James Marshall, II—dad’s full name—was always “Pops” to me but “Bent” to the rest of our back-to-nature crowd. He was tall and stringy with “Mellow” tattooed on his right bicep. “In the fields, Jock ain’t always able to distinguish the cutting from the leaning end of a hoe.” His voice began to rise. “I’m up at 5 a.m. Till the garden. Feed the chickens.” Some of the other '60s drop-outs in the commune failed to meet his standards.

I peeked at him through half-shuttered eyes, studying his hands calloused from farming and mechanical repairs. His gaze turned inward as he varied his voice to mimic his father. “A waitress. Pregnant. This isn’t why we sent you to Princeton.” He coughed a not-so-happy laugh as he looked at Mom and remembered his dad’s summary after meeting her for the first and only time. After this parental harangue, he dropped out of college and stomped out of their lives, two months before his twenty-first birthday.

While Pops sank deeper into his imagined dialogue, Mom concentrated on her bedtime doobie, big as a small cigar. “Ohhh, you sound so uptight, like your father.”

Pops lumbered around the yurt, kicking up dust. On his third pass, he snagged the joint from Mom and took a hit. “Yeah…possibly.” The ends of his mouth quivered into the beginning of a smile. “Strive. Achieve. Accumulate.” He was on a roll now, enunciating in his father’s best bank executive voice.

The tent fell quiet at last, and I continued to feign sleep but watched Pops snuggle up to Mom. “You’re right, gypsy woman, you’re right; not easy to break free from your parents’ values.” The nuzzling grew embarrassing, and I rolled over as they pawed each other like teenagers.

Turned out Mom’s grandmother was, in fact, Roma. When Baba was angry, she’d throw things and shout curses punctuated by strange pronouncements like “People tumble before the blowing wind.” Mom spent all the time she could with her until she died. “I loved the way she swirled in her long dresses like a princess. The rest of the family was embarrassed.”

She broke from Pops’ embrace to pick up the reefer he had left balancing on the open mouth of a beer bottle. “You’re not the only one separated from their parents.” Her forehead wrinkled as she recited her family’s parting benediction when she and Bent headed out West: “Knocked up and hot to traipse after some crazed hippie.” Her face hardened. “That’s the life we’re escaping,” her dad had yelled. The family expected her to attend college, to meet and marry a professional, but her young gypsy heart had wanted freedom. She inhaled another deep draw. Her eyes softened, and she relaxed back into Pops' arms.

Turning to look at me, she whispered, “I’ll never leave you.” Her love covered me like a blanket, but I wondered about the grandparents I had never met. The small woodstove sputtered and throbbed, filling the muteness which hung over us.

But she did leave. Pops, too. Before we were ready. Them to depart and me to be left behind.

~ ~ ~

I remember Pops' sermons in the years before I became a teenager when the commune was young. “We’re building a home where wealth will never crush our souls.” When he preached, he still sounded of Princeton, but day-to-day he talked like the farmer he thought he had become.

“Yeah right, total utopia.” Mom didn’t buy his whole spiel. “Men make the decisions and women do the work. Pretty much like our parents.”

“Ain’t simple creating something different,” Pops sputtered back.

She didn’t disagree. Even at her most rancorous, she loved the place. “Ladies,” she announced to general snickers, “today we can tomatoes so tomorrow a new world flourishes from the tilled fields of the old.” She joined the laughter at her performance.

During canning season, sanitized mason jars towered in stacks on the tables. Hundreds of pounds of vegetables put up for the winter. Once, Mom posed in front of a pyramid of bottles flexing her bicep like Rosie the Riveter. “Woman Power,” she crowed. Her muscles weren’t puny either, tight little knots of sinew jutting from her upper arm. She was tough, not a flouncy woman like those gracing the covers of popular magazines sometimes showing up at the commune several months after their publication date.

The women never stopped working, or talking. “Hey, Marta, how long you going to be able to keep Rocket off you during this pregnancy.”

“Off me, you silly goose. Slacker better get Mr. Billy up more than two times a week or I’m going to knock on your door, borrow Lenny.”

