Shelter in Place

Phebe Jewell

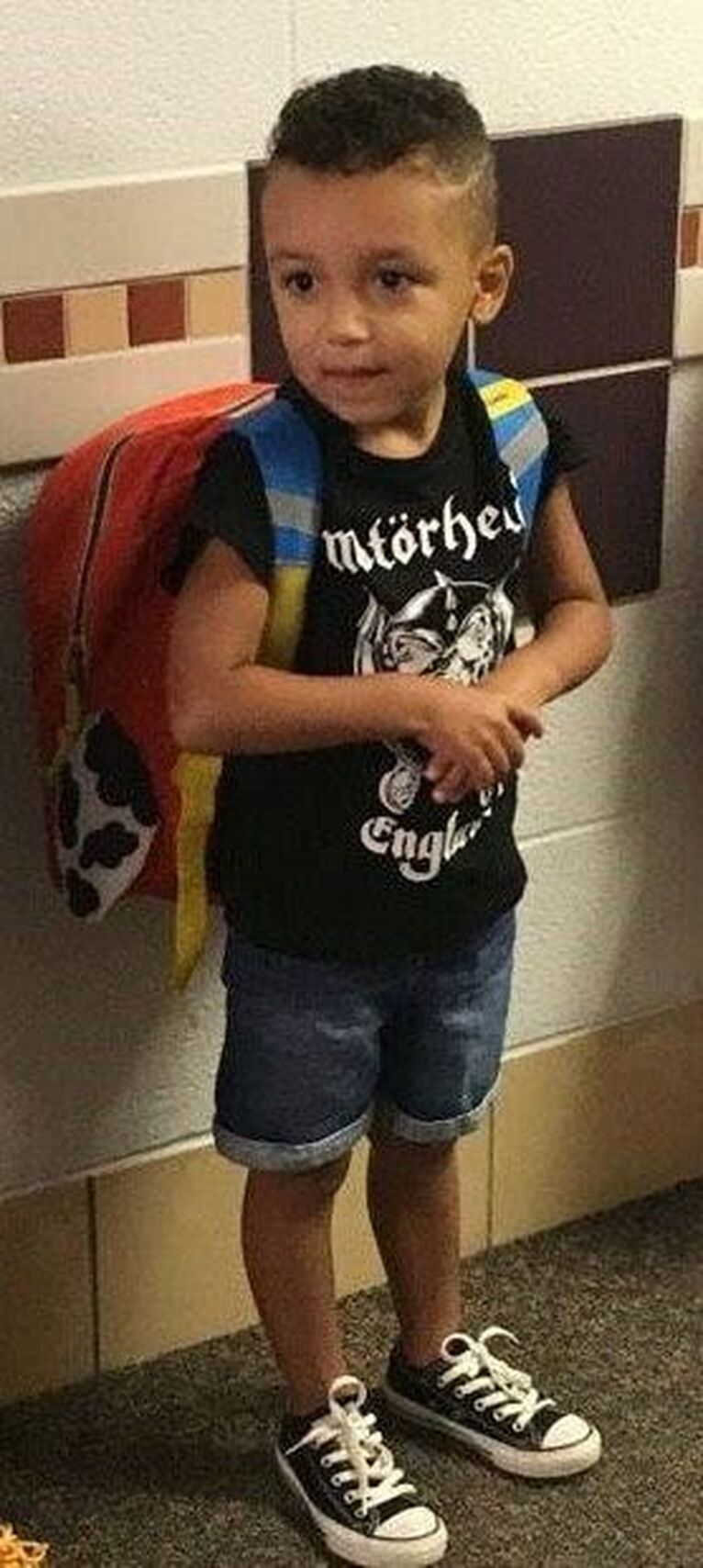

First day of kindergarten. Circle time is hard. Bursting with new words, he forgets to raise his hand. His teacher smells like fried food left on the counter all day. She yells at him for talking too loud, for coloring the sky orange. By December his desk faces a wall.

First grade. The teacher says boys like him will end up in juvie. What is that? Where is it? How would he get home?

Second grade. First suspension. He kicks the table legs while his parents listen to the teacher talk about supports. His stomach hurts every day. At recess he swings, butt back, legs straight out front, pumping, waiting for lift off.

Third grade. Second suspension. His parents move him to a new school. This teacher is like a mother. She hugs him, calls him “Sugar,” and rewards him with jellybeans.

Fourth grade. He stares at a page and has no place to rest his eyes. The other kids are already at the end of the story. Maybe he can read better in the hallway where it’s not too noisy. He sits cross-legged, listening to the kids laugh and talk on the other side of the wall. The principal walks by and tells him to go back to the classroom. She tells him to work hard so he can get ahead. Ahead of what? He goes to the nurse. She has a soft voice and a chair by the window. His parents ask what’s wrong. He can’t answer.

Fifth grade. Listening to him play the dozens with his friends, his teacher scolds them. Speak properly, she says. More white. He stops raising his hand in class.

Sixth grade. Halfway through the school year, his teacher takes a job at a better school in the north end.

Seventh grade. Big for his age, he gets followed in stores. When he asks his teacher why she only sends the black and brown boys out of the classroom, she tells him she can’t be racist because her brother-in-law is black.

