Three Guest-Friends

Tom Joyce

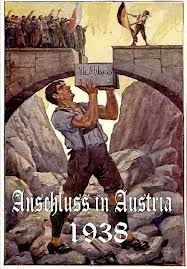

It was early on an April day in 1938, one week after approval of the Anschluss, the incorporation of Austria into the Greater Reich, and Vienna Police Inspector Karl Marbach was wondering how bad things were going to get now that the Nazis had total power. Alone in his lover’s flat, Karl placed a platter on the gramophone, and it was just starting to play when he heard familiar sounds in the hallway. He went to the door and pulled it open.

Directly in front of Karl was his lover. Constanze Tandler was Italian. An established actress in Italy, she often performed in France, and was currently performing as the lead in a play at Vienna’s Volkstheater. Constanze was fluent in several languages. Eighteen year-old Marianne Frish, a stranger to the flat, was holding Constanze’s hand. Standing behind them was Anna Krassny, who was born and raised in Vienna. Like Constanze, Anna was an actress. Anna usually performed at the Burgtheater. In recent weeks Constanze and Anna had become close friends.

Marianne’s large brown eyes brightened as she listened to the music playing on a gramophone. Her head began weaving in delighted response to what she recognized as a carefree tune in Beethoven’s Pastoral. Karl grasped the teenager’s hand, pressed it to his mouth, and drew her forward. She smiled shyly. Karl smiled back in a reassuring manner, then shifted his attention to Constanze and Anna. While he watched, Anna stared at him, took one step backward as though to gain momentum, and rushed forward.

No hand kiss would suffice for Anna. She demanded a hug and got it. Then she demanded a kiss on the mouth and got it. A few years ago, Karl had loved Anna in the romantic way. Now there were no romantic feelings, but they shared a friendship that was powerful.

Anna drew her head back to peer over her shoulder at Constanze. They exchanged grins of understanding.

While Anna returned her attention to Karl, Constanze remained standing in the doorway with a broad-brimmed hat pushed back on her head.

Anna laughed a throaty laugh, pulled Karl close, and said over her shoulder, “Constanze, if you had not become such a good friend in recent days, I would take this man away from you.”

Constanze acknowledged the joke by sticking out her tongue at Anna. Then she turned toward Marianne and said, “Sweet one, dear sweet one, please find some drinks to freshen us. There is some marvelous Schilcher Rose for those of us who have the taste to appreciate good wine. I assume that includes you. As for this oafish man, give him a glass of his schnapps—his kümmel.”

Anna joined Marianne at a cabinet at the far side of the room to prepare the drinks. They found four glasses and set them on the top of the cabinet: three long-stemmed, crystal-clear wine glasses for the women, and a plain, flat-bottomed glass for the man. While the drinks were being prepared, Karl stared at Constanze, who was still standing in the doorway. Her head and her shoulders were moving in time to the gaiety in Beethoven’s music spilling forth from the gramophone.

Karl walked across the room, took Constanze by the arm and led her over to the sofa. They were still settling themselves on the sofa when Marianne walked up to them holding a tray upon which were drinks. Karl reached out and secured for Constanze a long-stemmed wine glass filled with Schilcher Rose, handed it to her, and then took from the tray the plain, flat-bottomed glass containing his kümmel.

Anna walked over, retrieved from the tray a glass filled with Schilcher Rose, and made herself comfortable in a heavily stuffed chair facing the sofa. After setting aside the tray, Marianne took a glass of Schilcher Rose for herself and sat at the far end of the sofa.

Drawing Karl’s arm close around her, Constanze lifted her glass and proclaimed an ancient Greek toast, a very special celebration of hospitality she reserved only for people to whom she felt a close bond: “Guest-Friends!”

Anna held up her glass and echoed the toast: “Guest-Friends!”

Marianne looked puzzled, but lifted her glass and spoke the toast: “Guest-Friends!”

With one arm around Constanze, Karl used his free hand to raise his glass. He spoke the toast with solemn deliberation: “Guest-Friends!”

The ancient Greek toast was completed, and Anna decided to return the conversation to playful mischief. “Well, Marianne, because you and I haven’t seen much of each other before, and because we are now guest-friends, I will share with you a secret. The secret I share with you is that Karl is successful with women because he is willing to be a little afraid of them.”

“I make no secret of it,” Karl said. “Without some fear, there is no awe, and without awe it is impossible for a man to fully appreciate a woman.”

Constanze and Anna shared a glance, and began laughing. Anna’s deep, throaty laughter joined with Constanze’s musical E-flat laughter and a melody of laughter was created. Marianne’s playful giggling leavened the melody.

Karl shook his head, and drew his arm more tightly around Constanze. He nodded contentedly when she maneuvered around until she was able to rest her head on his chest. Her E-flat laughter continued.

Marianne stopped giggling long enough to say to Constanze, “I haven’t told you yet -- we have only been friends for a few days -- but I got a letter today from my boy friend Emile who is off visiting some business friends in France. I have told you that Emile and I met at the Musikverein. That was six months ago. You have never told me. I wonder . . . where did you and the police inspector . . . ?”

Constanze placed her hand on her lover’s stomach. “We are Guest-Friends. Don’t call him police inspector. You may call him Karl or Guest-Friend, but nothing else. Not tonight. Not in this place. Guest-friendship is about equality. Now, to answer the question you were starting to ask, Karl and I met in the Café Central last year.”

Karl looked down at Constanze’s hand. He hoped she was going to keep it on his stomach. He said to Marianne, “The first time I saw Constanze was not one year ago. It was ten years earlier. She was on the stage right here in Vienna playing the part of Margarethe in Faust. I must say I never saw any other actress play the part of that handmaid of goodness with such expressive femininity.”

Constanze lifted her head. She kept her hand on Karl’s stomach as she said to Marianne, “In that play Margarethe is virtuous, but not timid. It is a common mistake to portray Margarethe as the timid handmaid of goodness.”

“The night I saw it,” Karl said, “you made her sensuality very obvious.” He knew that. Constanze was proud of having played the part that way.

“Oh, what a great play.” Marianne exclaimed to Constanze. “I wish I had seen you in it. It is one of my favorite plays.”

Karl looked at Constanze and spoke one of the immortal lines from Faust. “The eternal feminine image that leads men on.” He made a pretended gasp when Constanze shoved her elbow with playful force against his ribs.

Anna laughed cheerily. . .

Constanze said, “Soon the play I am doing will close. I am going to have trouble doing another play in Vienna even if I agree to take a small part. I have refused to sign that terrible piece of paper saying I am not a Jew.”

With wide open eyes, Marianne asked Constanze, “ Why don’t you sign the awful paper? I am Jewish, but you don’t have any Jewish blood in you?”

“Come, now, Marianne,” Anna said, “would you have Constanze do anything that gives support to the evil notion that there is something wrong with having Jewish blood?”

Marianne stirred herself to an upright position at the end of the sofa. “I am a Jew.” Immediately, she looked unsure of herself.

Constanze didn’t miss a beat. “I am a Red.”

Anna was quick to chime in. “I am a Habsburger.”

Karl laughed as he said, “I am a police inspector.”

They all laughed. There was nothing else to do but laugh. They laughed joyful laughter that bound together the four Guest-Friends.