Sweet the Sound

Nancy McKinley

By

the time I drive Big Blue onto the parking lot of Our Lady of Perpetual Help

Church, all the spaces are filled. Colleen sits in the passenger seat and taps

her foot. “See, Mary Kate, I told you Craig’s funeral would be packed.” She crosses

her arms over her chest, scrunching up her dress so that the lower pleats

unfurl like a black tent.

“I had to go slow around those bikers,” I remind her. We got boxed-in by geezers on motorcycles: gray ponytails hanging below do-rags, no helmets, just beer guts, green t-shirts and denim vests. They passed us with their fists raised, oblivious to the double yellow lines, probably thinking I had Big Blue out for a joy ride. It’s warm for November, yet I never expected them on our route along the Susquehanna River. We’re way north of Lancaster, no draw of Amish farm roads or free tours at the nearby Harley-Davidson Factory.

The hearse, parked by the church steps and flanked by men in military dress uniforms, blocks our way. National Guard from Craig’s unit, I suppose. I shift Big Blue to idle, and we open our windows. Big Blue hums a comfort purr. I came here many Sundays with my grandmother, but not since she died and left me the '81 Buick in her will. Aren’t places supposed to look smaller after you’ve been away? The church looms as large as ever, like an airport hanger topped by a steeple, but the façade of bluestone, mined from Slatington Quarry and sought by builders for its appearance and durability, has faded to chalky-ash.

Colleen sighs, “This will be a long service. Why didn't we eat more at lunch?” We have the afternoon off from the mall, where Melanie, Craig’s wife, now a widow, has a part-time job with Colleen at the Hallmark Store. I work at Books-a-Million, and we take our breaks at the food court. Sometimes they swap stories from Vo Tech, even though Colleen graduated a decade before Melanie. Who'd have figured on a funeral, when a year ago, Melanie peered beneath dark bangs and said Craig was being deployed to Afghanistan?

“He gets a big increase in his monthly check,” announced Melanie.

“That’s good,” I said as Colleen kicked my left shin under the table. I should have anticipated her reaction. Colleen gets enraged by many things, and her favorite rant is the Afghan War. She says Pennsylvania sends more National Guard troops than any other state in the U.S. “They signed up before this mess, looking for extra cash while serving close to home. None imagined seeing combat.”

Thankfully she shut up as Melanie assured us of Craig’s safety: “He'll do supply logistics, arranging who hauls garbage where, that stuff.” Melanie shredded her napkin, and bits of paper stuck to her fingertips. “The money will let us take over the farm when his parents retire.”

Colleen nodded, jaws clamped tight. She was aching to foam about downturn economics, but I figured that would come after work and a bottle of Merlot. She can get going like she's on a soapbox: red hair shaking as she pounds her chest, spouting how her blood is spiked by Celtic warriors until I beg her to cut the crap. Then she dips her chin, "What's it take to get you involved and do something?"

Bob Jenkins, the director of Alderwood Funeral Services, walks toward Big Blue. He’s put on weight, and his hair is butter-white. Leaning to my window, he fills the car with Old Spice, the aftershave used by my grandfather: “Hello, girls.”

I pray Colleen doesn’t take him to task for calling us girls. She smiles politely. Bob Jenkins has a calming influence, undoubtedly why he gets voted coroner even though he runs unopposed. “Best to turn around and park on Mill Street,” he says. His tone, flat and tired, makes me wonder if he’s as sad as we feel. How could this happen when Craig’s deployment was almost over?

No one speaks, and I hear the din of motorcycles coming from behind Big Blue. I check the rear view mirror, but can’t see much other than a green pickup angled at the curb, its tailgate down, the bed piled high with wooden poles sticking out the back.

Bob presses both hands against the car to push upright, “You’ll want to avoid the crowd in the lower lot, so take the side alley.”

As Big Blue weaves past trash cans in the alley, Colleen sucks the back of her teeth, her prelude for home-baked history. How after Vo Tech, Craig said goodbye farming and hello Army. Be All You Can Be meant enlistment in Georgia where he cultivated a hatred for chiggers and long days at a computer, learning ins and outs of trash management. Shortly before his tour ended, his parents sold forty acres to pay for barn repairs. The land was annexed to expand Rivendell, a gated development. Craig returned thinking everything he’d known was slipping away. No more, he vowed. But raising pigs and selling swine to kielbasa makers wasn’t enough to get by.