The community homeschooled the younger children with different adults teaching, but after classes, the kids ran free, in and out of all the homes. We could cadge a meal with any family. Sometimes I was confused which “uncle” or “aunt” to seek out for comfort or for guidance, but there was never a question of having nobody to help.

At twelve, I joined the adults cultivating two acres of soy and corn while a third acre produced a flood of tomatoes, onions, chard, carrots, spinach, kale, and lettuce. With a hoe over my shoulder, I strode beside Pops on my first day. In the brightness of the morning, the certainty of where I fit within our community warmed me.

As we worked in the fields, somebody paused every fifth step to talk to someone in the next row until we all fell out for a breather. Pops didn’t allow me to smoke, but those who did bummed a cigarette from anyone with a pack.

“How many hippies does it take to screw in a light bulb?” Bill asked, dragging out a break. Work was never so important we could not pause for a joke.

Someone responded with a low snort. “Uh, don’t know.”

“Five. Four to marvel, and one to stick his finger in the socket.” This foolishness comforted us like our ritual greetings: hands clasped, fingers sliding down and locking to signify unity, and a parting shake of solidarity. We never passed each other without a wave, hug, or touch.

~ ~ ~

After eighth grade, I transferred to Ashland High School, fifteen miles from the farm. Like a butterfly, I wanted to escape from my cocoon into the alien world around me. Pops, Mom, and the others at the commune rejected the “rat race,” but other students boasted about their fathers’ important jobs and their mothers did not do hard outdoor physical labor like mine. I never talked about my home with its outhouse and water drawn from a communal pump. Living in two worlds, I came to consider myself not fully part of either.

By my junior year, farming started to fall apart and arguments about money began. Adults showed up for community labor less often. Some members of Peaceful Haven looked for jobs in Ashland.

After Pops landed work at a hotel, we moved into a wood-shingled rental in the southern part of the city. The clan back on the farm demanded a socialist division of the other’s wages. “We’re against capitalism and separation of humanity into haves and have-nots. Right?”

Pops and mom ignored this whining, as did the others developing a foothold in Ashland society, when they visited Peaceful Haven in the evening and on weekends to perform communal labor. Stoney, however, rose to the challenge: “You clowns want what we got? Get a job.” No amount of talking ever resolved this conflict.

During intermission in that year’s televised football face-off between the Ducks and Beavers, I turned to Pops, “How come we never see your parents?”

He shifted uncomfortably. “They wanted me to be different.”

“How do you mean?”

“My dad dreamed I’d be a banker like him.” Pops tripped a little as he searched for his words. “The idea sucked the air right out of me.”

“Yeah, but later couldn’t you patch things up?”

“My father forgot that his own dad worked in a steel mill. He was proud of being the first in his family to go to college, but I was more concerned about who I was than what I did.” Pops’ voice was serious, but I knew he loved this kind of existential questioning.

“Wouldn’t your dad have come to understand?”

“I doubt it. Anyway, I never forgave my parents for how they treated Mom, like trash I found on the street.”

“What if I don’t turn into what you expect?”

“Be true to yourself. That’s enough,” Pops said. But I was not sure yet who I was, much less what I might become.

In my last year of high school, I overheard my parents deep in conversation. “What’s it all about?” Pops asked. “I’m almost forty.” I was experiencing my own personal crisis at the time and perked up. “Everything’s changing. Hell, Stoney calls himself Stonewall and drinks gin and tonic instead of smoking dope.”

That spring, I visited a tattoo parlor on Siskiyou Boulevard in the seedy part of Ashland. I expected Pops to swagger when I showed him “Doop” burned into my left shoulder, but he only said, “Some things seem cool when you’re young, but they come with a cost.”

One day after Jock left to drive to work as a machinist at Southern Oregon University, he remembered something he had forgotten. He did a quick u-turn and discovered his wife and Stoney wrapped together like snakes. After kicking Stoney in the ass as he ran out the door, he chased his wife, covered only with a sheet, around the compound. Had this occurred earlier, we would have worked it out, maybe even found it funny, at least in the retelling, but no one was able to see the humor this time.

