Liberty Turns

Neil Mathison

I’d

asked to stand the shutdown watch; a nostalgic gesture because I was quitting

the Navy. I liked the orderliness of shutdown: the deliberate securing of

equipment, the careful sequence so that the connections that sustained us at

sea, the webs of neutrons and electrons and steam severed one by one until the

ship ceased to be a thing apart. After the last reactor SCRAMMED, I went back

to my stateroom. I changed into civvies. I carried my sea bag up to the

quarterdeck. I shook hands with a couple of my buddies who’d come to see me

off. The OOD signed my separation orders. I heaved the sea bag over my

shoulder, I faced the flag on the fantail and stood at attention which is what

you did instead of saluting when you wore civvies off the ship, although I

wasn’t in the Navy anymore and I didn’t have to salute anybody; and that was

it. I was out.

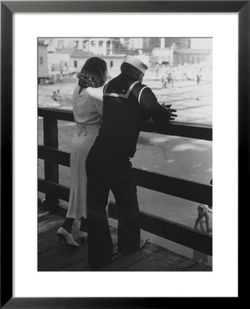

The pier was empty. The wives and kids and girlfriends who’d come to meet the ship were long gone. The Navy band stood around waiting for the bus. Tubas and golden Sousaphones gleamed in the California sun. The ship loomed over the pier and the Bay Bridge towers rose above the fog like a drowning man’s arms. At the end of the pier, I spotted Sylvie. I broke into a jog, my sea bag thumping against my back.

We’d kicked Saddam’s butt and we’d come home but it wasn’t the homecoming I’d planned. My fiancée, Sharon, had run off with a born-again naval aviator. I’d had a fantasy of sweeping Sharon out of her fly-boy’s arms, except in my heart, I knew it wasn’t going to happen. “I found Jesus,” Sharon wrote, “and the man I’ll spend my life with. Take care of yourself. God loves you.”

Until Sharon’s letter, I’d agreed with Einstein. God didn’t play dice. When other people experienced busted engagements, it was, I figured, because they hadn’t paid attention to the trajectory of their relationships. If you controlled the initial conditions, I believed, you controlled the outcome. E equaled MC2; force was mass times acceleration; the laws of physics had to be obeyed. Don’t get me wrong. I knew chaos was out there, a dark, December chaos of the night, but I believed you could – if you wanted it bad enough – keep the candles burning. I wasn’t going to be like my dad. He’d allowed himself to be sucked into the night.

I dropped my sea bag at Sylvie’s feet and I hugged her. My best friend’s wife was tall and slender and copper-skinned and she had these high planar cheeks and the slightest folds at the corners of each eye – “From my Apache grandmother,” Sylvie always explained – and she was a painter and a pottery artist and she favored bright-colored shawls and dark tights and she was holding a bouquet of flowers. “Bouquets for the returning hero,” she said, handing me the flowers. “The ship was early.”

“Liberty turns,” I answered.

Sylvie nodded. As a Navy wife, she knew what liberty turns meant: the extra speed added by the engineers to get the ship home faster.

“Sorry about Sharon.”

“I’ll get over it.”

“I know.” She squeezed my arm and began steering me to the parking lot.

“You heard from Bunkie?”

“You know Bunkie. Everything’s hunky dory. The Tennessee has the best captain and best crew. It’s the finest ship in WESTPAC.” Sylvie mimicked Bunkie’s enthusiastic drawl. “He’s already married to the damned ship!”

“And you?”

“WESTPAC widow and nearly used to it.” Sylvie stopped next to a classic red Stingray, a ’67.

“New wheels?”

“Borrowed.” Sylvie opened the driver-side door. “Toss your gear in the back. We’ve got a homecoming to celebrate.”

The Vette rumbled down Shoreline Drive. Mowed grass scented the air. Birds sang. Car horns honked. Sirens wailed. Kids shouted. Apartment-house windows flashed in the sunlight. Billboards and neon signs and traffic lights blazed a tumult of colors. I felt fragile, like I was being swept up in a typhoon of stimuli.

“You okay?” Sylvie asked, shooting me a concerned glance.

“Overwhelmed,” I answered.

“Bunkie says coming home from sea is like stepping from black-and-white into a rainbow.”

We crossed the High Street Bridge and swung south up the ramp to I-880.

