Lefty Takes a Turn

Cy Hill

The pockmarked wooden booth was painted black.

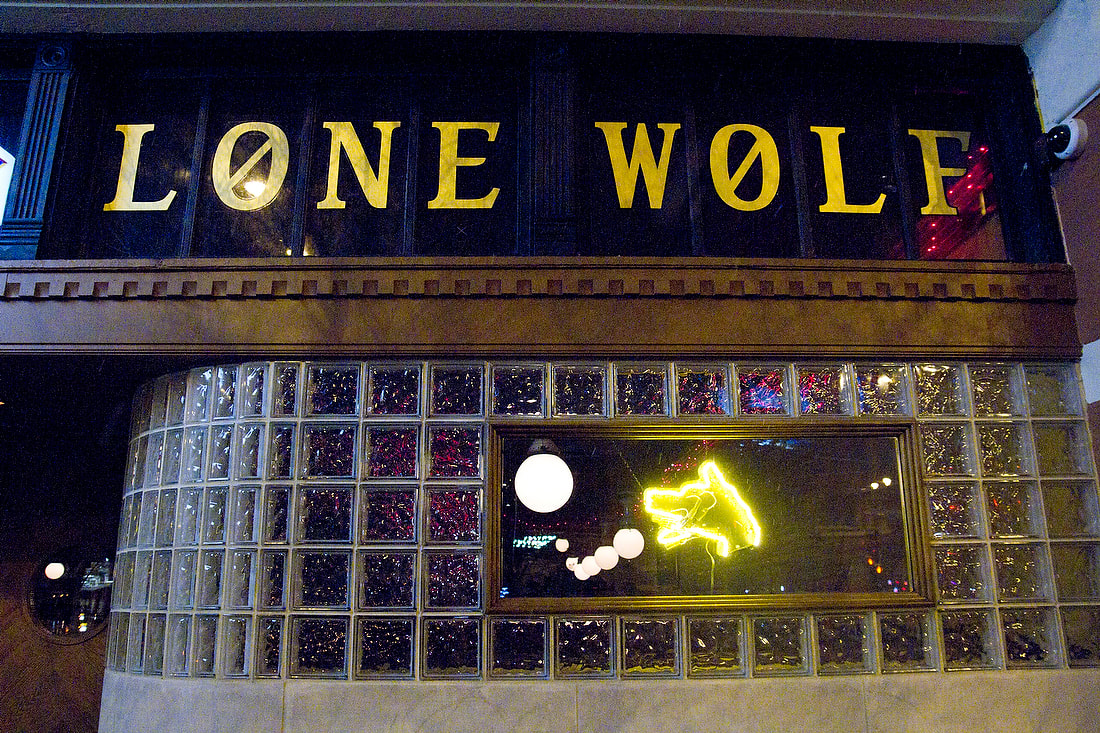

Lefty listened to the rain ping off the long Lone Wolf Tavern window fronting Forty-fifth Street, his right cheek laid on a hardwood table next to half a pitcher of beer. A large safety pin transfixed the blue cloth of his long sleeve shirt into a neat fold three inches beneath his right shoulder. The rest of his right arm was in Viet Nam. Five-plus-years had passed since the medic cut it off, but in his reckoning of time, the amputation and all that came with it happened yesterday.

Today was his twenty-fifth birthday. It was not going well. A woman at another bar called him a baby killer and said that he should have left the rest of himself in Viet Nam. That closed his time out at that bar. He was low on cash so he drove to his apartment and saw the red blink of a message left on his answering machine. His mother and father bequeathed flaccid obligatory birthday wishes. They hoped he was doing well in Seattle, but he knew they were relieved to have him so many miles from Tulsa. It shadowed their words. Because of his moods. His family was tired of him, he wore them out: their battle fatigue. They said that he had changed. Imagine that. He knew they half-expected him to just get on with it and kill himself.

Standing before Lefty, carrying his own beer glass and headed for the deeper recesses of the tavern, Shakey John paused and half-waved; tilted his head to the side to line it up with Lefty’s, to make solid eye contact in the dark place. Longhaired Shakey drove his own cab and was dressed dapperly in post-hippy modern, with corduroy vest, strung circle-watch and chain, and a tweed Yorkshire driving cap.