Then a National Guard recruiter phoned, seeking a man with Army experience. He offered Craig a signing bonus, and the money was just what the family needed. Craig trained one weekend a month at Fort Indiantown Gap until Hurricane Katrina hit the South. He rode in a truck all the way to Baton Rouge where in the ruins of Louisiana bayous, he sat at a computer under a tarp, pole in the middle like a circus tent filled with screeching noise and BO. After Katrina, what were the chances he’d also get sent to Afghanistan?

While months passed with Craig gone to the Middle East, deep lines chiseled the skin around Melanie’s eyes. Colleen started Ladies Stitch and Bitch Nights at her place. I drove Melanie in Big Blue. She turned the radio on full blast and sang: “No white flags above my door. I’m in love–” Dido was Number One on the pop charts, and Melanie relaxed, even more when Colleen poured wine and regaled us with her novel-in-making.

“This is just what I needed, ” said Melanie. “I'm so busy, there's no time to read.” For Colleen that was perfect. None of her supposed book ever makes it to the page. She writes it in her head during long shifts at Hallmark. “Lots of novelists start in the card business,” she proclaimed, opening another bottle of wine.

“Writing cards, not selling them,” I said.

Melanie laughed, holding out her glass for a refill. She gushed how she and the kids, Chelsea, six, and Dan, four, were planning Craig’s welcome home Thanksgiving Dinner. Having invited both sets of parents, brothers, sisters, and their kids, for a total of twenty round the table, Melanie was so excited, she stayed up late and googled recipes of sausage stuffing and Snicker-doodle pie, special treats for Craig.

Then word came of a roadside bombing. Craig arrived two weeks ahead of schedule, his remains in a steel casket, flag draped over the top.

Colleen and I stand in the church under the stained glass window of Jesus cradling a fuzzy, white lamb. Sandwiched with other people who came too late to get a seat, we can’t see the altar. The funeral dirge plays slowly, telling me Mrs. Pavinsky, my grandmother’s friend, is at the organ. Halfway through the song, she loses her place and starts over. “When will they hire a new organist?” whispers Colleen.

I look out over mostly gray and white heads, a field of dandelions gone to seed. The music stops as incense rolls over us. I take shallow breaths through a tissue. Then Father Ryan ascends the pulpit. He looks shorter than I remember, and his collar swallows his neck. Raising his arms, he brings long-fingered hands together in prayer. The lucky people in pews shift to cushioned kneelers. I look down at cold tile and wonder what to do. Suffer it up for Jesus as my school nuns used to say?

Father Ryan rasps: “We gather here– ” but a shrill distortion renders him silent.

“Same bad sound system,” says Colleen. The man beside her smiles. He wears a tweed jacket and has dark, familiar eyes. Colleen nudges me with her elbow. Then I make the connection: Hottie Hajduk. He moved to Colorado eons ago, but in high school, he worked weekends for Craig’s dad. Did he come back for the funeral?

Father Ryan clears his throat and waves so people will sit. There’s a rustling as hips return to wooden seats, yet we remain standing. The National Guard, cordoned off in block formation by the right wall, gaze our way with blank expressions. I wish I could find Melanie. Colleen says she’s been taking Valium ever since the news, and I figure that’s good. I stand on tiptoe, hoping to see the front row where I’m sure she sits with the kids, her parents, and Craig’s mom and dad. I stretch taller, sucking in my stomach, and then a sharp pain stabs my bad, jogger's knee, making me stagger as I grab for Colleen, but down I go.

Colleen kneels, fanning me with the hem of her dress. People turn to look, so I close my eyes, knowing that won’t stop them, but at least I'll focus before trying to stand. Then I smell Old Spice. “Shall we help you up? Get you outside?” asks Bob Jenkins.

With hands under my armpits, he and Colleen guide me through the vestibule. A National Guard opens the heavy oak door. I gulp fresh air and sit on the top step.

Bob Jenkins says, “That incense could make anyone faint.”

I nod. There’s no reason to say I didn’t pass out.