“Hang on!” Sylvie announced. The Stingray took off in a blaze of acceleration. Sylvie drove like a pilot dodging Iraqi flak. We zigzagged lane to lane passing semi-trucks and buses and the late rush-hour traffic. I braced against the dashboard, my heart racing and my palms sweating, but it was more than just Sylvie’s driving that made my heart race. I had no plan, no job, no girl, no idea where life was taking me. I had failed to set the initial conditions. We barreled down the freeway heading God-knows-where and the sun had set and San Francisco across the bay vanished into a fog-shrouded night.

Before my dad committed suicide, he’d sometimes come to our room after my mom put my brother and me to bed. If he’d been drinking, he’d tell us stories about Nam: about punji stakes and booby-traps; how we dropped so many white phosphorus flares, it was never really night; how boom boom was what Vietnamese called sex; about crotch rot and jungle foot and LZ s and bouncing bettys. I remember the whiskey on his breath and I remember imagining a Vietnam where it was never night and where the people called sex by weird names. Dad always finished with the same story, about him coming home and how, as he waited in the airport for Mom, “long hairs spit on my boots.” I pictured him sitting there in the airport lounge in his starched Army uniform, wearing his Ranger’s beret and his black jump boots and then the “long hairs” spitting on him. The boots stood in the closet downstairs, as bright and black and shiny as they’d been the day he came home from Nam. “Boys,” he’d say, “that’s the thanks we got.” He’d shake his head. Then he’d pull the covers up to our chins, give us each a kiss, and he’d go back down where the lights were turned out and where he had his whiskey bottle and where he could lose himself to the night.

Sylvie and I exited the 880 south of Fremont and headed east. The area was unfamiliar to me – strip malls, fast-food franchises, discount shopping centers, U-Haul rentals, storage lockers, 7-11s – the detritus of American life.

Sylvie shot through an intersection as the light turned red.

“Where are we going?” I managed to ask, gripping the edge of my seat.

“I’m house-sitting,” she explained. “A dentist’s house.”

“Have I met the dentist?”

“You’ll meet him tonight.”

“You’re house sitting for somebody who’s home?”

“He travels a lot. He’s a Navy dentist.”

Gradually we climbed above the grid of malls and street lights and headlights. The air smelled of eucalyptus. We leaned around curves as Sylvie sped up a switchback road. The Stingray’s tires sang on the asphalt.

“What are you going to do,” Sylvie asked, “now that you’re out of the Navy?”

Find a woman like you, I thought. “Don’t know,” I said. “Travel around. Get a motorcycle.” Until that moment, I’d never considered getting a motorcycle.

“Bunkie never wants to go anywhere. He says he’s been everywhere in the Navy except home.”

I tended to agree with Bunkie.

“It’d be good to travel,” Sylvie said, as she braked into a carport.

I recognized Bunkie and Sylvie’s Volvo in the driveway. Cactus and spiny Yucca grew in a rock garden. From somewhere sprinklers were ratcheting. The house was all angles: glass, stone, and steel. Light blazed from picture windows. I hauled my sea bag out of the Stingray and followed Sylvie up the steps to an enormous mahogany door that was carved with intricate, abstract designs – it looked like a nest of snakes. Sylvie unlocked the door.

“We’re home!” she yelled.

“Yo!” a male voice answered.

The room was all white, the walls were white, the carpets were white, the sofas and stuffed chairs were white, the steel beams in the ceiling were white. Wrought-iron stairways spiraled up to the second floor and down to the basement. The wrought iron was white. Here and there were objects of Asian art – a Japanese print of a wave breaking in finger-like tendrils, a black and red kabuki mask, a bronze temple bell. One wall was covered with a painting of a woman with dozens of arms and a fiery, snake-head halo. A sculpture of a male torso in ebony wood stood inside the doorway. I heard the clank of metal striking metal in a steady, metronome beat.

“Let me introduce you to Karl.” Sylvie clanged down the spiral stairs.

The lower floor – I guess it was the basement – was an open room with barbells and dumbbells and mirrors and a Universal Gym. A door opened to a cedar-wood sauna. A man lay under the gym, pressing a chrome bar up and down. Each time the weights dropped, they sounded a bell-like knell.

“Just a sec,” the man said. “I got to finish this set.”