“Is all well in Lefty world?”

Lefty blinked, communicating the affirmative. Shakey nodded, smiled, touched the brim of his with an index finger, and moved on.

Initially Lefty hated this place that did not pretend to be anything but a dive. He did not know why he kept coming back. No one called him “Lefty”, not to his face -- until he walked in here, and here, everyone called him Lefty. The saving grace was that everyone knew his past and nobody gave a shit. For some reason his sober self could not understand, by day’s end this was where he always crash-landed.

Seven years ago, given his disastrous draft number in the lottery based upon his birthday – this day – it was either get a college deferment, or hello Army. He never liked school, and his family and peers were proud to see him go in, put on that uniform, receive Infantry Radioman training, and go out and protect America. Then he came back. He squandered his G.I. education money, flunking out of classes he did not care about. He supported himself with his disability check and a series of jobs he did not care about. At the request of his family, the VA tried to keep tabs on him, but they were overwhelmed with veterans who were willing to ask for assistance.

Lefty sat up, dumped what was left of his pitcher into his beer glass, and drank it as fast as he could. He wanted to get drunk on his twenty-fifth birthday, rip-roaring, angrily poetic, potentially destructive drunk. Unfortunately, to get that drunk required hard liquor, and when he drank spirits of significant proof, his body occasionally ambushed him with the sudden surprise of explosive diarrhea. He could never go back to those bars again. Nor could he return to those where he had let slip that he lost his arm not due to enemy ordnance, but an infected monkey bite.”

He put his cheek back down on the scarred varnished surface. Someone entered the bar, and a fresh hard underhand of cool damp breeze swept in, braining him with stale cigar and cigarette smoke, and flat spilt beer. The rhythm of the rain accelerated against the window.

Tom Waits’ “Nighthawks at the Diner” suddenly came on over the tinny speakers via CD cassette. It was the bartender’s job to keep the music coming, but Boom Boom frequently forgot. He preferred to keep a local FM radio station on for music, but something had gone wrong and he did not know how to fix it.

“Hi, Lefty.” Gloria, a substitute teacher and sometimes travel agent, stopped before him holding her beer glass. She had wheedled much of his life story out of him over months of late-night drinking, even the embarrassing things. She observed him as a thing of curiosity, but he was not offended. It was the way she looked at everyone, and she was not judgmental. She had her own problems. Like her hair. It looked like squirrels were hiding nuts in it.

Beside her was Rosalind, a Biology teacher. She wore a pin of an Anchiornis huxley, a long extinct red-headed feathered dinosaur about the size of a crow and a link in the evolutionary chain that connected dinosaurs to birds. Rosalind was one of the smartest people he had ever met. From his description of the monkey that bit him and the approximate geographic location of their encounter, she was able to tell him which species it probably was. He kept meaning to stop by a library to see if she was right. Like him, Rosalind had difficulty holding onto a job. His problem was that he did not care. Hers was that she cared too much. She had a mindset too scientific to teach science in public school, and a rich cursing vocabulary that exploded at inappropriate moments, the later a trait bequeathed by her father, a career navy Boiler Technician.

With Lefty’s head sideways on the thick wooden slab, the women were perpendicular to him. Both were about thirty. Both smiled at him. For some reason they liked him. Even though they knew him.

“Tough day?” Gloria asked.

He blinked once.

“If you want to put your head down on our table,” Rosalind offered, “we’re going to be back by the pool table.”

He blinked twice. They took that as a “yes” and moved on.

Wolfram, a loud West German philosophy graduate student at the University of Washington with a mane and moustache of golden hair, following Rosalind at what he thought was a subtle distance of pursuit, paused before him. “What!? Your glass is empty?

“Boom Boom!” he yelled at the owner-bartender, “this man is out of beer!”

“Then he can walk his ass up here and get it.” Boom Boom, whose hobby was bodybuilding, was anchored behind the long bar, opposite the long window that framed Forty-Fifth Street.

“Can’t you see how hard he is working here, holding your table down with his head? You need a barmaid!”

