Corpus Christi

Ricardo Federico

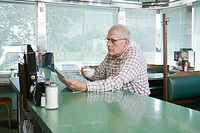

I can feel their eyes on me but I don’t look up. I’m sitting alone at the Waffle House counter, staring down into a cup of coffee with a cluster of coins piled in front of me. The older man puts a hand on his wife’s shoulder as they move past me to find a seat. They choose a booth on the other side of the room. The waitress, looking as tired and worn as her polyester uniform, comes over and refills my cup.

“Thanks,” I say.

“Sure thing,” she says, then flashes a perfunctory smile and moves on.

The grey sky sits heavy and low outside the windows and I’m in no hurry to leave. It’s cold out there and some of the chill has finally left my hands where I grasp the steaming cup. I start swirling it, watching the little vortex of coffee forming in the middle.

* * *

“Why not?” my wife Louise asked one bitterly cold night in Dayton as we pored over listing after listing on Internet realty sites. “I mean, we’ve waited all this time to enjoy life after work. Now it’s here.”

I was a month away from retiring after nearly four decades with the telephone company, and I was struggling with my wife’s proposition. But I had no solid argument against her logic, either. I rarely did. We had no children and only a few friends we could call close, but there really wasn’t anyone we couldn’t bear the thought of leaving. The truth was that we had waited a long time and now we wanted to do something for ourselves again.

Shortly after the retirement ceremony we drove to Florida to check out some of the places we’d seen on the Internet. We stayed for three days, walking through a dozen houses on the first two; the last day we saved for shopping, putt-putt golf and spontaneous stops for cold drinks or ice cream. This “fun day” was supposed to give us time to relax and let our minds process all the houses we had just walked through—time to think about all the pros and cons of each without the pressure of the realtor standing there. We were also treating ourselves and splurging like we hadn’t done for years, and it felt really good. Our plan was to talk about the houses on the drive back to Ohio and decide whether we should make an offer on any of them. But by the time we finished our complimentary hotel breakfast on the morning of our travel day, it was decided. In the end we sunk all our savings into a down payment on a brand new, two bedroom house—the brochure called it a ‘bungalow’—in an upscale Gulf Coast development called The Villa at Harborside. We would enjoy Harborside for five years, maybe ten, and then sell the place at a healthy profit. We had heard about quite a few couples who were doing the same thing and it seemed like a good plan.

* * *

The U-Haul sat in the driveway, nothing left in it but detritus from the move: a random coin or strip of packing tape, a few Styrofoam peanuts and a stack of haphazardly folded furniture pads. A huge star emblazoned on the truck’s side marked Corpus Christi on an outline of the Lone Star State.

“What are you doing?” I asked, closing the front door behind me. Louise was jetting across the room at her usual breakneck pace, a bundle of clothes draped in the crook of one arm.

“Unpacking, love. It’s the part that usually comes after you’ve packed everything and carried it to the new place.”

“Nobody likes a smart ass.”

“You wouldn’t know what to do without me.” Louise winked mischievously and brushed past me, her aged American Tourister roll-behind suitcase clicking across the tiled foyer.

“Oh, God,” I said, gesturing to the suitcase. “Old Faithful survived the trip. And I was hoping it would fall off the truck.”

“Be quiet,” she whispered. “It might hear you.”

Louise had owned the suitcase since before we were married. Except for some of her grandmother’s jewelry the suitcase was probably Louise’s oldest pre-marriage possession, which I always thought was sort of sad. And I gave her no end of grief over the broken zipper, frayed seams and travel stickers that seemed to hold the antique together.

“I’m hungry,” Louise called from the bedroom. “Wanna order in for pizza?”

“I don’t know,” I said.

“Why not?”

First night in a new house, no television hooked up yet and only the hollow trill of a classic rock FM station wafting from a portable radio. The Rolling Stones and Cream echoed off the bare walls of our new home as we unpacked, talked about walking the few blocks to the Gulf in the morning, and ate ordered-in pizza.

* * *

Ten months later and I’m sitting in a little hospital cafeteria, swirling the last half sip of cold coffee in one of those paper cups—the kind with two useless cardboard wings that are supposed to fold out and make a handle. Like you could even hold a cup of coffee with the damn things.

The doc comes in and right away I can tell something’s wrong. He doesn’t have to say anything. His face is tight as a drum.