He wore blue Spandex shirt and shorts. His skin was tanned. His head was completely bald although he couldn’t have been older than thirty-five or forty. I watched him extend and collapse his arms. Sylvie and I waited silently for him to finish. He settled the weights gently and slid out from under the bar.

“This is Karl,” Sylvie said.

Karl reached out and wrung my hand. “Heard you were in the Gulf.” He fixed me with cavernous eyes, the eyes of a hawk. “We kicked some butt, didn’t we?”

We, I thought. What’s with “we?”

“You boys get acquainted. I’ll start dinner.” Sylvie kissed Karl’s cheek.

Karl peeled himself from his Spandex, dropping his shorts and shirt to the floor, apparently untroubled that he was standing in front of a stranger naked. He pulled a towel off a rack and wrapped it around his waist. I looked away.

“Care for a sauna?”

“No thanks.”

“I envy you. Being in a real battle. Nietzsche calls war the grand sagacity of every spirit; its curative power lies even in the wounds one receives.”

“No wounds,” I said. “Spent the war babysitting the ship’s reactors.”

“Physics.” Karl glanced up at the ceiling thoughtfully.

I followed his gaze. There were flecks in the plaster that sparkled in the light.

“We must be physicists to be creative since so far the codes and ideals have been constructed in ignorance of physics. Nietzsche said that too. The Kraut knows life.” Karl stepped into the sauna and sat down on a wooden bench with the towel draped across his lap. The sauna door was still open. I could feel the hot, dry air seeping into the room.

“You’re a dentist?” I said.

“That’s right.” From inside the sauna his voice sounded hollow and sepulchral.

“Sylvie says you’re away a lot.”

“Hawaii. Guam. Japan. Diego Garcia. You’d be surprised at who doesn’t practice dental hygiene. Take CINPAC. Commands the entire Pacific Fleet. Doesn’t floss!”

I wasn’t sure what was worse: Nietzsche or CINCPAC’s teeth.

“Let him go Karl,” Sylvie called from upstairs. “He’ll want to wash up.”

“You’ll be bunking on the main floor,” Karl said. “Sylvie’ll show you the way.” He swung the sauna door shut.

I clambered up the metal stairs.

Sylvie stood in front of an industrial-sized stove in a large kitchen. A wok simmered on a gas burner. Shrimp and pea shoots sautéed in the wok and the kitchen was filled with the fragrance of soy and hot sesame oil. The window behind the stove looked out over the canyon. There were a few houses here and there, most steel and concrete like Karl’s. Beyond the houses, the lights of Fremont and San Leandro and Oakland stretched into the night; the bridges, the San Mateo and the San Rafael, spanned the bay like headlight-beaded webs.

“Smells like heaven,” I said.

“There’s a beer in the fridge.” Sylvie stirred the sizzling wok with a wooden spoon.

“A Nietzsche-quoting dentist?”

Sylvie didn’t look up.

“Rich?”

“Family money,” Sylvie said.

“Sylvie,” I began, “what exactly is your situation here?”

“Get showered,” she answered. “Chow in thirty minutes. Towels on the bed.” She patted my cheek. “Don’t be late – the cook doesn’t like tardy victims.”

I hauled my stuff into the guest room.

But where Sylvie had touched my cheek, I felt a kind of cool, electric fizz. I was suddenly horny. How many months had it been? Nine? Ten? With Sharon. I’d remained true to Sharon. I’d wanted the initial conditions for our marriage to be perfect, without a flaw or blemish; I’d invested myself in celibacy (even if the investment hadn’t paid off). What’s more, what was going on with Sylvie and her Ubermensch dentist? What should I do about that?

The dining room was as cavernous as a mausoleum. A vast ebony-wood table stretched between us with Karl on one end and Sylvie on the other and me in the middle. Sylvie had placed candles in the center and turned the lights down and the candles flickered and cast shadows that danced across the walls like one of Karl’s creepy paintings. Across the table from me, against the white wall, was a statue of Kali, the Hindu goddess of destruction: skulls in her arms; legs contorted in a big-stepping dance. With the chilly room and the freaky statue and the spooky light I was losing my appetite. Karl wolfed his food. We drank a bottle of wine and another. Karl asked me questions about the war. I tried to answer but Karl knew more about the war than I did. He’d watched CNN and I’d only watched the ship’s reactors. I could tell Karl was disappointed. He wanted to hear about the “sagacity of war” or “the curative power of wounds.”