The first one of those Boom Boom hired, his first employee, he had to fire for supplementing her on-the-clock paycheck with hooking in a back booth. He was now gun-shy about hiring anyone.

“I hate to see an empty glass,” Wolfram filled Lefty’s from his own pitcher.

Lefty put his hand around the glass, lifted his head an inch off the table, and dropped it to indicate his thanks.

“You are welcome, Lefty,” Wolfram replied to the thud and patted him on the shoulder. He shifted his attention to Rosalind by the pool table, pretending to just notice her. “Rosalind! Is it true that all female Biologists are lesbians?” Everyone in the Lone Wolf but Rosalind knew that this was his inept way of courting her. She replied by calling him a pillock, a hobbledehoy, and asked if his moustache was a merkin, words the meaning of which only she knew, but everyone else laughed uproariously, as if they knew, too, agitating the already high-strung Wolfram to conclude that he was the only one who did not understand how he had just been insulted.

Lefty fermented. Eventually he sat up, chugged the beer Wolfram gave him, and put his head back down. No music again? Whatever Boom Boom’s problem was with connecting to the FM station, he knew that he could fix it. So why didn’t he? Lefty was just drunk enough for brain images to form, break apart, and become something new, all mixed with voices, words, emotions. One solidified thought was that Seattle was about the fourteenth city he had been through since his discharge and maybe it was time to move on again.

Jethro Tull’s “Stormwatch” came on.

He had to use the bathroom. That meant that he had to get up. Rather than go the short way, past the crowded pool table and all its sexual banter and the people who might want to speak with him, he went the other way around, past the long bar, towards the lone entry to the street at the end of it, and then back past the less frequented booths to the restroom.

“Lefty. You want another pitcher?” Balding Boom Boom called from behind the bar.

Lefty waved him off.

In one of the dark booths, he saw Sim, glasses perched on the end of his nose, a faded porkpie hat raked over his forehead. Beside him was the briefcase. Sim sold drugs; all kinds, he was a traveling pharmacy, no doubt conducting business in out of the rain and certainly without Boom Boom’s knowledge. A few booths back a man sat with a heavy blue checked overcoat across his lap. It covered the head and upper torso but not the bluejeaned hips, legs, and signature lavender tennis shoes of Gwen, the former Lone Wolf barmaid. She was practicing her trade. If a policeman walked in and saw this, he would shut The Lone Wolf down. It had happened before. This tavern was the least favorite in the University district of all Seattle City officials. Lefty took a right, and then a quick turn into the Men’s Room.

There were three urinals. Above the first one, someone had scribbled, “To Do is to Be. Plato”, over the second one, “To Be is to Do. Aristotle”. “Scooby dooby do. Frank Sinatra”, was scrawled over the third. As all three urinals were of the same height and the enamel democratically cracked and stained, Lefty was never particular as to which one he used. However tonight, sprawled across the tile, passed out drunk, denying access to all three, was a whale of a man with a yellow t-shirt riding up above his hairy navel that read “Dare to Be Stupid”. Vomit covered the urinals, the wall in between them, and the tile upon which the man lay. He snored.

Lefty stepped out of the Men’s Room and saw Shakey John stepping in from the alley. “What can you do?” Shakey asked, zipping up his corduroy fly.

Lefty reopened the emergency escape fire door which incorrectly warned not to open it or an alarm would go off, kicked over a brick to hold it open, and stepped out into the raw cold freshness of rainfall striking head and shoulders from above, and splashing up off the pavement below onto his shoes and jeans’ cuffs. Happy 25th Birthday, Lefty.

As his liquid past ripped out of him, he groggily took in his surroundings. That was his car, forty feet distant. The area behind the tavern was unregulated, and those who knew parked here. He wished that he could see the stars, somehow all would have been better, less bitter, if he could only see the stars. There were times when he had those same thoughts in Nam.

Something skittered across from him. A rat traversed the glistening asphalt, pastels reflected across its damp screen, and there was a small something in its mouth, a small something that was – or had been – alive.

From his right, a plaintive cry. Such pain, such pain as only the suffering living can emit. Beneath the dumpster was a feral cat, wedged up in cardboard, water and filth dripping, with a fresh litter. It was one of those newborns the rat held in its mouth. And even as he watched, another was snatched away, by an eight-inch-long rat. She had but three kittens left.