The remaining families moved into town or left the state in the next few months, and Stoney relocated to Los Angeles to sell Nautilus weight-lifting machines.

~ ~ ~

I enrolled in the local community college that fall, but this part of my life remains hazy because in the summer after my first year, my parents both died in a car crash.

Friends from Peaceful Haven flew back to attend the funeral from all over the country. Stonewall opened the memorial, representing the commune. He was bald on top but kept the rest of his hair well-trimmed. “Bent was a rock; Gemma, a whirlwind. They blew us forward and held us solid for almost fifteen years.”

I straightened in my seat in the front pew, trying to remember where the young Stoney with the ponytail chanting “Peace Now” had disappeared?

“Bent’s eyes brightened when he talked about Peaceful Haven.” While Stonewall reconstructed the past, I imagined Pops working in the field and fixing everything that broke, including our antique tractor. And Mom, leading the charge to bake in the early morning, teaching others how to squeeze production from garden plots and organizing our social life.

Nobody knew what to do with a 20-year old orphan, and I had no idea myself. Stoney referred me to an attorney. To my surprise, my parents had purchased life insurance as part of their reintegration into the middle class, leaving me a significant chunk of money.

At our first encounter, the lawyer said, “Half a million, that’s a lot for a young man.”

“Yeah, I guess.”

“What’re your plans?” he asked at our last meeting.

I didn’t have any but figured I needed to say something. “I’ll finish community college and transfer to a university.”

He shuffled papers and made as if he was considering standing up. I was not used to lawyers, but I was pretty sure this ended our discussion. He peeked at his watch without moving his wrist, and I rose and moved toward the door.

“Thanks for everything.” My parents had taught me to be polite.

“Good luck, Doop.”

I glanced back as I closed the door, and he was scanning another file on his desk.

~ ~ ~

Now, thirty years later, nobody calls me Doop. After I lost my parents, I struck out from shore and swam solo without pausing. Further I stroked. Pull, glide. I was magnificent.

While completing my MBA at Stanford, everyone called me Andy, then Andrew when I worked at Lehman’s. For the last ten years, I headed my own hedge fund where I am always addressed as Mr. Marshall. My Marshall Fund beats benchmarks year after year.

Yet, as I pushed forward through the undulating waters, land on the other side never drew closer. I remained alone and nothing but sea stretched to the horizon, without beginning or end.

I became too busy with what needed to be done to worry about why I chose one path instead of another. I forgot the past and never seemed to arrive at the future. My first marriage lasted only a year, and after that fell apart, I managed a couple of short flings before marrying again.

In our last serious talk, my second wife Marge probed about my childhood. “What was it like growing up as a hippie in Oregon?” I hated such cross examination, but then she was an attorney.

“It was okay, fine, no problems.” Everything that had happened to me before my parents’ death seemed unreal, a fairy tale about a boy living on a commune.

“A little detail, Andrew.” Her normal coloring darkened.

“We raised corn and stuff.” I never seemed able to resurrect Peaceful Haven to fit within the confines of my current life and talking about the past made me uneasy.

Her mouth pulled down. “There’s got to be more.”

“Well, my parents wanted to live the way they wanted, not how they were expected.”

“Did they succeed?”

“At the start we all shared what we had and the work.”

“Hmmnnn.” Marge concentrated as if searching for a hidden message in what I said.

“In the end, they failed. Everyone got shit jobs in a small town near where we lived.”

“To follow your dreams can be worthwhile…even if you never fulfill them.”

“I guess.”

“What were your mom and dad like?” Her voice trembled, but I was unsure why.

“They were young when a truck smashed into them.”

“I know, but what kind of people were they?” Her tone was sharp, and I sensed I was slipping into a zone of reality TV shows where the moderator asks you to reveal your deepest and most painful secrets.

She wanted more, but I had little to add. “Good people, trying to do the right thing.”

Marge’s cheeks fired up. Time stretched, and I remained silent. She walked in sharp bursts across the kitchen, toward and away from me.

“You could be a spy or terrorist for all I know.” She swept a saucer off the table to crash against the wall.