Colleen tells him, “You can go back. I’ll stay with her.”

He gestures toward the door, “Call that Guard if you need him.”

“Thank you,” I say.

Colleen hunkers beside me and points to the lower parking lot. From this height, it looks like a big mitten: the drive is the thumb; the sidewalk, open space, and the parking rows make four fingers. That’s when I could swear I hear Sister Aquinas, my ninth grade Earth Science teacher: Behold the hand of God.

“The bikers are here,” says Colleen.

Am I dizzy? I didn’t whack my head, but sure enough, I failed to notice the geezers. They straddle motorcycles, facing the church. Propped against their handlebars are big American flags. Where did they get them? Then I remember that green pickup. Their flags resemble the five foot marching flag I carried in the Memorial Day Parade when I was a Girl Scout. I wore a holster at my waist, fitted with the base to ease the weight, yet my arms ached.

A biker with a wide-brimmed camouflage hat sees us staring. He lifts his right hand, his fingers in the V-sign for peace.

“Veterans,” says Colleen, her voice hushed.

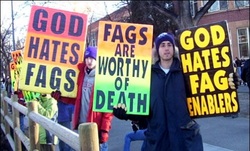

They’re way older than the National Guardsmen. Some have medals pinned to their vests. All wear dog tags with peace sign medallions. Could these guys have served in Viet Nam? I wish I knew what’s going on. That’s when I spy another group in the far parking lot. About twenty men, women, and kids cluster behind a skinny, white-haired guy. He shakes his finger, and a woman in a peculiarly bright blue dress, standing smack in the middle, holds up a sign: God Hates Fags.

Colleen bolts down the stairs. Her dress swooshes out behind her as she stomps onto flat ground and raises her arms. This has to be the fundamentalist group that's been in the news. They picket at funerals of soldiers as retribution for the perceived sins of the nation—crazy stuff about God bringing war to punish our country for homosexuals. Last month, the group protested at a funeral in York, way down I-83. I never imagined them coming here.

I limp behind Colleen until I’m close enough to read more signs. A girl with pigtails and a pink skirt, looking the same age as Craig and Melanie’s daughter, holds a poster board above her head: God’s Will. Beside her, a tall man keeps his sign at chin level: You’re going to Hell.

Colleen yells, "Get out of here!”

The old man cries, “God wants soldiers dead.” His words incite fervor. The group claps like a pep rally gone bad: “God kills soldiers for the sins of fags.”

Colleen shudders: “Unbelievable.”

The group chants with pinched, twisted faces as the bikers rev their engines. Throttles on full, the pitch accelerates over the chanting. The parking lot roars like it’s warm-up at the Daytona 500. This is madness. Where are the cops? What about the National Guard? Then I remember: They’re in church, same as Melanie and her family. The kids. We can’t let them come out and see this.

“Aiee!” screeches Colleen, loud as a Banshee. Her foot paws the ground. Right arm raised like she’s holding a cudgel, she bulks up for the charge. I realize this could be the battle she was born to fight. Her head lulls back and forth, eyes bulge, and she wails. I yell too. Can we tackle them? We’re not far, maybe twenty yards. We ready our two-woman brigade.

Suddenly the biker with the camouflage hat zooms beside us like he’s cavalry, mustering troops. “We’ll handle this. That’s why we came.”

Colleen snorts, eyes wild.

The biker downshifts and uses the heel of his boot to lower the kickstand. He dismounts and moves in front of her. His surprisingly boyish face is a senior biker version of Beatle Paul. With trembling hands, he grabs hold of her wrists, “No violence.”

I arch my spine: “We have to do something.”

His voice is gruff, “Just bring your car. We'll want it for the procession.”

How can I run with a bad knee? I hop-along as Colleen vaults through the alley with me, leg-straight, trying to keep pace. Gasping, we careen onto Mill Street and reach Big Blue. The engine starts right up, a rarity, and I tear-off for the church driveway where the picketers appropriate the black top. I want to topple them like bowling pins, but I motor over sidewalk and lawn, rivaling any SUV as we approach the phalanx of bikers. They don't make room for us, intent on watching the congregation stream from the church, so Big Blue hovers on the grass like a land yacht.