Lefty went to his car. He had a .25 Colt pistol that he used for target practice. He was a good shot. As he returned to the sodden cardboard creche, but two newborn kittens remained, and a rat hovered above the litter, ready to take another. One shot stuck it against the bricks. Its dying eyes, red from within, or from the smear of filthy rain and fragmented greasy asphalt -- who knew -- but it seemed to ask, “Why? What did I do to you? I had young ones to feed. Now they will be another’s food.”

After his spontaneous action, spontaneous decision about what lived and what died -- who was he? What right had he to make such decisions, about life and death -- and what did it even matter? What did he matter? To anyone, even to himself? He put the weapon to his temple. His blood, his bones, his body could feed the rats, feed the cat and her kittens, feed the crows –

Red eyes; another rat, ready to leap and snatch another kitten, poised to strike from beneath the dumpster. Rather than put the bullet into his own head, where it would have crashed around, scattering all his memories, his personality, whatever it was that he was – he did that to the rat. Lefty did not think about it, his body made the choice, the decision, for him. It wanted to live, however his mind felt about it. He lacked a right arm? So what? The monkey that bit him was trapped in a snare, and he freed it. His squad’s medic was dead, they were fighting for their lives, and it was not until they hooked up with another squad days later, likewise decimated by enemy fire, that their medic tried to save his arm but could not; finally taking it off three inches beneath the shoulder because they could not get a helicopter in to take him out. How many American soldiers; how many Vietnamese men, women, and children had he seen, freshly slaughtered; or bloated in death; or their feasted upon remains? And he was now arbitrating life and death between the wild things in an alley?

This mother cat gave birth to kittens because that was what female cats do. A rat saw them as food for herself and her young. Who was right, who was wrong, and was not the very question ridiculously naïve? In the end, all that it was about was survival, and you did what you had to, to survive; or you did not.

No one was owed anything.

As he watched, the rats that he had killed were carried off by other rats. Food had been provided. Deus ex Machina, he remembered that from somewhere. He was the god from nowhere that provided deliverance, however temporary, to the mother cat and her two young, to the hungry rodents who would now feast upon their own.

The mother cat hissed at him.

He considered shooting her, too. He could. What difference would it make? Ultimately? The Universe moved on. The rain fell. What made a difference? What even mattered? He could kill himself, but so what? Yeah, Lefty, put a bullet in your head. So what? Who cared? Who could possibly care if you did? And who would care if you did not?

It was time to make a decision.

All of this around him, the quick and the dead, the .25 in his left hand, a mother’s meow and a rat’s carcass feeding another rat’s offspring, this was life, life in death, the vagaries of every conscious moment.

“To be is to do.” “To do is to be.” “Scooby dooby do.” The truth was written broad on the Lone Wolf’s Men’s Room wall over three urinals, he had read it so many times, but he did not understand it until now.

He shoved the Colt in his back pocket and confronted Boom Boom across the bar.

“Someone I have never seen before has thrown up and is passed out in the Men’s Room.”

“Yeah,” Boom Boom said, wiping down the bar, “you are probably the sixth person to tell me that. What am I supposed to do, I can’t leave the bar – “

“I will clean it up.”

Boom Boom focused upon the one-armed man. He was different. “Why? Why will you clean it up?”

“Because it needs to be done. Sim is sitting in the back with his briefcase.”

“What?! I banned him from ever coming in here again --!”

“Gwen is working a couple of booths behind him.”

“God damn it!” He threw down his bar rag.

“I’ll take care of it.”

Boom Boom was willing to bargain. It would take him at least five minutes to secure everything behind the bar to go back there himself. “I’ll pay you in beer.”

Lefty shook his head. “I will do it because it needs to be done.”

He recruited Shakey John to grab one leg of the drunk passed out in the Men’s Room while he grabbed the other. They dragged the heavy man out into the alley and left him beside the dumpster to shield the feral cat and her two remaining kittens. His snoring life now had a purpose.

He stuck his .25 into Sim’s neck and said, “Boom Boom told you the nice way to never come in here again. This is as nice as I get. Exit through the front door, and on the way out, don’t let the doorknob hit you where the good Lord split you.” Sim did as he was told.