How crazy, I thought as shards of the cup hit the tile floor. I’m a big league money manager and wouldn’t have the slightest idea how to plot a car bombing. “Everyone else thinks I’m a success,” I said. I couldn’t understand her anger or what she wanted from me. After this divorce, I dated a rotating cast of women but lived alone.

Recently, at a conference where I was a speaker, Sandy introduced herself. We exchanged business cards and arranged to meet a week later for lunch.

~ ~ ~

Sandy flashes an engaging smile as she sails toward me across the restaurant floor. She is slender and holds herself with dignity. Although I am fifteen years older, I am accustomed to dating younger and attractive women.

After the usual exchanges, I steer us into a long discussion about upcoming Federal Reserve announcements. I am the author of The Inflationary Impact of Interest Rate Hikes and am frequently quoted in financial journals. Sandy tracks what I am saying, and her questions are probing.

Toward the end of the main course, she diverts the conversation. “All this complicated high finance is a little overwhelming.” There are light notes in her laugh, almost a gurgle of self-amusement at life’s curious transitions. “I was an art major as an undergraduate, but after ten years, I realized nobody pays real money for art so I returned to business school. Goldman Sachs hired me two years ago with my newly-minted MBA.”

“As an analyst,” she says during dessert, “I earn enough to support my true passions.” The bill comes, and I do not have time to explore what these might be. I note, however, that her black hair brushes the right side of her forehead, the clearness of her skin, and the almost almond shape of her green-brown eyes. The curves in the emerald of her silk blouse, opened decorously to a second button, hint of a sensuous body. She is even more beautiful than the actresses and models I normally date, and I invite her to a play that Saturday.

In preparation to pick Sandy up for the opening of The Piano Lesson at the Signature Theater, I stroke downward with a razor, careful to avoid the wrinkles developing around the edges of my mouth. After shaving, I step into the shower where, under the pulsing stream, an image of Sandy’s face and body arouses me. In front of the still misty mirror afterwards, I loop my tie into a thick Windsor knot. Fearing unscripted moments in the evening that might poke into the past instead of remaining in the safety of the present, I pause to sit in an overstuffed chair in my bedroom to construct conversational gambits.

“I’m so looking forward to this,” Sandy says as she steps into the cab.

During the intermission, I attempt one of the subjects I had play-acted before leaving home. “Black theater’s a self-defeating term.”

“Why?” she answers. I am unsure if she does not understand what I mean or is trying to initiate real conversation.

“To call it a theater of the African-American experience diminishes its importance.” I had digested several online critiques to ensure a stock of insightful commentary, the same careful preparation I exercise in courting new investors.

“But it’s rooted in the lives of black people, Andrew.”

With a mental lurch, I realize she is nosing around for what I really think. I calm my voice to maintain distance. “Okay, but the theme shouldn’t be parochial to one race.” Here I again paraphrase a review I had studied earlier.

“August Wilson’s message that family history haunts the present is universal. He simply explores this idea in African-American Pittsburgh of the 1930s.” Her voice is animated, but I become tentative, and conversation winds down. I continue to sit beside her for the second act but imagine myself to be alone.

After last curtain, we talk casually and walk outside to flag a cab. Opening the door for her, I reach in and hand a fifty to the driver. “Take her wherever she wants to go.”

“Why are you blowing me off like this?” Sandy’s voice is low, and her eyes no longer sparkle.

“It’s not you, it’s me.”

I wave the taxi off and stand apart from the crowd, chattering and touching in front of the theater before they make their way home.

Michael Royce

I sometimes dream of Peaceful Haven, our commune nestled in forty acres of tangled second growth at the foot of the Siskiyou Mountains, but I remain unable to fashion my past into a coherent story for others.

My first strong memory takes place one soft summer night in 1970 when I was six. I pretended to sleep in the darkness of our yurt under a faded Pendleton blanket covering a small futon. Outside, adults and the older kids lounged around the fire. A sweet odor spilled around the leather doorway, and through the yellowed plastic of the window above my bed, I saw the sky lit only partially by a crescent moon and hinting at a vastness in which glowing stars exist, alone and separate from each other.