The mourners look toward the parking lot. They cluster on the stairs as if on risers for a photo shoot, but no one smiles.

The old man yells, and his group chants, but they get drowned out as motorcycles rev over their words. Then the people on the stairs part in the middle like Moses at the Red Sea. The pallbearers, all National Guard, stride into the opening with the casket held on their shoulders. They move down the steps to the hearse. As they slide it through the rear door, I sense movement in my peripheral vision. The tall man charges from the lower lot. He's like a running back making an unexpected dash for the end zone.

As he gains yardage on the church, my stomach tightens. Why don't the bikers stop him? I swallow, realizing there's no time to wait. I shift Big Blue into drive and gun-it. We aim straight for him, getting so close, I see his nostrils quiver. That's when Colleen digs her nails into my shoulder. I feather the brake and the guy stops.

Biker Paul pulls up by my window, “Whoa now.”

Colleen whispers, "What the hell?"

I'm panting too hard to speak, and then I see Melanie on the top step. Wearing a black hat with a veil over her face, she puts her hand to her brow and looks in our direction. The bikers swing their flags, creating a breeze that catches the Stars & Stripes and forms a curtain against the hateful presence below. What So Proudly We Hail has never seemed so grand. Then the veterans sing. They have gravel voices, but they chorus, and a few tenors project loudly: Amazing Grace…How sweet the sound…

Colleen sighs. I know she thinks the song is schmaltzy, a term rarely used except by her, yet she joins in, same as the people on the steps. They pivot, turning their backs to the man and his group. No one from the church looks his way.

The National Guard march-in-place. The singing intensifies and reverberates off the bluestone façade of the church. People press shoulder to shoulder, creating a human barrier for Melanie and her children. Heads bowed, they walk down the steps and get in the limousine that will follow the hearse to the cemetery.

The bikers brace flagpoles against their left shoulders and motor ahead. Engines thunder as they ride in formation alongside the vehicles. The funeral procession views waving flags and not those people with horrid signs.

Big Blue joins the line of cars, and I blink away tears. Colleen gently raps her fingers against the dashboard. The small St. Christopher statue my grandmother had glued-on wobbles a bit, but stands strong.

Colleen takes a deep breath. Her voice quivers as she sings: And Grace will lead us home…

I stare through the windshield. It provides a kind of picture frame: late afternoon sun lowered to half-mast, the tree branches like dead limbs, leafless and forlorn.

“I had to go slow around those bikers,” I remind her. We got boxed-in by geezers on motorcycles: gray ponytails hanging below do-rags, no helmets, just beer guts, green t-shirts and denim vests. They passed us with their fists raised, oblivious to the double yellow lines, probably thinking I had Big Blue out for a joy ride. It’s warm for November, yet I never expected them on our route along the Susquehanna River. We’re way north of Lancaster, no draw of Amish farm roads or free tours at the nearby Harley-Davidson Factory.

The hearse, parked by the church steps and flanked by men in military dress uniforms, blocks our way. National Guard from Craig’s unit, I suppose. I shift Big Blue to idle, and we open our windows. Big Blue hums a comfort purr. I came here many Sundays with my grandmother, but not since she died and left me the '81 Buick in her will. Aren’t places supposed to look smaller after you’ve been away? The church looms as large as ever, like an airport hanger topped by a steeple, but the façade of bluestone, mined from Slatington Quarry and sought by builders for its appearance and durability, has faded to chalky-ash.

Colleen sighs, “This will be a long service. Why didn't we eat more at lunch?” We have the afternoon off from the mall, where Melanie, Craig’s wife, now a widow, has a part-time job with Colleen at the Hallmark Store. I work at Books-a-Million, and we take our breaks at the food court. Sometimes they swap stories from Vo Tech, even though Colleen graduated a decade before Melanie. Who'd have figured on a funeral, when a year ago, Melanie peered beneath dark bangs and said Craig was being deployed to Afghanistan?

“He gets a big increase in his monthly check,” announced Melanie.

“That’s good,” I said as Colleen kicked my left shin under the table. I should have anticipated her reaction. Colleen gets enraged by many things, and her favorite rant is the Afghan War. She says Pennsylvania sends more National Guard troops than any other state in the U.S. “They signed up before this mess, looking for extra cash while serving close to home. None imagined seeing combat.”