Long-necked Gwen was still under the same booth table practicing her trade, but working on a different customer wearing work boots. Lefty grabbed an ankle, pulled her out from under the table, and kicked her blue-jeaned ass hard in the direction of the front door. She cursed him until she saw the glow in his eyes. Then, she ran for the door. Lefty turned to the booth to do the same to her customer, but he was gone.

He returned to the Men’s Room, cleaned up the vomit, and mopped the tile. Then, he gave the Lady’s Room a once over. As he worked, sweating the alcohol out of his pores, his mind concluded that his body was smarter than it was. It was his body that had made all of the correct decisions since he stepped out into the alley, independent of his conscious mind.

“I have no idea what got into him,” Shakey John was telling Boom Boom when Lefty arrived at the long bar to ask what he could do next.

“I don’t know how much I can pay you,” Boom Boom cautioned, “but you’ve got the job. You are only the second person I have ever hired, so we’ll have to figure this out. Come on back here, behind the bar.”

Lefty ducked under the waist-high wooden slat and came up within the sanctity of the barkeep’s arena of cash register, tapped kegs, bottled wine, pickled eggs, pigs’ feet, Slim Jim’s, and a rack of packaged Frito Lay products.

“I can fix your FM connection,” he said, “so we can get that radio music station back.”

Cy Hill

The pockmarked wooden booth was painted black.

Lefty listened to the rain ping off the long Lone Wolf Tavern window fronting Forty-fifth Street, his right cheek laid on a hardwood table next to half a pitcher of beer. A large safety pin transfixed the blue cloth of his long sleeve shirt into a neat fold three inches beneath his right shoulder. The rest of his right arm was in Viet Nam. Five-plus-years had passed since the medic cut it off, but in his reckoning of time, the amputation and all that came with it happened yesterday.

Today was his twenty-fifth birthday. It was not going well. A woman at another bar called him a baby killer and said that he should have left the rest of himself in Viet Nam. That closed his time out at that bar. He was low on cash so he drove to his apartment and saw the red blink of a message left on his answering machine. His mother and father bequeathed flaccid obligatory birthday wishes. They hoped he was doing well in Seattle, but he knew they were relieved to have him so many miles from Tulsa. It shadowed their words. Because of his moods. His family was tired of him, he wore them out: their battle fatigue. They said that he had changed. Imagine that. He knew they half-expected him to just get on with it and kill himself.

Standing before Lefty, carrying his own beer glass and headed for the deeper recesses of the tavern, Shakey John paused and half-waved; tilted his head to the side to line it up with Lefty’s, to make solid eye contact in the dark place. Longhaired Shakey drove his own cab and was dressed dapperly in post-hippy modern, with corduroy vest, strung circle-watch and chain, and a tweed Yorkshire driving cap.

“Is all well in Lefty world?”

Lefty blinked, communicating the affirmative. Shakey nodded, smiled, touched the brim of his with an index finger, and moved on.

Initially Lefty hated this place that did not pretend to be anything but a dive. He did not know why he kept coming back. No one called him “Lefty”, not to his face -- until he walked in here, and here, everyone called him Lefty. The saving grace was that everyone knew his past and nobody gave a shit. For some reason his sober self could not understand, by day’s end this was where he always crash-landed.

Seven years ago, given his disastrous draft number in the lottery based upon his birthday – this day – it was either get a college deferment, or hello Army. He never liked school, and his family and peers were proud to see him go in, put on that uniform, receive Infantry Radioman training, and go out and protect America. Then he came back. He squandered his G.I. education money, flunking out of classes he did not care about. He supported himself with his disability check and a series of jobs he did not care about. At the request of his family, the VA tried to keep tabs on him, but they were overwhelmed with veterans who were willing to ask for assistance.

Lefty sat up, dumped what was left of his pitcher into his beer glass, and drank it as fast as he could. He wanted to get drunk on his twenty-fifth birthday, rip-roaring, angrily poetic, potentially destructive drunk. Unfortunately, to get that drunk required hard liquor, and when he drank spirits of significant proof, his body occasionally ambushed him with the sudden surprise of explosive diarrhea. He could never go back to those bars again. Nor could he return to those where he had let slip that he lost his arm not due to enemy ordnance, but an infected monkey bite.”