“So you quit the Navy,” he finally said. “And your woman left you?”

“Karl!” Sylvie slapped the table with the palm of her hand.

Karl waved her away. “The true man wants two things: danger and play. For that reason he wants woman, as the most dangerous plaything. Nietzsche said that.”

My face began to burn. I felt as if Karl had barged into a private room, where he didn’t belong, a room where I’d locked up my grief.

“Cool it,” Sylvie said.

“For the woman, the man is the means: the end is always the child. He said that too.”

“So much for the female fifty-one percent of humanity,” Sylvie said.

I wondered if Nietzsche was as big a prick as Karl.

Karl’s elbows were on the table and his chin was resting in his hands. Like he was posed as some kind of philosopher-king. He turned to face me, a weary smile on his face. “Your woman got religion. Right? Not much difference between religion and lust…”

“Let me guess,” Sylvie interrupted. “Nietzsche. Get your butt in the kitchen. Start the dishwasher.”

Karl laughed. “That’s my Sylvie! Resolves philosophy in a dishwasher.” He pushed his chair back, stood up, and padded into the kitchen.

For a minute, Sylvie faced me across the table.

I was angrier at her than I was at Karl. I’d told her about Sharon. She’d told Karl.

“I’m sorry,” she said.

“I think I’ll hit the sack.” I stood up.

“Do you want to talk?” she said.

I walked out of the room.

In the bedroom, I lay on the bed, the lights out. The moon had come up and a cold white light shown through the window. I thought of my dad and his war in Vietnam and how his war hadn’t been as tidy as my own. Every time our family moved, he’d carefully pack his souvenirs – the cracked photographs of buddies who’d been long dead, his honorable discharge, the North Vietnamese officer’s pistol he’d found. When we got to a new house, he’d arrange these things in a prominent place, on the fireplace mantle, on a living room bookshelf. Mother hated them. I can’t forget the war, he’d tell us. I’ll never forget it. He came home and he went to college and he got married but he used Vietnam to justify everything that went wrong in his life: his falling-apart marriage, his drinking too much, his many affairs with women. Once he attempted to explain his behavior to me. Son, he said, I’m living on borrowed time. I’m not going to take a chance I’ll miss anything. In the end, he missed everything.

Vietnam betrayed my dad and my dad betrayed my mother and Sharon betrayed me and Sylvie had betrayed my secrets to her dentist and she’d probably betrayed Bunkie as well. Was betrayal how it had to be? I lay in the bed brooding until I fell asleep.

I woke when I heard the bedroom door open. Sylvie stepped in and she closed the door behind her. In the moonlight, I watched her open her robe and I heard the rustle as her robe fell to the floor. Her skin was white– her breasts and belly and legs were white except for the darkness at the tips of her breasts. She leaned over me and she brushed her fingers over my lips. “Hush,” she whispered.

The darkness surrounded us and the night closed over us. We’re doing this, I thought, Sylvie and I are doing this. I thought of Bunkie and of Sharon and even of my dad. Then Sylvie raised herself above me and she arched her back and her head tipped back and I felt the heat where our bodies joined, hot and bright and I didn’t think of anything except Sylvie. It was too late. It was too late for Dad, too late for Sharon and Bunkie, too late to escape the night.

Afterwards, Sylvie cradled her head in the crook of my arm.

“How long have you been seeing Karl?” I whispered.

“I don’t see him. I housesit for him.”

“You don’t sleep with him?”

“I don’t think he sleeps with women.” For a moment she was silent. “I’m so lonely,” she whispered. “I just want someone to talk to.”

“Is he gay?”

I could feel Sylvie shrug.

“Is this about pity? Or about us? Or something else?” I whispered this as if I was whispering only to myself and I wasn’t sure she heard me.

Then she answered. “Isn’t it strange? We’re still young and we’re still sexy and if we love somebody in the Navy or if we’re in the Navy we go months without sex.” She placed her hand on my belly. She slipped her leg between mine. “I guess talk isn’t enough.”