Thankfully she shut up as Melanie assured us of Craig’s safety: “He'll do supply logistics, arranging who hauls garbage where, that stuff.” Melanie shredded her napkin, and bits of paper stuck to her fingertips. “The money will let us take over the farm when his parents retire.”

Colleen nodded, jaws clamped tight. She was aching to foam about downturn economics, but I figured that would come after work and a bottle of Merlot. She can get going like she's on a soapbox: red hair shaking as she pounds her chest, spouting how her blood is spiked by Celtic warriors until I beg her to cut the crap. Then she dips her chin, "What's it take to get you involved and do something?"

Bob Jenkins, the director of Alderwood Funeral Services, walks toward Big Blue. He’s put on weight, and his hair is butter-white. Leaning to my window, he fills the car with Old Spice, the aftershave used by my grandfather: “Hello, girls.”

I pray Colleen doesn’t take him to task for calling us girls. She smiles politely. Bob Jenkins has a calming influence, undoubtedly why he gets voted coroner even though he runs unopposed. “Best to turn around and park on Mill Street,” he says. His tone, flat and tired, makes me wonder if he’s as sad as we feel. How could this happen when Craig’s deployment was almost over?

No one speaks, and I hear the din of motorcycles coming from behind Big Blue. I check the rear view mirror, but can’t see much other than a green pickup angled at the curb, its tailgate down, the bed piled high with wooden poles sticking out the back.

Bob presses both hands against the car to push upright, “You’ll want to avoid the crowd in the lower lot, so take the side alley.”

As Big Blue weaves past trash cans in the alley, Colleen sucks the back of her teeth, her prelude for home-baked history. How after Vo Tech, Craig said goodbye farming and hello Army. Be All You Can Be meant enlistment in Georgia where he cultivated a hatred for chiggers and long days at a computer, learning ins and outs of trash management. Shortly before his tour ended, his parents sold forty acres to pay for barn repairs. The land was annexed to expand Rivendell, a gated development. Craig returned thinking everything he’d known was slipping away. No more, he vowed. But raising pigs and selling swine to kielbasa makers wasn’t enough to get by.

Then a National Guard recruiter phoned, seeking a man with Army experience. He offered Craig a signing bonus, and the money was just what the family needed. Craig trained one weekend a month at Fort Indiantown Gap until Hurricane Katrina hit the South. He rode in a truck all the way to Baton Rouge where in the ruins of Louisiana bayous, he sat at a computer under a tarp, pole in the middle like a circus tent filled with screeching noise and BO. After Katrina, what were the chances he’d also get sent to Afghanistan?

While months passed with Craig gone to the Middle East, deep lines chiseled the skin around Melanie’s eyes. Colleen started Ladies Stitch and Bitch Nights at her place. I drove Melanie in Big Blue. She turned the radio on full blast and sang: “No white flags above my door. I’m in love–” Dido was Number One on the pop charts, and Melanie relaxed, even more when Colleen poured wine and regaled us with her novel-in-making.

“This is just what I needed, ” said Melanie. “I'm so busy, there's no time to read.” For Colleen that was perfect. None of her supposed book ever makes it to the page. She writes it in her head during long shifts at Hallmark. “Lots of novelists start in the card business,” she proclaimed, opening another bottle of wine.

“Writing cards, not selling them,” I said.

Melanie laughed, holding out her glass for a refill. She gushed how she and the kids, Chelsea, six, and Dan, four, were planning Craig’s welcome home Thanksgiving Dinner. Having invited both sets of parents, brothers, sisters, and their kids, for a total of twenty round the table, Melanie was so excited, she stayed up late and googled recipes of sausage stuffing and Snicker-doodle pie, special treats for Craig.

Then word came of a roadside bombing. Craig arrived two weeks ahead of schedule, his remains in a steel casket, flag draped over the top.

Colleen and I stand in the church under the stained glass window of Jesus cradling a fuzzy, white lamb. Sandwiched with other people who came too late to get a seat, we can’t see the altar. The funeral dirge plays slowly, telling me Mrs. Pavinsky, my grandmother’s friend, is at the organ. Halfway through the song, she loses her place and starts over. “When will they hire a new organist?” whispers Colleen.