You know how people say they have a car wreck and everything slows down? That they can remember every single thing that happened in perfect detail? There were sixteen coffee grounds in the bottom of that worthless paper cup. Sixteen.

“I’m sorry,” he is saying.

I go numb. The soda machine whirs on beside me and I think the compressor must be going out because it’s making a popping sound. Or maybe it’s a belt. Jesus, do the things even have belts anymore? Why is it still running, anyway, when this stranger is sitting here taking my world away?

Bits and pieces of what he’s saying—this highly educated man in the crisp white lab coat and the expensive wingtips—come at me, but the pieces do not fit. They are the sound of car horns in the distance: important to someone, somewhere. But noise to me.

“Stage four…very advanced...”

Car horns.

I see the coffee cup flying, finally using its wings for something worthwhile, and there goes my little splash of cold coffee and my sixteen cold coffee grounds. Godspeed. I see my hands on the small round table and watch it coming up, up and over. Little Heinz mustard packets go flying, somersaulting over the cheap silver napkin box. There’s a distant, muffled crash that blends with the car horns still blaring in my head. The doctor is backing away, his hands out in front of him. Pleading.

Me, too.

* * *

We’re sitting in the water garden we built in the back yard. It isn’t much, really, but we’re proud of it. We worked on it all through that first fall, first putting in the little pond then planting just the right things all around it. She’s gotten so weak that I have to help her walk along the stepping stone path to the Adirondack chair where she sits and dozes for hours, listening to the water tumble over the rocks in the fountain or gazing at the Japanese maple. It’s early evening and the sky is still pink from sunset.

How many left?

She grows quiet and I think she’s dozed off again. I put down the magazine I haven’t been reading and look at her. I do that a lot now. She’s worn thin, her body ravaged by the chemo and the cancer, but her beauty is still there if you know where to look. I do.

Her eyes flutter open and she looks at me. I see the clarity and pain and purpose in those eyes and it startles me.

“It’s all right,” she says, and I hear her reassuring me. She is reassuring me.

“I can’t go to another treatment.” She says this flatly, with iron in her voice. “It will kill me.”

I stare at her for a long time and she does not look away.

“I know,” I say, but it isn’t my voice I hear. It’s the voice of a stranger trying to be more than he is, of a man trying to be strong when strong is what the moment calls for. “I know.”

She nods and, satisfied, lets her tired eyes drift closed. I rise quietly and start up the path toward the house to call the cancer center and cancel our appointment.

“Thank you,” she whispers.

Now it’s my turn to nod because it’s all I can do, all I can give. Because what she has asked for is the only thing I have ever wanted to deny her.

* * *

The kitchen table is covered with a jumble of envelopes, insurance statements and medical bills. If there is anyone anywhere who could make sense of this mess, I think I’d like to meet them. I have tried, and damn hard. But it’s useless. I hold a card from someone I don’t know—the only piece of mail I’ve gotten in weeks that hasn’t been related to money and how much I owe. The front of the card shows a flower in a garden, growing toward a ray of sunshine slanting down from behind a big, billowy cloud. With deepest sympathy in your time of loss, it says on the cover. The flower looks like something in our garden but I don’t know the name of it. Louise was the one who knew what they all were. I wish I could ask her.

The phone rings but I don’t move. The answering machine picks up and I hear my own voice, the me from a million years ago. I remember how many tries it took me to make that recording, how worried I was that I get it just right. What was Louise doing when I was fighting with the machine? A load of laundry, probably, or reading one of her books. She was always reading.

“…your account is seriously past due,” the voice admonishes through the speaker, “…you need to contact us immediately to set up a payment plan…”

What was the last book Louise read? My face goes hot when I realize that I don’t know.

* * *

I am sitting on the couch in the living room while the realtor walks through the house, the heels of her shoes clicking on the hardwood and tile. It seems so loud. I have lived here for months with no other living thing to stir the air.

The realtor comes back in the room, eager and young. She wears a smart business suit and carries a black leather portfolio under her arm.

“I’m so glad you called us about your house. It really is beautiful and we look forward to listing it.”

I nod, wondering what the terms are on the contract in her portfolio.

“However, as I’m sure you’re aware, the housing market has gotten a bit soft recently. We don’t anticipate it will last long, just a little self-correction within the market.” She waves a hand like it’s nothing. “But with a property of this caliber you might be looking at three or four months on the market now, whereas last year you could’ve moved this in, say, six weeks.”