I thought of Bunkie in the Gulf. It would be morning there, and the sun would have risen and the hot light would blaze off the sea. I thought of how Dad had finally killed himself, of how he’d blown his brains out in the living room of our house with his North Vietnamese officer’s pistol. I thought of his black-and-white snapshots of his dead buddies. I thought of his blood on the living-room rug. Was there an arc to these things? Was there a difference between day and night? Was betrayal inevitable? I heard the steady inhale and exhale of Sylvie’s breath. I lifted Sylvie’s leg and swung out of bed, taking care not to wake her. I put on my running shorts and shoes, and slipped out the bedroom door. I walked across the empty expanse of Karl’s living room. I opened the front door. I could see the entire peninsula below the house and the fog had lifted and the lights shone all the way to San Francisco like jewels on a black cloak. The air was dry but I could smell things growing: the grasses, the eucalyptus. A full moon cast a light purer than daylight.

I began to jog, following the road uphill, beyond Karl’s house. The grass at the crest of the hill had been blackened by wildfire. I could see the line where the fire had stopped. Except for the sound of my feet, it was silent -- no birdsong, no crickets. I fell into the rhythm of running, listening to the sound of my breathing, to the beat of my heart, but I was straining to hear something else, but what I heard was only silence.

The pier was empty. The wives and kids and girlfriends who’d come to meet the ship were long gone. The Navy band stood around waiting for the bus. Tubas and golden Sousaphones gleamed in the California sun. The ship loomed over the pier and the Bay Bridge towers rose above the fog like a drowning man’s arms. At the end of the pier, I spotted Sylvie. I broke into a jog, my sea bag thumping against my back.

We’d kicked Saddam’s butt and we’d come home but it wasn’t the homecoming I’d planned. My fiancée, Sharon, had run off with a born-again naval aviator. I’d had a fantasy of sweeping Sharon out of her fly-boy’s arms, except in my heart, I knew it wasn’t going to happen. “I found Jesus,” Sharon wrote, “and the man I’ll spend my life with. Take care of yourself. God loves you.”

Until Sharon’s letter, I’d agreed with Einstein. God didn’t play dice. When other people experienced busted engagements, it was, I figured, because they hadn’t paid attention to the trajectory of their relationships. If you controlled the initial conditions, I believed, you controlled the outcome. E equaled MC2; force was mass times acceleration; the laws of physics had to be obeyed. Don’t get me wrong. I knew chaos was out there, a dark, December chaos of the night, but I believed you could – if you wanted it bad enough – keep the candles burning. I wasn’t going to be like my dad. He’d allowed himself to be sucked into the night.

I dropped my sea bag at Sylvie’s feet and I hugged her. My best friend’s wife was tall and slender and copper-skinned and she had these high planar cheeks and the slightest folds at the corners of each eye – “From my Apache grandmother,” Sylvie always explained – and she was a painter and a pottery artist and she favored bright-colored shawls and dark tights and she was holding a bouquet of flowers. “Bouquets for the returning hero,” she said, handing me the flowers. “The ship was early.”

“Liberty turns,” I answered.

Sylvie nodded. As a Navy wife, she knew what liberty turns meant: the extra speed added by the engineers to get the ship home faster.

“Sorry about Sharon.”

“I’ll get over it.”

“I know.” She squeezed my arm and began steering me to the parking lot.

“You heard from Bunkie?”

“You know Bunkie. Everything’s hunky dory. The Tennessee has the best captain and best crew. It’s the finest ship in WESTPAC.” Sylvie mimicked Bunkie’s enthusiastic drawl. “He’s already married to the damned ship!”

“And you?”

“WESTPAC widow and nearly used to it.” Sylvie stopped next to a classic red Stingray, a ’67.

“New wheels?”

“Borrowed.” Sylvie opened the driver-side door. “Toss your gear in the back. We’ve got a homecoming to celebrate.”

The Vette rumbled down Shoreline Drive. Mowed grass scented the air. Birds sang. Car horns honked. Sirens wailed. Kids shouted. Apartment-house windows flashed in the sunlight. Billboards and neon signs and traffic lights blazed a tumult of colors. I felt fragile, like I was being swept up in a typhoon of stimuli.

“You okay?” Sylvie asked, shooting me a concerned glance.

“Overwhelmed,” I answered.

“Bunkie says coming home from sea is like stepping from black-and-white into a rainbow.”