I look out over mostly gray and white heads, a field of dandelions gone to seed. The music stops as incense rolls over us. I take shallow breaths through a tissue. Then Father Ryan ascends the pulpit. He looks shorter than I remember, and his collar swallows his neck. Raising his arms, he brings long-fingered hands together in prayer. The lucky people in pews shift to cushioned kneelers. I look down at cold tile and wonder what to do. Suffer it up for Jesus as my school nuns used to say?

Father Ryan rasps: “We gather here– ” but a shrill distortion renders him silent.

“Same bad sound system,” says Colleen. The man beside her smiles. He wears a tweed jacket and has dark, familiar eyes. Colleen nudges me with her elbow. Then I make the connection: Hottie Hajduk. He moved to Colorado eons ago, but in high school, he worked weekends for Craig’s dad. Did he come back for the funeral?

Father Ryan clears his throat and waves so people will sit. There’s a rustling as hips return to wooden seats, yet we remain standing. The National Guard, cordoned off in block formation by the right wall, gaze our way with blank expressions. I wish I could find Melanie. Colleen says she’s been taking Valium ever since the news, and I figure that’s good. I stand on tiptoe, hoping to see the front row where I’m sure she sits with the kids, her parents, and Craig’s mom and dad. I stretch taller, sucking in my stomach, and then a sharp pain stabs my bad, jogger's knee, making me stagger as I grab for Colleen, but down I go.

Colleen kneels, fanning me with the hem of her dress. People turn to look, so I close my eyes, knowing that won’t stop them, but at least I'll focus before trying to stand. Then I smell Old Spice. “Shall we help you up? Get you outside?” asks Bob Jenkins.

With hands under my armpits, he and Colleen guide me through the vestibule. A National Guard opens the heavy oak door. I gulp fresh air and sit on the top step.

Bob Jenkins says, “That incense could make anyone faint.”

I nod. There’s no reason to say I didn’t pass out.

Colleen tells him, “You can go back. I’ll stay with her.”

He gestures toward the door, “Call that Guard if you need him.”

“Thank you,” I say.

Colleen hunkers beside me and points to the lower parking lot. From this height, it looks like a big mitten: the drive is the thumb; the sidewalk, open space, and the parking rows make four fingers. That’s when I could swear I hear Sister Aquinas, my ninth grade Earth Science teacher: Behold the hand of God.

“The bikers are here,” says Colleen.

Am I dizzy? I didn’t whack my head, but sure enough, I failed to notice the geezers. They straddle motorcycles, facing the church. Propped against their handlebars are big American flags. Where did they get them? Then I remember that green pickup. Their flags resemble the five foot marching flag I carried in the Memorial Day Parade when I was a Girl Scout. I wore a holster at my waist, fitted with the base to ease the weight, yet my arms ached.

A biker with a wide-brimmed camouflage hat sees us staring. He lifts his right hand, his fingers in the V-sign for peace.

“Veterans,” says Colleen, her voice hushed.

They’re way older than the National Guardsmen. Some have medals pinned to their vests. All wear dog tags with peace sign medallions. Could these guys have served in Viet Nam? I wish I knew what’s going on. That’s when I spy another group in the far parking lot. About twenty men, women, and kids cluster behind a skinny, white-haired guy. He shakes his finger, and a woman in a peculiarly bright blue dress, standing smack in the middle, holds up a sign: God Hates Fags.

Colleen bolts down the stairs. Her dress swooshes out behind her as she stomps onto flat ground and raises her arms. This has to be the fundamentalist group that's been in the news. They picket at funerals of soldiers as retribution for the perceived sins of the nation—crazy stuff about God bringing war to punish our country for homosexuals. Last month, the group protested at a funeral in York, way down I-83. I never imagined them coming here.

I limp behind Colleen until I’m close enough to read more signs. A girl with pigtails and a pink skirt, looking the same age as Craig and Melanie’s daughter, holds a poster board above her head: God’s Will. Beside her, a tall man keeps his sign at chin level: You’re going to Hell.

Colleen yells, "Get out of here!”

The old man cries, “God wants soldiers dead.” His words incite fervor. The group claps like a pep rally gone bad: “God kills soldiers for the sins of fags.”

