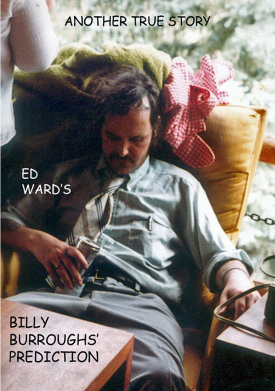

Billy Burroughs' Prediction

Edwin Ward

We meet, Billy Burroughs and I, at Steve Wilson and Larry Lake’s BOWERY BOOKS on Old South Pearl Street in Denver.

I am hanging out with Larry even though conflict between journeyman and apprentice flavors our friendship. As there is in the world, there is tension in our relationship for many reasons. The Seventies have ended. The Beats have been lionized, canonized and beatified while Hippies have been written off as “children who stayed too long at the party.” In the world that hasn’t tuned in, turned on, and dropped out, greed grows like a weed in the garden that once was America.

Larry and I are discussing the literary merit of his Nineteen Seventy-one small press magazine forte Mano-Mano 2 which lies open to pages thirteen and fourteen on the glass counter top of his display case. We’re both rereading the printed facsimile of the Neal Cassady to Justin Brierly letter wherein the incarcerated Neal writes from the Colorado State Reformatory in Buena Vista to his former probation officer and friend in Denver and asks Justin to pay a small overdue bar tab at a Platte Street saloon.

Currently the home of Brothers Bar, the site is one of the better hot spots serving food to waiters and waitresses getting off work late night in Denver. Hence, my familiarity with the place. Legendary and rightly so are the jalapeno cheeseburgers served there. As it so happens, Brothers Bar is one of numerous establishments from which Larry Lake, himself, is currently eighty-six-ed, mostly for reasons of art and alcohol, anger and disrespect. Larry once lived across Fifteenth Street, catty corner from Brothers, where he transformed an empty warehouse loft into a noteworthy second story walk-up art gallery and bohemian crib. The grand opening of his Bowery Gallery is the subject of an early Seventies’ independent film, entitled The Bowery Gallery. Despite Larry’s artistic infamy and fame, and his dogged ability to attract media attention, for more than one reason, all unknown to me, Larry and the two brothers who own Brothers Bar, they had a tumble of mythic proportions some time back, the facts and fictions of which I only know as rumor. It’s odd-ball ironic that a page torn from Larry’s magazine, to this day, lends notoriety to a place Larry’s not allowed to enter! Next to the pay phone in the back hangs page twelve from Larry’s Mano-Mano 2, a shard of beat debris, something the brothers who banished Larry cherish.

I am confessing to Larry that I’m mostly ignorant of Neal’s stature and importance in the literary world. Because Jack Kerouac and the antics of his anti-hero, Dean Moriarty, were neither part of my Jesuit high school curriculum nor on the reading lists of generously loaning, book buying friends, I only know of Neal Cassady as the driver of the bus FURTHER in Ken Kesey’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, a text my old girlfriend M laid on me. Believe it or not, just as I’m saying the words Neal Cassady, into the storefront bookshop walk two of Neal Cassady’s real life existential pals: his own legendary partner in beatitude and pop culture myth, the eminent poet, Allen Ginsberg, (who, as it turns out, happens to be William S. Burroughs Jr.’s not so unlikely godfather); and the author of Speed and Kentucky Ham, himself, William S. Burroughs Jr., Billy B. As a gesture of goodwill and friendship towards and kinship with Larry and Steve, Allen has come to Bowery Books to autograph some first editions thereby increasing the value of Bowery Books’ Beat literature collection, and Allen is giving Billy, who has moved here to Denver, Allen’s version of the Poetry Tour of Denver.

When Allen Ginsberg introduces William S. Burroughs, Jr. to Larry Lake and me, the reader/writer/junkie in Larry immediately recognizes the reader/writer/junkie in Billy, and, thus, the proprietor of Bowery Books and the publisher of Bowery Press, Larry Lake, he turns on the charm for his celebrated guests. For the next hour Larry and Allen banter and gossip tales of mutual friends: Stuart Zane Perkoff and James Ryan Morris, Diane Di Prima and Robert Creeley, Tony Scibella and David Meltzer, while Billy B and I, we mostly listen.

And naturally, or as this story will demonstrate, preternaturally, Billy likewise recognizes the

kindredness between himself and Larry; and when Larry suggests that Billy should sometime read something from his novels at Café Nepenthes, the poetry reading that Marcia and I host in lower downtown Denver, Billy, who is known to demand big bucks for a reading, accepts, all without discussing payment. I figure he’s hoping to score in terms of reading material, turn-ons and connections.