We crossed the High Street Bridge and swung south up the ramp to I-880.

“Hang on!” Sylvie announced. The Stingray took off in a blaze of acceleration. Sylvie drove like a pilot dodging Iraqi flak. We zigzagged lane to lane passing semi-trucks and buses and the late rush-hour traffic. I braced against the dashboard, my heart racing and my palms sweating, but it was more than just Sylvie’s driving that made my heart race. I had no plan, no job, no girl, no idea where life was taking me. I had failed to set the initial conditions. We barreled down the freeway heading God-knows-where and the sun had set and San Francisco across the bay vanished into a fog-shrouded night.

Before my dad committed suicide, he’d sometimes come to our room after my mom put my brother and me to bed. If he’d been drinking, he’d tell us stories about Nam: about punji stakes and booby-traps; how we dropped so many white phosphorus flares, it was never really night; how boom boom was what Vietnamese called sex; about crotch rot and jungle foot and LZ s and bouncing bettys. I remember the whiskey on his breath and I remember imagining a Vietnam where it was never night and where the people called sex by weird names. Dad always finished with the same story, about him coming home and how, as he waited in the airport for Mom, “long hairs spit on my boots.” I pictured him sitting there in the airport lounge in his starched Army uniform, wearing his Ranger’s beret and his black jump boots and then the “long hairs” spitting on him. The boots stood in the closet downstairs, as bright and black and shiny as they’d been the day he came home from Nam. “Boys,” he’d say, “that’s the thanks we got.” He’d shake his head. Then he’d pull the covers up to our chins, give us each a kiss, and he’d go back down where the lights were turned out and where he had his whiskey bottle and where he could lose himself to the night.

Sylvie and I exited the 880 south of Fremont and headed east. The area was unfamiliar to me – strip malls, fast-food franchises, discount shopping centers, U-Haul rentals, storage lockers, 7-11s – the detritus of American life.

Sylvie shot through an intersection as the light turned red.

“Where are we going?” I managed to ask, gripping the edge of my seat.

“I’m house-sitting,” she explained. “A dentist’s house.”

“Have I met the dentist?”

“You’ll meet him tonight.”

“You’re house sitting for somebody who’s home?”

“He travels a lot. He’s a Navy dentist.”

Gradually we climbed above the grid of malls and street lights and headlights. The air smelled of eucalyptus. We leaned around curves as Sylvie sped up a switchback road. The Stingray’s tires sang on the asphalt.

“What are you going to do,” Sylvie asked, “now that you’re out of the Navy?”

Find a woman like you, I thought. “Don’t know,” I said. “Travel around. Get a motorcycle.” Until that moment, I’d never considered getting a motorcycle.

“Bunkie never wants to go anywhere. He says he’s been everywhere in the Navy except home.”

I tended to agree with Bunkie.

“It’d be good to travel,” Sylvie said, as she braked into a carport.

I recognized Bunkie and Sylvie’s Volvo in the driveway. Cactus and spiny Yucca grew in a rock garden. From somewhere sprinklers were ratcheting. The house was all angles: glass, stone, and steel. Light blazed from picture windows. I hauled my sea bag out of the Stingray and followed Sylvie up the steps to an enormous mahogany door that was carved with intricate, abstract designs – it looked like a nest of snakes. Sylvie unlocked the door.

“We’re home!” she yelled.

“Yo!” a male voice answered.

The room was all white, the walls were white, the carpets were white, the sofas and stuffed chairs were white, the steel beams in the ceiling were white. Wrought-iron stairways spiraled up to the second floor and down to the basement. The wrought iron was white. Here and there were objects of Asian art – a Japanese print of a wave breaking in finger-like tendrils, a black and red kabuki mask, a bronze temple bell. One wall was covered with a painting of a woman with dozens of arms and a fiery, snake-head halo. A sculpture of a male torso in ebony wood stood inside the doorway. I heard the clank of metal striking metal in a steady, metronome beat.

“Let me introduce you to Karl.” Sylvie clanged down the spiral stairs.

The lower floor – I guess it was the basement – was an open room with barbells and dumbbells and mirrors and a Universal Gym. A door opened to a cedar-wood sauna. A man lay under the gym, pressing a chrome bar up and down. Each time the weights dropped, they sounded a bell-like knell.