Colleen shudders: “Unbelievable.”

The group chants with pinched, twisted faces as the bikers rev their engines. Throttles on full, the pitch accelerates over the chanting. The parking lot roars like it’s warm-up at the Daytona 500. This is madness. Where are the cops? What about the National Guard? Then I remember: They’re in church, same as Melanie and her family. The kids. We can’t let them come out and see this.

“Aiee!” screeches Colleen, loud as a Banshee. Her foot paws the ground. Right arm raised like she’s holding a cudgel, she bulks up for the charge. I realize this could be the battle she was born to fight. Her head lulls back and forth, eyes bulge, and she wails. I yell too. Can we tackle them? We’re not far, maybe twenty yards. We ready our two-woman brigade.

Suddenly the biker with the camouflage hat zooms beside us like he’s cavalry, mustering troops. “We’ll handle this. That’s why we came.”

Colleen snorts, eyes wild.

The biker downshifts and uses the heel of his boot to lower the kickstand. He dismounts and moves in front of her. His surprisingly boyish face is a senior biker version of Beatle Paul. With trembling hands, he grabs hold of her wrists, “No violence.”

I arch my spine: “We have to do something.”

His voice is gruff, “Just bring your car. We'll want it for the procession.”

How can I run with a bad knee? I hop-along as Colleen vaults through the alley with me, leg-straight, trying to keep pace. Gasping, we careen onto Mill Street and reach Big Blue. The engine starts right up, a rarity, and I tear-off for the church driveway where the picketers appropriate the black top. I want to topple them like bowling pins, but I motor over sidewalk and lawn, rivaling any SUV as we approach the phalanx of bikers. They don't make room for us, intent on watching the congregation stream from the church, so Big Blue hovers on the grass like a land yacht.

The mourners look toward the parking lot. They cluster on the stairs as if on risers for a photo shoot, but no one smiles.

The old man yells, and his group chants, but they get drowned out as motorcycles rev over their words. Then the people on the stairs part in the middle like Moses at the Red Sea. The pallbearers, all National Guard, stride into the opening with the casket held on their shoulders. They move down the steps to the hearse. As they slide it through the rear door, I sense movement in my peripheral vision. The tall man charges from the lower lot. He's like a running back making an unexpected dash for the end zone.

As he gains yardage on the church, my stomach tightens. Why don't the bikers stop him? I swallow, realizing there's no time to wait. I shift Big Blue into drive and gun-it. We aim straight for him, getting so close, I see his nostrils quiver. That's when Colleen digs her nails into my shoulder. I feather the brake and the guy stops.

Biker Paul pulls up by my window, “Whoa now.”

Colleen whispers, "What the hell?"

I'm panting too hard to speak, and then I see Melanie on the top step. Wearing a black hat with a veil over her face, she puts her hand to her brow and looks in our direction. The bikers swing their flags, creating a breeze that catches the Stars & Stripes and forms a curtain against the hateful presence below. What So Proudly We Hail has never seemed so grand. Then the veterans sing. They have gravel voices, but they chorus, and a few tenors project loudly: Amazing Grace…How sweet the sound…

Colleen sighs. I know she thinks the song is schmaltzy, a term rarely used except by her, yet she joins in, same as the people on the steps. They pivot, turning their backs to the man and his group. No one from the church looks his way.

The National Guard march-in-place. The singing intensifies and reverberates off the bluestone façade of the church. People press shoulder to shoulder, creating a human barrier for Melanie and her children. Heads bowed, they walk down the steps and get in the limousine that will follow the hearse to the cemetery.

The bikers brace flagpoles against their left shoulders and motor ahead. Engines thunder as they ride in formation alongside the vehicles. The funeral procession views waving flags and not those people with horrid signs.

Big Blue joins the line of cars, and I blink away tears. Colleen gently raps her fingers against the dashboard. The small St. Christopher statue my grandmother had glued-on wobbles a bit, but stands strong.

Colleen takes a deep breath. Her voice quivers as she sings: And Grace will lead us home…

I stare through the windshield. It provides a kind of picture frame: late afternoon sun lowered to half-mast, the tree branches like dead limbs, leafless and forlorn.