I don’t say anything. I see and hear enough news to know they are throwing around terms like ‘housing slump’ and even ‘housing bubble’. It’s a terrible time to put a house on the market and we both know it. But she has to go through her cheerleader routine, and I have to try. I’m desperate.

“Oh, I don’t think we’ll have any trouble getting your house under contract in ninety to a hundred and twenty days.”

I sign the paperwork and finally see her to the door. She says someone will be by in a day or so to put the sign in the yard, and that I’ll be hearing from her soon. As she drives away, waving from her huge SUV, I can see For Sale signs in front of half a dozen other homes on my street.

I close the front door and go to the kitchen, get myself a glass of tea and walk out to the garden. I sit down slowly in Louise’s chair and close my eyes, feeling for her. And there she is, like always. It’s just her body that’s gone.

I open my eyes to find that the fountain and the Japanese maple are blurry. The tree’s leaves are tired and grim, and there’s a little bare patch underneath where the seed I put down hasn’t taken yet. It probably won’t show until spring. There’s a steel box in the ground underneath that bare spot and in the box there’s an urn. She asked to be buried right here.

I keep hearing something and finally realize it’s the ice jingling against the glass in my hand.

* * *

After three months, a half dozen people have looked at the house and there’s been only one offer; not seventy percent of what I’m asking—what I have to get just to pay off the loan. When the six-month sales contract expires I call the realty office and the receptionist makes excuses. She takes my number and promises someone will get back to me. They never do.

* * *

I turn the corner onto my street and see that the house is dark; too dark. As I get closer I see something white on the front door knob, catching the light from a street lamp. The empty feeling in my stomach changes to something more than hunger as I go up the steps. The paper says it’s a service termination notice. The utility company has turned off my electricity. I fumble the key into the lock and go inside with the notice in one hand and a thin plastic Food King bag in the other.

My feet ache from the shift at work and the walk home. I take off my coat and the bright red vest with the logo that matches the one on the grocery bag. The vest goes onto the back of a chair and a Styrofoam deli container goes onto the coffee table. I sit on the couch. The curtains are open and there’s enough light from the street to see. It’s cool, though. When I’m finished eating I put the plate in the trash, take off my shoes and lay down on the couch, pulling the comforter that used to be on our bed over me. I can still smell her on it, feel her in the warm and familiar folds. This is what I have now, the one part of every day I look forward to. I know it won’t last, though; her scent is already fading. And it is the thought of giving up this last, tangible part of her that makes me lie on the couch for hours sometimes.

* * *

A month after the phone and gas are cut off I miss the first house payment. I will never make another one. Four months after that I sit at the kitchen table on a gray, wet day in December and read the foreclosure notice three times through. I think it should scare me, should send me into a panic. But it doesn’t. I fold the notice back into its envelope, prop it on the counter by the back door and go out to sit with Louise.

“It’s time for us to leave,” I tell her. “We can’t stay here.”

Later than night, when the neighbors have let their dogs out for the last time and stopped peeking out their windows to see what I’m up to, I will come and get Louise. I will steal her back.

* * *

It’s cold out here, and the warmth of the Waffle House coffee is gone, replaced by the wind and exhaust from the passing cars. Their windows are rolled up tight—against the crisp winter air, sure—but against me, too. I know this. My hair is longer than I can ever remember and hasn’t been washed in a long time. The clothes I’m wearing are worn and dirty, my beard ragged. That thin pane of glass between me and the drivers may as well be the armor of a tank as they sit in their warm cars and stare at the traffic light, the steel guard rail, the gravel and trash on the shoulder of the road—anything to keep from looking me in the eye.

That’s okay, though. I was them once, and I wouldn’t look either.

“You should walk some to keep warm,” she says.

“Just a little longer,” I say. “I might get a ride.”

Her silence tells me her opinion of my odds for a ride. I shoulder my pack, take the handle of the American Tourister, and set off. The wheels click loudly on the pavement and the old suitcase bounces along, rattling the stainless steel box inside.

“Where are we going?” she asks.

“Corpus Christi,” I say.

Silence for several paces, or a half mile; it’s hard to say. It’s just beginning to snow and I stop walking to look up at the heavy, gray sky. A few of the first flakes land on my skin and melt as the cars and trucks shoot by, the wind of their passing buffeting me until I am unsteady on my feet. I spread my arms for balance and stand still, letting the feeling of those melting snowflakes sink into my flesh. They are her tears, and I feel them every day.