He put his cheek back down on the scarred varnished surface. Someone entered the bar, and a fresh hard underhand of cool damp breeze swept in, braining him with stale cigar and cigarette smoke, and flat spilt beer. The rhythm of the rain accelerated against the window.

Tom Waits’ “Nighthawks at the Diner” suddenly came on over the tinny speakers via CD cassette. It was the bartender’s job to keep the music coming, but Boom Boom frequently forgot. He preferred to keep a local FM radio station on for music, but something had gone wrong and he did not know how to fix it.

“Hi, Lefty.” Gloria, a substitute teacher and sometimes travel agent, stopped before him holding her beer glass. She had wheedled much of his life story out of him over months of late-night drinking, even the embarrassing things. She observed him as a thing of curiosity, but he was not offended. It was the way she looked at everyone, and she was not judgmental. She had her own problems. Like her hair. It looked like squirrels were hiding nuts in it.

Beside her was Rosalind, a Biology teacher. She wore a pin of an Anchiornis huxley, a long extinct red-headed feathered dinosaur about the size of a crow and a link in the evolutionary chain that connected dinosaurs to birds. Rosalind was one of the smartest people he had ever met. From his description of the monkey that bit him and the approximate geographic location of their encounter, she was able to tell him which species it probably was. He kept meaning to stop by a library to see if she was right. Like him, Rosalind had difficulty holding onto a job. His problem was that he did not care. Hers was that she cared too much. She had a mindset too scientific to teach science in public school, and a rich cursing vocabulary that exploded at inappropriate moments, the later a trait bequeathed by her father, a career navy Boiler Technician.

With Lefty’s head sideways on the thick wooden slab, the women were perpendicular to him. Both were about thirty. Both smiled at him. For some reason they liked him. Even though they knew him.

“Tough day?” Gloria asked.

He blinked once.

“If you want to put your head down on our table,” Rosalind offered, “we’re going to be back by the pool table.”

He blinked twice. They took that as a “yes” and moved on.

Wolfram, a loud West German philosophy graduate student at the University of Washington with a mane and moustache of golden hair, following Rosalind at what he thought was a subtle distance of pursuit, paused before him. “What!? Your glass is empty?

“Boom Boom!” he yelled at the owner-bartender, “this man is out of beer!”

“Then he can walk his ass up here and get it.” Boom Boom, whose hobby was bodybuilding, was anchored behind the long bar, opposite the long window that framed Forty-Fifth Street.

“Can’t you see how hard he is working here, holding your table down with his head? You need a barmaid!”

The first one of those Boom Boom hired, his first employee, he had to fire for supplementing her on-the-clock paycheck with hooking in a back booth. He was now gun-shy about hiring anyone.

“I hate to see an empty glass,” Wolfram filled Lefty’s from his own pitcher.

Lefty put his hand around the glass, lifted his head an inch off the table, and dropped it to indicate his thanks.

“You are welcome, Lefty,” Wolfram replied to the thud and patted him on the shoulder. He shifted his attention to Rosalind by the pool table, pretending to just notice her. “Rosalind! Is it true that all female Biologists are lesbians?” Everyone in the Lone Wolf but Rosalind knew that this was his inept way of courting her. She replied by calling him a pillock, a hobbledehoy, and asked if his moustache was a merkin, words the meaning of which only she knew, but everyone else laughed uproariously, as if they knew, too, agitating the already high-strung Wolfram to conclude that he was the only one who did not understand how he had just been insulted.

Lefty fermented. Eventually he sat up, chugged the beer Wolfram gave him, and put his head back down. No music again? Whatever Boom Boom’s problem was with connecting to the FM station, he knew that he could fix it. So why didn’t he? Lefty was just drunk enough for brain images to form, break apart, and become something new, all mixed with voices, words, emotions. One solidified thought was that Seattle was about the fourteenth city he had been through since his discharge and maybe it was time to move on again.

Jethro Tull’s “Stormwatch” came on.