My mother Gemma ducked inside the door. “You sleeping, Doop?” My name is Andrew Marshall, but my parents chose this nickname because that is what I called the dope they and their friends smoked in the evening.

“Yes, Momma,” I answered. She laughed, dropping the flap back into place, and I snuggled deeper into bed.

Later, with shadows of the dying fire flickering behind them, my parents stifled giggles and tumbled through the doorway. Mom flopped on a bed of pillows. Pops sat at a wood table liberated from a pile of donated furniture outside the local Goodwill while I pretended to sleep.

“Didn’t think Tanya had the backbone to stand up to Jock,” my mother said. “Telling him to get off his butt to help with the cooking and cleaning.”

“Nobody’s too good for honest labor.” Pops believed in equality and hard work. Bentley James Marshall, II—dad’s full name—was always “Pops” to me but “Bent” to the rest of our back-to-nature crowd. He was tall and stringy with “Mellow” tattooed on his right bicep. “In the fields, Jock ain’t always able to distinguish the cutting from the leaning end of a hoe.” His voice began to rise. “I’m up at 5 a.m. Till the garden. Feed the chickens.” Some of the other '60s drop-outs in the commune failed to meet his standards.

I peeked at him through half-shuttered eyes, studying his hands calloused from farming and mechanical repairs. His gaze turned inward as he varied his voice to mimic his father. “A waitress. Pregnant. This isn’t why we sent you to Princeton.” He coughed a not-so-happy laugh as he looked at Mom and remembered his dad’s summary after meeting her for the first and only time. After this parental harangue, he dropped out of college and stomped out of their lives, two months before his twenty-first birthday.

While Pops sank deeper into his imagined dialogue, Mom concentrated on her bedtime doobie, big as a small cigar. “Ohhh, you sound so uptight, like your father.”

Pops lumbered around the yurt, kicking up dust. On his third pass, he snagged the joint from Mom and took a hit. “Yeah…possibly.” The ends of his mouth quivered into the beginning of a smile. “Strive. Achieve. Accumulate.” He was on a roll now, enunciating in his father’s best bank executive voice.

The tent fell quiet at last, and I continued to feign sleep but watched Pops snuggle up to Mom. “You’re right, gypsy woman, you’re right; not easy to break free from your parents’ values.” The nuzzling grew embarrassing, and I rolled over as they pawed each other like teenagers.

Turned out Mom’s grandmother was, in fact, Roma. When Baba was angry, she’d throw things and shout curses punctuated by strange pronouncements like “People tumble before the blowing wind.” Mom spent all the time she could with her until she died. “I loved the way she swirled in her long dresses like a princess. The rest of the family was embarrassed.”

She broke from Pops’ embrace to pick up the reefer he had left balancing on the open mouth of a beer bottle. “You’re not the only one separated from their parents.” Her forehead wrinkled as she recited her family’s parting benediction when she and Bent headed out West: “Knocked up and hot to traipse after some crazed hippie.” Her face hardened. “That’s the life we’re escaping,” her dad had yelled. The family expected her to attend college, to meet and marry a professional, but her young gypsy heart had wanted freedom. She inhaled another deep draw. Her eyes softened, and she relaxed back into Pops' arms.

Turning to look at me, she whispered, “I’ll never leave you.” Her love covered me like a blanket, but I wondered about the grandparents I had never met. The small woodstove sputtered and throbbed, filling the muteness which hung over us.

But she did leave. Pops, too. Before we were ready. Them to depart and me to be left behind.

~ ~ ~

I remember Pops' sermons in the years before I became a teenager when the commune was young. “We’re building a home where wealth will never crush our souls.” When he preached, he still sounded of Princeton, but day-to-day he talked like the farmer he thought he had become.

“Yeah right, total utopia.” Mom didn’t buy his whole spiel. “Men make the decisions and women do the work. Pretty much like our parents.”

“Ain’t simple creating something different,” Pops sputtered back.

She didn’t disagree. Even at her most rancorous, she loved the place. “Ladies,” she announced to general snickers, “today we can tomatoes so tomorrow a new world flourishes from the tilled fields of the old.” She joined the laughter at her performance.