“Why Corpus Christi?” she asks.

“Why not?”

“Thanks,” I say.

“Sure thing,” she says, then flashes a perfunctory smile and moves on.

The grey sky sits heavy and low outside the windows and I’m in no hurry to leave. It’s cold out there and some of the chill has finally left my hands where I grasp the steaming cup. I start swirling it, watching the little vortex of coffee forming in the middle.

* * *

“Why not?” my wife Louise asked one bitterly cold night in Dayton as we pored over listing after listing on Internet realty sites. “I mean, we’ve waited all this time to enjoy life after work. Now it’s here.”

I was a month away from retiring after nearly four decades with the telephone company, and I was struggling with my wife’s proposition. But I had no solid argument against her logic, either. I rarely did. We had no children and only a few friends we could call close, but there really wasn’t anyone we couldn’t bear the thought of leaving. The truth was that we had waited a long time and now we wanted to do something for ourselves again.

Shortly after the retirement ceremony we drove to Florida to check out some of the places we’d seen on the Internet. We stayed for three days, walking through a dozen houses on the first two; the last day we saved for shopping, putt-putt golf and spontaneous stops for cold drinks or ice cream. This “fun day” was supposed to give us time to relax and let our minds process all the houses we had just walked through—time to think about all the pros and cons of each without the pressure of the realtor standing there. We were also treating ourselves and splurging like we hadn’t done for years, and it felt really good. Our plan was to talk about the houses on the drive back to Ohio and decide whether we should make an offer on any of them. But by the time we finished our complimentary hotel breakfast on the morning of our travel day, it was decided. In the end we sunk all our savings into a down payment on a brand new, two bedroom house—the brochure called it a ‘bungalow’—in an upscale Gulf Coast development called The Villa at Harborside. We would enjoy Harborside for five years, maybe ten, and then sell the place at a healthy profit. We had heard about quite a few couples who were doing the same thing and it seemed like a good plan.

* * *

The U-Haul sat in the driveway, nothing left in it but detritus from the move: a random coin or strip of packing tape, a few Styrofoam peanuts and a stack of haphazardly folded furniture pads. A huge star emblazoned on the truck’s side marked Corpus Christi on an outline of the Lone Star State.

“What are you doing?” I asked, closing the front door behind me. Louise was jetting across the room at her usual breakneck pace, a bundle of clothes draped in the crook of one arm.

“Unpacking, love. It’s the part that usually comes after you’ve packed everything and carried it to the new place.”

“Nobody likes a smart ass.”

“You wouldn’t know what to do without me.” Louise winked mischievously and brushed past me, her aged American Tourister roll-behind suitcase clicking across the tiled foyer.

“Oh, God,” I said, gesturing to the suitcase. “Old Faithful survived the trip. And I was hoping it would fall off the truck.”

“Be quiet,” she whispered. “It might hear you.”

Louise had owned the suitcase since before we were married. Except for some of her grandmother’s jewelry the suitcase was probably Louise’s oldest pre-marriage possession, which I always thought was sort of sad. And I gave her no end of grief over the broken zipper, frayed seams and travel stickers that seemed to hold the antique together.

“I’m hungry,” Louise called from the bedroom. “Wanna order in for pizza?”

“I don’t know,” I said.

“Why not?”

First night in a new house, no television hooked up yet and only the hollow trill of a classic rock FM station wafting from a portable radio. The Rolling Stones and Cream echoed off the bare walls of our new home as we unpacked, talked about walking the few blocks to the Gulf in the morning, and ate ordered-in pizza.

* * *

Ten months later and I’m sitting in a little hospital cafeteria, swirling the last half sip of cold coffee in one of those paper cups—the kind with two useless cardboard wings that are supposed to fold out and make a handle. Like you could even hold a cup of coffee with the damn things.

The doc comes in and right away I can tell something’s wrong. He doesn’t have to say anything. His face is tight as a drum.

You know how people say they have a car wreck and everything slows down? That they can remember every single thing that happened in perfect detail? There were sixteen coffee grounds in the bottom of that worthless paper cup. Sixteen.

“I’m sorry,” he is saying.