He had to use the bathroom. That meant that he had to get up. Rather than go the short way, past the crowded pool table and all its sexual banter and the people who might want to speak with him, he went the other way around, past the long bar, towards the lone entry to the street at the end of it, and then back past the less frequented booths to the restroom.

“Lefty. You want another pitcher?” Balding Boom Boom called from behind the bar.

Lefty waved him off.

In one of the dark booths, he saw Sim, glasses perched on the end of his nose, a faded porkpie hat raked over his forehead. Beside him was the briefcase. Sim sold drugs; all kinds, he was a traveling pharmacy, no doubt conducting business in out of the rain and certainly without Boom Boom’s knowledge. A few booths back a man sat with a heavy blue checked overcoat across his lap. It covered the head and upper torso but not the bluejeaned hips, legs, and signature lavender tennis shoes of Gwen, the former Lone Wolf barmaid. She was practicing her trade. If a policeman walked in and saw this, he would shut The Lone Wolf down. It had happened before. This tavern was the least favorite in the University district of all Seattle City officials. Lefty took a right, and then a quick turn into the Men’s Room.

There were three urinals. Above the first one, someone had scribbled, “To Do is to Be. Plato”, over the second one, “To Be is to Do. Aristotle”. “Scooby dooby do. Frank Sinatra”, was scrawled over the third. As all three urinals were of the same height and the enamel democratically cracked and stained, Lefty was never particular as to which one he used. However tonight, sprawled across the tile, passed out drunk, denying access to all three, was a whale of a man with a yellow t-shirt riding up above his hairy navel that read “Dare to Be Stupid”. Vomit covered the urinals, the wall in between them, and the tile upon which the man lay. He snored.

Lefty stepped out of the Men’s Room and saw Shakey John stepping in from the alley. “What can you do?” Shakey asked, zipping up his corduroy fly.

Lefty reopened the emergency escape fire door which incorrectly warned not to open it or an alarm would go off, kicked over a brick to hold it open, and stepped out into the raw cold freshness of rainfall striking head and shoulders from above, and splashing up off the pavement below onto his shoes and jeans’ cuffs. Happy 25th Birthday, Lefty.

As his liquid past ripped out of him, he groggily took in his surroundings. That was his car, forty feet distant. The area behind the tavern was unregulated, and those who knew parked here. He wished that he could see the stars, somehow all would have been better, less bitter, if he could only see the stars. There were times when he had those same thoughts in Nam.

Something skittered across from him. A rat traversed the glistening asphalt, pastels reflected across its damp screen, and there was a small something in its mouth, a small something that was – or had been – alive.

From his right, a plaintive cry. Such pain, such pain as only the suffering living can emit. Beneath the dumpster was a feral cat, wedged up in cardboard, water and filth dripping, with a fresh litter. It was one of those newborns the rat held in its mouth. And even as he watched, another was snatched away, by an eight-inch-long rat. She had but three kittens left.

Lefty went to his car. He had a .25 Colt pistol that he used for target practice. He was a good shot. As he returned to the sodden cardboard creche, but two newborn kittens remained, and a rat hovered above the litter, ready to take another. One shot stuck it against the bricks. Its dying eyes, red from within, or from the smear of filthy rain and fragmented greasy asphalt -- who knew -- but it seemed to ask, “Why? What did I do to you? I had young ones to feed. Now they will be another’s food.”

After his spontaneous action, spontaneous decision about what lived and what died -- who was he? What right had he to make such decisions, about life and death -- and what did it even matter? What did he matter? To anyone, even to himself? He put the weapon to his temple. His blood, his bones, his body could feed the rats, feed the cat and her kittens, feed the crows –

Red eyes; another rat, ready to leap and snatch another kitten, poised to strike from beneath the dumpster. Rather than put the bullet into his own head, where it would have crashed around, scattering all his memories, his personality, whatever it was that he was – he did that to the rat. Lefty did not think about it, his body made the choice, the decision, for him. It wanted to live, however his mind felt about it. He lacked a right arm? So what? The monkey that bit him was trapped in a snare, and he freed it. His squad’s medic was dead, they were fighting for their lives, and it was not until they hooked up with another squad days later, likewise decimated by enemy fire, that their medic tried to save his arm but could not; finally taking it off three inches beneath the shoulder because they could not get a helicopter in to take him out. How many American soldiers; how many Vietnamese men, women, and children had he seen, freshly slaughtered; or bloated in death; or their feasted upon remains? And he was now arbitrating life and death between the wild things in an alley?