During canning season, sanitized mason jars towered in stacks on the tables. Hundreds of pounds of vegetables put up for the winter. Once, Mom posed in front of a pyramid of bottles flexing her bicep like Rosie the Riveter. “Woman Power,” she crowed. Her muscles weren’t puny either, tight little knots of sinew jutting from her upper arm. She was tough, not a flouncy woman like those gracing the covers of popular magazines sometimes showing up at the commune several months after their publication date.

The women never stopped working, or talking. “Hey, Marta, how long you going to be able to keep Rocket off you during this pregnancy.”

“Off me, you silly goose. Slacker better get Mr. Billy up more than two times a week or I’m going to knock on your door, borrow Lenny.”

The community homeschooled the younger children with different adults teaching, but after classes, the kids ran free, in and out of all the homes. We could cadge a meal with any family. Sometimes I was confused which “uncle” or “aunt” to seek out for comfort or for guidance, but there was never a question of having nobody to help.

At twelve, I joined the adults cultivating two acres of soy and corn while a third acre produced a flood of tomatoes, onions, chard, carrots, spinach, kale, and lettuce. With a hoe over my shoulder, I strode beside Pops on my first day. In the brightness of the morning, the certainty of where I fit within our community warmed me.

As we worked in the fields, somebody paused every fifth step to talk to someone in the next row until we all fell out for a breather. Pops didn’t allow me to smoke, but those who did bummed a cigarette from anyone with a pack.

“How many hippies does it take to screw in a light bulb?” Bill asked, dragging out a break. Work was never so important we could not pause for a joke.

Someone responded with a low snort. “Uh, don’t know.”

“Five. Four to marvel, and one to stick his finger in the socket.” This foolishness comforted us like our ritual greetings: hands clasped, fingers sliding down and locking to signify unity, and a parting shake of solidarity. We never passed each other without a wave, hug, or touch.

~ ~ ~

After eighth grade, I transferred to Ashland High School, fifteen miles from the farm. Like a butterfly, I wanted to escape from my cocoon into the alien world around me. Pops, Mom, and the others at the commune rejected the “rat race,” but other students boasted about their fathers’ important jobs and their mothers did not do hard outdoor physical labor like mine. I never talked about my home with its outhouse and water drawn from a communal pump. Living in two worlds, I came to consider myself not fully part of either.

By my junior year, farming started to fall apart and arguments about money began. Adults showed up for community labor less often. Some members of Peaceful Haven looked for jobs in Ashland.

After Pops landed work at a hotel, we moved into a wood-shingled rental in the southern part of the city. The clan back on the farm demanded a socialist division of the other’s wages. “We’re against capitalism and separation of humanity into haves and have-nots. Right?”

Pops and mom ignored this whining, as did the others developing a foothold in Ashland society, when they visited Peaceful Haven in the evening and on weekends to perform communal labor. Stoney, however, rose to the challenge: “You clowns want what we got? Get a job.” No amount of talking ever resolved this conflict.

During intermission in that year’s televised football face-off between the Ducks and Beavers, I turned to Pops, “How come we never see your parents?”

He shifted uncomfortably. “They wanted me to be different.”

“How do you mean?”

“My dad dreamed I’d be a banker like him.” Pops tripped a little as he searched for his words. “The idea sucked the air right out of me.”

“Yeah, but later couldn’t you patch things up?”

“My father forgot that his own dad worked in a steel mill. He was proud of being the first in his family to go to college, but I was more concerned about who I was than what I did.” Pops’ voice was serious, but I knew he loved this kind of existential questioning.

“Wouldn’t your dad have come to understand?”

“I doubt it. Anyway, I never forgave my parents for how they treated Mom, like trash I found on the street.”

“What if I don’t turn into what you expect?”

“Be true to yourself. That’s enough,” Pops said. But I was not sure yet who I was, much less what I might become.

In my last year of high school, I overheard my parents deep in conversation. “What’s it all about?” Pops asked. “I’m almost forty.” I was experiencing my own personal crisis at the time and perked up. “Everything’s changing. Hell, Stoney calls himself Stonewall and drinks gin and tonic instead of smoking dope.”