Over the course of the next year or so I pursue a friendship with the creature that is Billy Burroughs. I say creature, because not unlike Frankenstein, Billy B, he’s come back from the dead. Another’s liver keeps him alive, that of a woman named Virginia whose brain failed at about the same time that Billy’s original liver did.

Billy lives at the Oxford Arms, one of a pair of sixteen-plex apartments just south of University Hospital on the east side of Colorado Boulevard. On Number Sixteen, his door, is a handwritten announcement that emphatically states “If you’re not from Boulder, you’re NOT WELCOME. Go Home. This means YOU!” When I read the admonition for the first time, I’m annoyed, wondering if I’m to be dismissed as not from Boulder, for from what I’ve learned from my study of modern American poetics,

Denver, my adopted hometown, is, in fact, the birthplace of beat sensibility. I even have an un-redacted copy of a letter to Ed White that I got from Larry in which Jack Kerouac, himself, does declare the rank of Denver’s own Neal Cassady’s writing to be among the greatest of America and modern Europe.

Billy’s furnished apartment is as messy and muddled as is his health. A couch lines the south wall out of the center of which sticks the non-business end of a bayonet, the blade buried to the hilt in the cotton stuffing with its tip in the wall behind. Above the couch is an assemblage of magazine photo cutouts. Now the number of cigarette burn holes in the seat of the couch is alarming, given the number of people who live in this building. One generally doesn’t consider the possible carelessness of others when signing a lease, and the burn holes spell jeopardy and danger. On the stove sits a stew that never really runs out as Billy B adds to it whatever edibles he has on hand. When I lift the lid I am reminded more of slurry sludge than food. Whatever vegetables might have been in the mix have over time and reheating been reduced to mush. Even the remains of a hot dog that Billy claims to have added just yesterday seem about to liquefy. Needless to say, neither my ex Italian mother-in-law or my current German mother-in-law would be caught dead in Billy’s kitchen. Skieve!, Filth! would be their refrains.

Billy and I, we do literary events together, and Billy, per the arrangement we made the day we met, does read at Café Nepenthes, my current Tuesday night Market Street gig. I collect twenty when I pass the hat and add thirty myself so Billy’s pay turns out to be a cool fifty bucks for a half hour’s reading.

Better pay than my lawyer’s, I remark when I hand him the cash.

Immediately after his feature reading, I take Billy home to his apartment as he has scant interest in the late night world I revel in, and he has no interest in the poets and poet tasters who attend. And, granted, my waiter’s hours are not sympatico with his pain relief schedule. I drive him in my Dodge Tradesman van a couple of times to Naropa Institute in Boulder to visit Allen Ginsberg and other visiting literary luminaries. He seems to enjoy the attention the Naropa-ites, students and teachers alike, shower upon him. After all, he is no literary slacker. He’s already had two novels published and sundry articles in national magazines including one in Time about the abusive superintendent of a juvenile facility in Florida.

On subsequent visits to Billy’s apartment, he reads to me some very poignant and humorous short stories about his stay in the hospital post-surgery, about wandering the corridors and deep basements in the wee hours of hospital late shifts, running once into a wide-eyed, burned-black crispy corpse on an elevator gurney, and often into over-medicated maintenance staff in restricted areas.

Despite the humor of his intellect as demonstrated in his writing, if truth be told, Billy is, for the most part, a sad sack. He knows the new lease on life he’s been given is a short-term lease, no matter the star status of his South African transplant of a transplant surgeon, Doctor Starzl. He is so medicated both from the morphine he injects for the pain of the arthritis that came with the transplant and from the excessive alcohol - Schmidt’s Malt Liquor, please - and from the steroids he takes to ward off organ rejection (Billy once told me: If I look at a cold, I catch it) . . . Billy is so medicated that he’s mostly a man on the nod. He spends much of his time in an overstuffed chair. Alice in Wonderland is the theme of a collage he has affixed to the wall opposite his chair.

On a couple of occasions I accompany Billy to a an apartment north of University Hospital on

the west side of Colorado where an assemblage of hospital junkies gathers to swap pills, drink beer, and generally banter with each other like addicts at an NA meeting telling drug stories, except these attendees are not on the wagon, are not taking thirteen steps towards sobriety and abstinence. In the middle of the living room, the lessees - Ernie and Ray, two Viet Nam veterans with serious problems related to the draft, their military service and exposure to Agent Orange - have placed a thirty gallon plastic trash can. It is filled with empty alcohol bottles, crushed cigarette packs, and the debris of fast food existence. Most attendees at the daily medication exchange rarely rise to pitch their empty long necks, Coors cans, and hamburger wrappers, into it, like basketballs into hoops, from their surrounding lawn chair seats The occasional marijuana contributed to the get-together is most welcome as cannabis is not something prescribed across the street at University Hospital, where the drugs being swapped originate. Of course, Billy does not offer to barter with his morphine, only some of the minor barbiturates he’s been prescribed. Around the circle I note some curious exchange rates: five Valium for one Thorazine, a carton of Camels for one Dilaudin.