This mother cat gave birth to kittens because that was what female cats do. A rat saw them as food for herself and her young. Who was right, who was wrong, and was not the very question ridiculously naïve? In the end, all that it was about was survival, and you did what you had to, to survive; or you did not.

No one was owed anything.

As he watched, the rats that he had killed were carried off by other rats. Food had been provided. Deus ex Machina, he remembered that from somewhere. He was the god from nowhere that provided deliverance, however temporary, to the mother cat and her two young, to the hungry rodents who would now feast upon their own.

The mother cat hissed at him.

He considered shooting her, too. He could. What difference would it make? Ultimately? The Universe moved on. The rain fell. What made a difference? What even mattered? He could kill himself, but so what? Yeah, Lefty, put a bullet in your head. So what? Who cared? Who could possibly care if you did? And who would care if you did not?

It was time to make a decision.

All of this around him, the quick and the dead, the .25 in his left hand, a mother’s meow and a rat’s carcass feeding another rat’s offspring, this was life, life in death, the vagaries of every conscious moment.

“To be is to do.” “To do is to be.” “Scooby dooby do.” The truth was written broad on the Lone Wolf’s Men’s Room wall over three urinals, he had read it so many times, but he did not understand it until now.

He shoved the Colt in his back pocket and confronted Boom Boom across the bar.

“Someone I have never seen before has thrown up and is passed out in the Men’s Room.”

“Yeah,” Boom Boom said, wiping down the bar, “you are probably the sixth person to tell me that. What am I supposed to do, I can’t leave the bar – “

“I will clean it up.”

Boom Boom focused upon the one-armed man. He was different. “Why? Why will you clean it up?”

“Because it needs to be done. Sim is sitting in the back with his briefcase.”

“What?! I banned him from ever coming in here again --!”

“Gwen is working a couple of booths behind him.”

“God damn it!” He threw down his bar rag.

“I’ll take care of it.”

Boom Boom was willing to bargain. It would take him at least five minutes to secure everything behind the bar to go back there himself. “I’ll pay you in beer.”

Lefty shook his head. “I will do it because it needs to be done.”

He recruited Shakey John to grab one leg of the drunk passed out in the Men’s Room while he grabbed the other. They dragged the heavy man out into the alley and left him beside the dumpster to shield the feral cat and her two remaining kittens. His snoring life now had a purpose.

He stuck his .25 into Sim’s neck and said, “Boom Boom told you the nice way to never come in here again. This is as nice as I get. Exit through the front door, and on the way out, don’t let the doorknob hit you where the good Lord split you.” Sim did as he was told.

Long-necked Gwen was still under the same booth table practicing her trade, but working on a different customer wearing work boots. Lefty grabbed an ankle, pulled her out from under the table, and kicked her blue-jeaned ass hard in the direction of the front door. She cursed him until she saw the glow in his eyes. Then, she ran for the door. Lefty turned to the booth to do the same to her customer, but he was gone.

He returned to the Men’s Room, cleaned up the vomit, and mopped the tile. Then, he gave the Lady’s Room a once over. As he worked, sweating the alcohol out of his pores, his mind concluded that his body was smarter than it was. It was his body that had made all of the correct decisions since he stepped out into the alley, independent of his conscious mind.

“I have no idea what got into him,” Shakey John was telling Boom Boom when Lefty arrived at the long bar to ask what he could do next.

“I don’t know how much I can pay you,” Boom Boom cautioned, “but you’ve got the job. You are only the second person I have ever hired, so we’ll have to figure this out. Come on back here, behind the bar.”

Lefty ducked under the waist-high wooden slat and came up within the sanctity of the barkeep’s arena of cash register, tapped kegs, bottled wine, pickled eggs, pigs’ feet, Slim Jim’s, and a rack of packaged Frito Lay products.

“I can fix your FM connection,” he said, “so we can get that radio music station back.”