That spring, I visited a tattoo parlor on Siskiyou Boulevard in the seedy part of Ashland. I expected Pops to swagger when I showed him “Doop” burned into my left shoulder, but he only said, “Some things seem cool when you’re young, but they come with a cost.”

One day after Jock left to drive to work as a machinist at Southern Oregon University, he remembered something he had forgotten. He did a quick u-turn and discovered his wife and Stoney wrapped together like snakes. After kicking Stoney in the ass as he ran out the door, he chased his wife, covered only with a sheet, around the compound. Had this occurred earlier, we would have worked it out, maybe even found it funny, at least in the retelling, but no one was able to see the humor this time.

The remaining families moved into town or left the state in the next few months, and Stoney relocated to Los Angeles to sell Nautilus weight-lifting machines.

~ ~ ~

I enrolled in the local community college that fall, but this part of my life remains hazy because in the summer after my first year, my parents both died in a car crash.

Friends from Peaceful Haven flew back to attend the funeral from all over the country. Stonewall opened the memorial, representing the commune. He was bald on top but kept the rest of his hair well-trimmed. “Bent was a rock; Gemma, a whirlwind. They blew us forward and held us solid for almost fifteen years.”

I straightened in my seat in the front pew, trying to remember where the young Stoney with the ponytail chanting “Peace Now” had disappeared?

“Bent’s eyes brightened when he talked about Peaceful Haven.” While Stonewall reconstructed the past, I imagined Pops working in the field and fixing everything that broke, including our antique tractor. And Mom, leading the charge to bake in the early morning, teaching others how to squeeze production from garden plots and organizing our social life.

Nobody knew what to do with a 20-year old orphan, and I had no idea myself. Stoney referred me to an attorney. To my surprise, my parents had purchased life insurance as part of their reintegration into the middle class, leaving me a significant chunk of money.

At our first encounter, the lawyer said, “Half a million, that’s a lot for a young man.”

“Yeah, I guess.”

“What’re your plans?” he asked at our last meeting.

I didn’t have any but figured I needed to say something. “I’ll finish community college and transfer to a university.”

He shuffled papers and made as if he was considering standing up. I was not used to lawyers, but I was pretty sure this ended our discussion. He peeked at his watch without moving his wrist, and I rose and moved toward the door.

“Thanks for everything.” My parents had taught me to be polite.

“Good luck, Doop.”

I glanced back as I closed the door, and he was scanning another file on his desk.

~ ~ ~

Now, thirty years later, nobody calls me Doop. After I lost my parents, I struck out from shore and swam solo without pausing. Further I stroked. Pull, glide. I was magnificent.

While completing my MBA at Stanford, everyone called me Andy, then Andrew when I worked at Lehman’s. For the last ten years, I headed my own hedge fund where I am always addressed as Mr. Marshall. My Marshall Fund beats benchmarks year after year.

Yet, as I pushed forward through the undulating waters, land on the other side never drew closer. I remained alone and nothing but sea stretched to the horizon, without beginning or end.

I became too busy with what needed to be done to worry about why I chose one path instead of another. I forgot the past and never seemed to arrive at the future. My first marriage lasted only a year, and after that fell apart, I managed a couple of short flings before marrying again.

In our last serious talk, my second wife Marge probed about my childhood. “What was it like growing up as a hippie in Oregon?” I hated such cross examination, but then she was an attorney.

“It was okay, fine, no problems.” Everything that had happened to me before my parents’ death seemed unreal, a fairy tale about a boy living on a commune.

“A little detail, Andrew.” Her normal coloring darkened.

“We raised corn and stuff.” I never seemed able to resurrect Peaceful Haven to fit within the confines of my current life and talking about the past made me uneasy.

Her mouth pulled down. “There’s got to be more.”

“Well, my parents wanted to live the way they wanted, not how they were expected.”

“Did they succeed?”

“At the start we all shared what we had and the work.”

“Hmmnnn.” Marge concentrated as if searching for a hidden message in what I said.

“In the end, they failed. Everyone got shit jobs in a small town near where we lived.”

“To follow your dreams can be worthwhile…even if you never fulfill them.”