But there’s more to Billy B than drugs and despair, more than woe is pitiful me. For Billy B, he is a gentleman and a scholar. Billy B has died and been born again, not in a Born Again Christian sort of way, but rather in a born again beatnik sort of way. He writes beautiful poems on scarps of Safeway paper bags, and he seems to possess a special gift, a heightened intuitive sense, that, as this story will demonstrate, is downright spooky. His harsh comments about the state of our great nation are painfully true. His discontent and disgust, his despair and disrespect, are based on experience, not politics. Yet hidden amongst the unkempt and sometimes bitter persona that Billy B shows the world, there resides a spirit more angelic than demonic. Perhaps Billy got more than just a liver from his donor, Virginia, for there are otherworldly qualities to Billy, as if all the pain and medication and fear have parted the veil betwixt now and forever. On occasion Billy sometimes sports a trickster smile in the shadow of his derby hat that even seems to enlighten the darkened corners of Ernie and Ray’s misaligned minds.

Sooooo anyway, I throw a birthday dinner party for Billy, his thirty-third and last. In attendance at my house on South Pearl are Billy, his drug swap buddies, Ernie and Ray, Larry Lake and his new bride Barbara, entrepreneurial bakers Marie and Melvin Neumann (who bring beautifully braided rye and wheat loafs to the celebration), the artist Kelley Simms, best man at my wedding, Lenny Chernila, the poet Andy Clausen, myself and my wife Marcia. The menu is East Coast Italian: antipasto, Caesar salad, sausage and spaghetti with a scratch Marinara sauce. The birthday cake is an over the top, incredibly rich, New York cheesecake, (the secret recipe for which I received as a wedding present from friends of my first wife’s parents. In fact, when my first marriage hit the rocks, I jumped ship with only it, the secret recipe, to face the future with. I used to sell slices of it for a buck at street fairs, a price far below its value; and when satisfied customers, commenting on its superior qualities, would say that I ought to sell it for more, I’d make it known the secret recipe was available for ten; and I’d make a princely profit on the sale of Xerox-ed recipes.)

Anyway, after Billy blows out the thirty-three candles that yin-yang atop his birthday cake, there are good wishes wished and toasts toasted to a future that proves shorter and bleaker than anyone but Billy might have guessed. And then, after a pause, Billy, with stoned eyes a sparkling, makes a prediction, prognosticating with a question directed at Marcia.

“So when are you going to make your big announcement?”

Marcia blushes a bit and stares at her questioner imploringly, as, apparently, she has no idea what Billy’s talking about, and says so.

“Ah, come on, he continues, tell us about it.”

“Tell you what? I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

Billy sighs, smiles, and rephrases his request. “When are you going to tell us about the baby?”

Somewhat alarmed, yet with a mixture of naughty delight and hopeful anticipation, while simultaneously defensive, Marcia soundly refutes the thrust of Billy’s innuendo.

“I most certainly am not pregnant.”

Billy sighs again, smiles again, and adds, “Ah yes, so you think, but nonetheless, you are. I would never kid about something like this. Being pregnant is not funny. Believe me. You are going to have a baby.”

The next day, bothered yet excited by Billy’s prediction, Marcia buys an early pregnancy test, and sure enough: she’s pregnant. I guess we were not as careful as usual the night of Tommy Larkin’s marriage. Too much wine and too much passion will do that to young lovers at an Irish Catholic wedding.

Sadly, the following March, some three weeks before the birth of my first son, Passion, Billy dies. The story I hear is that after Ronald Reagan’s inauguration in January of Nineteen Eighty-one, the new president’s first Presidential Directive, his first volley in his War on Drugs, is to forbid the use of morphine for out-patients, a directive that greatly affects Billy and his pain relief. Denied his out patient morphine regimen - one he’s grown totally addicted to - Billy opts to split Denver and return to Florida where he’d spent some happy days prior to his liver failure and transplant. The urban myth is that on the twenty-five hundred mile bus ride from Denver to Gainsville, Billy looks at a cold and catches it, a cold that, within short order, kills him, demonstrative proof that a mix of steroids and viruses can be lethal.

Doing the backwards math, Marcia and I figure that she had been a mere thirteen days pregnant when Billy made his prediction, demonstrative proof of Billy’s special gift, of his intuitive ability to read others, their condition, and their future, a trait he once told me his grandmother had divined in him. Too bad Billy B never met my son, the proof of his prediction.