Eighth grade. Three-week suspension. The first day back he waits with his friends for the school bus. A patrol car circles the block, windows rolled down, officers staring at the boys, memorizing their faces.

Freshman year of high school. He rides his bike to school, but someone keeps deflating his tires. Walking to the bus, he passes a man with bad dreads who yells at him. Cars thump by, slowing, then speeding down the block. Last year a kid was shot at the bus stop. He knows the bus schedule by heart so he won’t have to wait more than a minute. Showing his pass, he scans the row of seats without moving his head. Makes sure he’s wearing three colors so no one thinks he’s banging.

He’s always hungry now but can’t find the right food. The oatmeal his mom makes cools while he gets dressed for school. His parents don’t allow junk food in the house, so his friends share bags of chips, candy bars, pop. He shoves them in his backpack for later, pulling them out after school. Dinner is a fork pushing food on a plate. Midnight and he’s the only one up in the silent house, watching gamers and racecar drivers on Youtube, washing down a jumbo bag of Oreos with a 40-ounce jug of Gatorade. Someday he’ll have his own show, filmed entirely in his room. He falls asleep with his glasses on.

Sophomore year. He keeps his hands to himself. His teachers tell his parents he’s a good kid. They don’t know why his grades are so bad. He doesn’t cause trouble, he has a quick mind when he wants. Wrangling disruptive students, they don’t notice him disappear.

Junior year. This year’s gang season lasts months. For weeks the helicopters circle the school, the neighborhood, searching. He comes home early, goes straight to his room. Headphones on, he eats pocket pies in bed, mesmerized by scenes of Navy Seals achieving the impossible.

Senior year. He’s so big now he scares himself. Skipping last period, he sneaks home to his room. He tears open a bag of chips and chews his fear, swallowing the teachers and the gangs and the cops. The door is closed, the light off. He’s on his bed, back to the wall. No one can find him behind a door too narrow to squeeze through.

Phebe Jewell

First day of kindergarten. Circle time is hard. Bursting with new words, he forgets to raise his hand. His teacher smells like fried food left on the counter all day. She yells at him for talking too loud, for coloring the sky orange. By December his desk faces a wall.

First grade. The teacher says boys like him will end up in juvie. What is that? Where is it? How would he get home?

Second grade. First suspension. He kicks the table legs while his parents listen to the teacher talk about supports. His stomach hurts every day. At recess he swings, butt back, legs straight out front, pumping, waiting for lift off.

Third grade. Second suspension. His parents move him to a new school. This teacher is like a mother. She hugs him, calls him “Sugar,” and rewards him with jellybeans.

Fourth grade. He stares at a page and has no place to rest his eyes. The other kids are already at the end of the story. Maybe he can read better in the hallway where it’s not too noisy. He sits cross-legged, listening to the kids laugh and talk on the other side of the wall. The principal walks by and tells him to go back to the classroom. She tells him to work hard so he can get ahead. Ahead of what? He goes to the nurse. She has a soft voice and a chair by the window. His parents ask what’s wrong. He can’t answer.

Fifth grade. Listening to him play the dozens with his friends, his teacher scolds them. Speak properly, she says. More white. He stops raising his hand in class.

Sixth grade. Halfway through the school year, his teacher takes a job at a better school in the north end.

Seventh grade. Big for his age, he gets followed in stores. When he asks his teacher why she only sends the black and brown boys out of the classroom, she tells him she can’t be racist because her brother-in-law is black.

Eighth grade. Three-week suspension. The first day back he waits with his friends for the school bus. A patrol car circles the block, windows rolled down, officers staring at the boys, memorizing their faces.

Freshman year of high school. He rides his bike to school, but someone keeps deflating his tires. Walking to the bus, he passes a man with bad dreads who yells at him. Cars thump by, slowing, then speeding down the block. Last year a kid was shot at the bus stop. He knows the bus schedule by heart so he won’t have to wait more than a minute. Showing his pass, he scans the row of seats without moving his head. Makes sure he’s wearing three colors so no one thinks he’s banging.

He’s always hungry now but can’t find the right food. The oatmeal his mom makes cools while he gets dressed for school. His parents don’t allow junk food in the house, so his friends share bags of chips, candy bars, pop. He shoves them in his backpack for later, pulling them out after school. Dinner is a fork pushing food on a plate. Midnight and he’s the only one up in the silent house, watching gamers and racecar drivers on Youtube, washing down a jumbo bag of Oreos with a 40-ounce jug of Gatorade. Someday he’ll have his own show, filmed entirely in his room. He falls asleep with his glasses on.

Sophomore year. He keeps his hands to himself. His teachers tell his parents he’s a good kid. They don’t know why his grades are so bad. He doesn’t cause trouble, he has a quick mind when he wants. Wrangling disruptive students, they don’t notice him disappear.

Junior year. This year’s gang season lasts months. For weeks the helicopters circle the school, the neighborhood, searching. He comes home early, goes straight to his room. Headphones on, he eats pocket pies in bed, mesmerized by scenes of Navy Seals achieving the impossible.

Senior year. He’s so big now he scares himself. Skipping last period, he sneaks home to his room. He tears open a bag of chips and chews his fear, swallowing the teachers and the gangs and the cops. The door is closed, the light off. He’s on his bed, back to the wall. No one can find him behind a door too narrow to squeeze through.