I go numb. The soda machine whirs on beside me and I think the compressor must be going out because it’s making a popping sound. Or maybe it’s a belt. Jesus, do the things even have belts anymore? Why is it still running, anyway, when this stranger is sitting here taking my world away?

Bits and pieces of what he’s saying—this highly educated man in the crisp white lab coat and the expensive wingtips—come at me, but the pieces do not fit. They are the sound of car horns in the distance: important to someone, somewhere. But noise to me.

“Stage four…very advanced...”

Car horns.

I see the coffee cup flying, finally using its wings for something worthwhile, and there goes my little splash of cold coffee and my sixteen cold coffee grounds. Godspeed. I see my hands on the small round table and watch it coming up, up and over. Little Heinz mustard packets go flying, somersaulting over the cheap silver napkin box. There’s a distant, muffled crash that blends with the car horns still blaring in my head. The doctor is backing away, his hands out in front of him. Pleading.

Me, too.

* * *

We’re sitting in the water garden we built in the back yard. It isn’t much, really, but we’re proud of it. We worked on it all through that first fall, first putting in the little pond then planting just the right things all around it. She’s gotten so weak that I have to help her walk along the stepping stone path to the Adirondack chair where she sits and dozes for hours, listening to the water tumble over the rocks in the fountain or gazing at the Japanese maple. It’s early evening and the sky is still pink from sunset.

How many left?

She grows quiet and I think she’s dozed off again. I put down the magazine I haven’t been reading and look at her. I do that a lot now. She’s worn thin, her body ravaged by the chemo and the cancer, but her beauty is still there if you know where to look. I do.

Her eyes flutter open and she looks at me. I see the clarity and pain and purpose in those eyes and it startles me.

“It’s all right,” she says, and I hear her reassuring me. She is reassuring me.

“I can’t go to another treatment.” She says this flatly, with iron in her voice. “It will kill me.”

I stare at her for a long time and she does not look away.

“I know,” I say, but it isn’t my voice I hear. It’s the voice of a stranger trying to be more than he is, of a man trying to be strong when strong is what the moment calls for. “I know.”

She nods and, satisfied, lets her tired eyes drift closed. I rise quietly and start up the path toward the house to call the cancer center and cancel our appointment.

“Thank you,” she whispers.

Now it’s my turn to nod because it’s all I can do, all I can give. Because what she has asked for is the only thing I have ever wanted to deny her.

* * *

The kitchen table is covered with a jumble of envelopes, insurance statements and medical bills. If there is anyone anywhere who could make sense of this mess, I think I’d like to meet them. I have tried, and damn hard. But it’s useless. I hold a card from someone I don’t know—the only piece of mail I’ve gotten in weeks that hasn’t been related to money and how much I owe. The front of the card shows a flower in a garden, growing toward a ray of sunshine slanting down from behind a big, billowy cloud. With deepest sympathy in your time of loss, it says on the cover. The flower looks like something in our garden but I don’t know the name of it. Louise was the one who knew what they all were. I wish I could ask her.

The phone rings but I don’t move. The answering machine picks up and I hear my own voice, the me from a million years ago. I remember how many tries it took me to make that recording, how worried I was that I get it just right. What was Louise doing when I was fighting with the machine? A load of laundry, probably, or reading one of her books. She was always reading.

“…your account is seriously past due,” the voice admonishes through the speaker, “…you need to contact us immediately to set up a payment plan…”

What was the last book Louise read? My face goes hot when I realize that I don’t know.

* * *

I am sitting on the couch in the living room while the realtor walks through the house, the heels of her shoes clicking on the hardwood and tile. It seems so loud. I have lived here for months with no other living thing to stir the air.

The realtor comes back in the room, eager and young. She wears a smart business suit and carries a black leather portfolio under her arm.

“I’m so glad you called us about your house. It really is beautiful and we look forward to listing it.”

I nod, wondering what the terms are on the contract in her portfolio.

“However, as I’m sure you’re aware, the housing market has gotten a bit soft recently. We don’t anticipate it will last long, just a little self-correction within the market.” She waves a hand like it’s nothing. “But with a property of this caliber you might be looking at three or four months on the market now, whereas last year you could’ve moved this in, say, six weeks.”

I don’t say anything. I see and hear enough news to know they are throwing around terms like ‘housing slump’ and even ‘housing bubble’. It’s a terrible time to put a house on the market and we both know it. But she has to go through her cheerleader routine, and I have to try. I’m desperate.