“Just a sec,” the man said. “I got to finish this set.”

He wore blue Spandex shirt and shorts. His skin was tanned. His head was completely bald although he couldn’t have been older than thirty-five or forty. I watched him extend and collapse his arms. Sylvie and I waited silently for him to finish. He settled the weights gently and slid out from under the bar.

“This is Karl,” Sylvie said.

Karl reached out and wrung my hand. “Heard you were in the Gulf.” He fixed me with cavernous eyes, the eyes of a hawk. “We kicked some butt, didn’t we?”

We, I thought. What’s with “we?”

“You boys get acquainted. I’ll start dinner.” Sylvie kissed Karl’s cheek.

Karl peeled himself from his Spandex, dropping his shorts and shirt to the floor, apparently untroubled that he was standing in front of a stranger naked. He pulled a towel off a rack and wrapped it around his waist. I looked away.

“Care for a sauna?”

“No thanks.”

“I envy you. Being in a real battle. Nietzsche calls war the grand sagacity of every spirit; its curative power lies even in the wounds one receives.”

“No wounds,” I said. “Spent the war babysitting the ship’s reactors.”

“Physics.” Karl glanced up at the ceiling thoughtfully.

I followed his gaze. There were flecks in the plaster that sparkled in the light.

“We must be physicists to be creative since so far the codes and ideals have been constructed in ignorance of physics. Nietzsche said that too. The Kraut knows life.” Karl stepped into the sauna and sat down on a wooden bench with the towel draped across his lap. The sauna door was still open. I could feel the hot, dry air seeping into the room.

“You’re a dentist?” I said.

“That’s right.” From inside the sauna his voice sounded hollow and sepulchral.

“Sylvie says you’re away a lot.”

“Hawaii. Guam. Japan. Diego Garcia. You’d be surprised at who doesn’t practice dental hygiene. Take CINPAC. Commands the entire Pacific Fleet. Doesn’t floss!”

I wasn’t sure what was worse: Nietzsche or CINCPAC’s teeth.

“Let him go Karl,” Sylvie called from upstairs. “He’ll want to wash up.”

“You’ll be bunking on the main floor,” Karl said. “Sylvie’ll show you the way.” He swung the sauna door shut.

I clambered up the metal stairs.

Sylvie stood in front of an industrial-sized stove in a large kitchen. A wok simmered on a gas burner. Shrimp and pea shoots sautéed in the wok and the kitchen was filled with the fragrance of soy and hot sesame oil. The window behind the stove looked out over the canyon. There were a few houses here and there, most steel and concrete like Karl’s. Beyond the houses, the lights of Fremont and San Leandro and Oakland stretched into the night; the bridges, the San Mateo and the San Rafael, spanned the bay like headlight-beaded webs.

“Smells like heaven,” I said.

“There’s a beer in the fridge.” Sylvie stirred the sizzling wok with a wooden spoon.

“A Nietzsche-quoting dentist?”

Sylvie didn’t look up.

“Rich?”

“Family money,” Sylvie said.

“Sylvie,” I began, “what exactly is your situation here?”

“Get showered,” she answered. “Chow in thirty minutes. Towels on the bed.” She patted my cheek. “Don’t be late – the cook doesn’t like tardy victims.”

I hauled my stuff into the guest room.

But where Sylvie had touched my cheek, I felt a kind of cool, electric fizz. I was suddenly horny. How many months had it been? Nine? Ten? With Sharon. I’d remained true to Sharon. I’d wanted the initial conditions for our marriage to be perfect, without a flaw or blemish; I’d invested myself in celibacy (even if the investment hadn’t paid off). What’s more, what was going on with Sylvie and her Ubermensch dentist? What should I do about that?

The dining room was as cavernous as a mausoleum. A vast ebony-wood table stretched between us with Karl on one end and Sylvie on the other and me in the middle. Sylvie had placed candles in the center and turned the lights down and the candles flickered and cast shadows that danced across the walls like one of Karl’s creepy paintings. Across the table from me, against the white wall, was a statue of Kali, the Hindu goddess of destruction: skulls in her arms; legs contorted in a big-stepping dance. With the chilly room and the freaky statue and the spooky light I was losing my appetite. Karl wolfed his food. We drank a bottle of wine and another. Karl asked me questions about the war. I tried to answer but Karl knew more about the war than I did. He’d watched CNN and I’d only watched the ship’s reactors. I could tell Karl was disappointed. He wanted to hear about the “sagacity of war” or “the curative power of wounds.”