“I guess.”

“What were your mom and dad like?” Her voice trembled, but I was unsure why.

“They were young when a truck smashed into them.”

“I know, but what kind of people were they?” Her tone was sharp, and I sensed I was slipping into a zone of reality TV shows where the moderator asks you to reveal your deepest and most painful secrets.

She wanted more, but I had little to add. “Good people, trying to do the right thing.”

Marge’s cheeks fired up. Time stretched, and I remained silent. She walked in sharp bursts across the kitchen, toward and away from me.

“You could be a spy or terrorist for all I know.” She swept a saucer off the table to crash against the wall.

How crazy, I thought as shards of the cup hit the tile floor. I’m a big league money manager and wouldn’t have the slightest idea how to plot a car bombing. “Everyone else thinks I’m a success,” I said. I couldn’t understand her anger or what she wanted from me. After this divorce, I dated a rotating cast of women but lived alone.

Recently, at a conference where I was a speaker, Sandy introduced herself. We exchanged business cards and arranged to meet a week later for lunch.

~ ~ ~

Sandy flashes an engaging smile as she sails toward me across the restaurant floor. She is slender and holds herself with dignity. Although I am fifteen years older, I am accustomed to dating younger and attractive women.

After the usual exchanges, I steer us into a long discussion about upcoming Federal Reserve announcements. I am the author of The Inflationary Impact of Interest Rate Hikes and am frequently quoted in financial journals. Sandy tracks what I am saying, and her questions are probing.

Toward the end of the main course, she diverts the conversation. “All this complicated high finance is a little overwhelming.” There are light notes in her laugh, almost a gurgle of self-amusement at life’s curious transitions. “I was an art major as an undergraduate, but after ten years, I realized nobody pays real money for art so I returned to business school. Goldman Sachs hired me two years ago with my newly-minted MBA.”

“As an analyst,” she says during dessert, “I earn enough to support my true passions.” The bill comes, and I do not have time to explore what these might be. I note, however, that her black hair brushes the right side of her forehead, the clearness of her skin, and the almost almond shape of her green-brown eyes. The curves in the emerald of her silk blouse, opened decorously to a second button, hint of a sensuous body. She is even more beautiful than the actresses and models I normally date, and I invite her to a play that Saturday.

In preparation to pick Sandy up for the opening of The Piano Lesson at the Signature Theater, I stroke downward with a razor, careful to avoid the wrinkles developing around the edges of my mouth. After shaving, I step into the shower where, under the pulsing stream, an image of Sandy’s face and body arouses me. In front of the still misty mirror afterwards, I loop my tie into a thick Windsor knot. Fearing unscripted moments in the evening that might poke into the past instead of remaining in the safety of the present, I pause to sit in an overstuffed chair in my bedroom to construct conversational gambits.

“I’m so looking forward to this,” Sandy says as she steps into the cab.

During the intermission, I attempt one of the subjects I had play-acted before leaving home. “Black theater’s a self-defeating term.”

“Why?” she answers. I am unsure if she does not understand what I mean or is trying to initiate real conversation.

“To call it a theater of the African-American experience diminishes its importance.” I had digested several online critiques to ensure a stock of insightful commentary, the same careful preparation I exercise in courting new investors.

“But it’s rooted in the lives of black people, Andrew.”

With a mental lurch, I realize she is nosing around for what I really think. I calm my voice to maintain distance. “Okay, but the theme shouldn’t be parochial to one race.” Here I again paraphrase a review I had studied earlier.

“August Wilson’s message that family history haunts the present is universal. He simply explores this idea in African-American Pittsburgh of the 1930s.” Her voice is animated, but I become tentative, and conversation winds down. I continue to sit beside her for the second act but imagine myself to be alone.

After last curtain, we talk casually and walk outside to flag a cab. Opening the door for her, I reach in and hand a fifty to the driver. “Take her wherever she wants to go.”

“Why are you blowing me off like this?” Sandy’s voice is low, and her eyes no longer sparkle.

“It’s not you, it’s me.”

I wave the taxi off and stand apart from the crowd, chattering and touching in front of the theater before they make their way home.