“Oh, I don’t think we’ll have any trouble getting your house under contract in ninety to a hundred and twenty days.”

I sign the paperwork and finally see her to the door. She says someone will be by in a day or so to put the sign in the yard, and that I’ll be hearing from her soon. As she drives away, waving from her huge SUV, I can see For Sale signs in front of half a dozen other homes on my street.

I close the front door and go to the kitchen, get myself a glass of tea and walk out to the garden. I sit down slowly in Louise’s chair and close my eyes, feeling for her. And there she is, like always. It’s just her body that’s gone.

I open my eyes to find that the fountain and the Japanese maple are blurry. The tree’s leaves are tired and grim, and there’s a little bare patch underneath where the seed I put down hasn’t taken yet. It probably won’t show until spring. There’s a steel box in the ground underneath that bare spot and in the box there’s an urn. She asked to be buried right here.

I keep hearing something and finally realize it’s the ice jingling against the glass in my hand.

* * *

After three months, a half dozen people have looked at the house and there’s been only one offer; not seventy percent of what I’m asking—what I have to get just to pay off the loan. When the six-month sales contract expires I call the realty office and the receptionist makes excuses. She takes my number and promises someone will get back to me. They never do.

* * *

I turn the corner onto my street and see that the house is dark; too dark. As I get closer I see something white on the front door knob, catching the light from a street lamp. The empty feeling in my stomach changes to something more than hunger as I go up the steps. The paper says it’s a service termination notice. The utility company has turned off my electricity. I fumble the key into the lock and go inside with the notice in one hand and a thin plastic Food King bag in the other.

My feet ache from the shift at work and the walk home. I take off my coat and the bright red vest with the logo that matches the one on the grocery bag. The vest goes onto the back of a chair and a Styrofoam deli container goes onto the coffee table. I sit on the couch. The curtains are open and there’s enough light from the street to see. It’s cool, though. When I’m finished eating I put the plate in the trash, take off my shoes and lay down on the couch, pulling the comforter that used to be on our bed over me. I can still smell her on it, feel her in the warm and familiar folds. This is what I have now, the one part of every day I look forward to. I know it won’t last, though; her scent is already fading. And it is the thought of giving up this last, tangible part of her that makes me lie on the couch for hours sometimes.

* * *

A month after the phone and gas are cut off I miss the first house payment. I will never make another one. Four months after that I sit at the kitchen table on a gray, wet day in December and read the foreclosure notice three times through. I think it should scare me, should send me into a panic. But it doesn’t. I fold the notice back into its envelope, prop it on the counter by the back door and go out to sit with Louise.

“It’s time for us to leave,” I tell her. “We can’t stay here.”

Later than night, when the neighbors have let their dogs out for the last time and stopped peeking out their windows to see what I’m up to, I will come and get Louise. I will steal her back.

* * *

It’s cold out here, and the warmth of the Waffle House coffee is gone, replaced by the wind and exhaust from the passing cars. Their windows are rolled up tight—against the crisp winter air, sure—but against me, too. I know this. My hair is longer than I can ever remember and hasn’t been washed in a long time. The clothes I’m wearing are worn and dirty, my beard ragged. That thin pane of glass between me and the drivers may as well be the armor of a tank as they sit in their warm cars and stare at the traffic light, the steel guard rail, the gravel and trash on the shoulder of the road—anything to keep from looking me in the eye.

That’s okay, though. I was them once, and I wouldn’t look either.

“You should walk some to keep warm,” she says.

“Just a little longer,” I say. “I might get a ride.”

Her silence tells me her opinion of my odds for a ride. I shoulder my pack, take the handle of the American Tourister, and set off. The wheels click loudly on the pavement and the old suitcase bounces along, rattling the stainless steel box inside.

“Where are we going?” she asks.

“Corpus Christi,” I say.

Silence for several paces, or a half mile; it’s hard to say. It’s just beginning to snow and I stop walking to look up at the heavy, gray sky. A few of the first flakes land on my skin and melt as the cars and trucks shoot by, the wind of their passing buffeting me until I am unsteady on my feet. I spread my arms for balance and stand still, letting the feeling of those melting snowflakes sink into my flesh. They are her tears, and I feel them every day.

“Why Corpus Christi?” she asks.

“Why not?”