“So you quit the Navy,” he finally said. “And your woman left you?”

“Karl!” Sylvie slapped the table with the palm of her hand.

Karl waved her away. “The true man wants two things: danger and play. For that reason he wants woman, as the most dangerous plaything. Nietzsche said that.”

My face began to burn. I felt as if Karl had barged into a private room, where he didn’t belong, a room where I’d locked up my grief.

“Cool it,” Sylvie said.

“For the woman, the man is the means: the end is always the child. He said that too.”

“So much for the female fifty-one percent of humanity,” Sylvie said.

I wondered if Nietzsche was as big a prick as Karl.

Karl’s elbows were on the table and his chin was resting in his hands. Like he was posed as some kind of philosopher-king. He turned to face me, a weary smile on his face. “Your woman got religion. Right? Not much difference between religion and lust…”

“Let me guess,” Sylvie interrupted. “Nietzsche. Get your butt in the kitchen. Start the dishwasher.”

Karl laughed. “That’s my Sylvie! Resolves philosophy in a dishwasher.” He pushed his chair back, stood up, and padded into the kitchen.

For a minute, Sylvie faced me across the table.

I was angrier at her than I was at Karl. I’d told her about Sharon. She’d told Karl.

“I’m sorry,” she said.

“I think I’ll hit the sack.” I stood up.

“Do you want to talk?” she said.

I walked out of the room.

In the bedroom, I lay on the bed, the lights out. The moon had come up and a cold white light shown through the window. I thought of my dad and his war in Vietnam and how his war hadn’t been as tidy as my own. Every time our family moved, he’d carefully pack his souvenirs – the cracked photographs of buddies who’d been long dead, his honorable discharge, the North Vietnamese officer’s pistol he’d found. When we got to a new house, he’d arrange these things in a prominent place, on the fireplace mantle, on a living room bookshelf. Mother hated them. I can’t forget the war, he’d tell us. I’ll never forget it. He came home and he went to college and he got married but he used Vietnam to justify everything that went wrong in his life: his falling-apart marriage, his drinking too much, his many affairs with women. Once he attempted to explain his behavior to me. Son, he said, I’m living on borrowed time. I’m not going to take a chance I’ll miss anything. In the end, he missed everything.

Vietnam betrayed my dad and my dad betrayed my mother and Sharon betrayed me and Sylvie had betrayed my secrets to her dentist and she’d probably betrayed Bunkie as well. Was betrayal how it had to be? I lay in the bed brooding until I fell asleep.

I woke when I heard the bedroom door open. Sylvie stepped in and she closed the door behind her. In the moonlight, I watched her open her robe and I heard the rustle as her robe fell to the floor. Her skin was white– her breasts and belly and legs were white except for the darkness at the tips of her breasts. She leaned over me and she brushed her fingers over my lips. “Hush,” she whispered.

The darkness surrounded us and the night closed over us. We’re doing this, I thought, Sylvie and I are doing this. I thought of Bunkie and of Sharon and even of my dad. Then Sylvie raised herself above me and she arched her back and her head tipped back and I felt the heat where our bodies joined, hot and bright and I didn’t think of anything except Sylvie. It was too late. It was too late for Dad, too late for Sharon and Bunkie, too late to escape the night.

Afterwards, Sylvie cradled her head in the crook of my arm.

“How long have you been seeing Karl?” I whispered.

“I don’t see him. I housesit for him.”

“You don’t sleep with him?”

“I don’t think he sleeps with women.” For a moment she was silent. “I’m so lonely,” she whispered. “I just want someone to talk to.”

“Is he gay?”

I could feel Sylvie shrug.

“Is this about pity? Or about us? Or something else?” I whispered this as if I was whispering only to myself and I wasn’t sure she heard me.

Then she answered. “Isn’t it strange? We’re still young and we’re still sexy and if we love somebody in the Navy or if we’re in the Navy we go months without sex.” She placed her hand on my belly. She slipped her leg between mine. “I guess talk isn’t enough.”

I thought of Bunkie in the Gulf. It would be morning there, and the sun would have risen and the hot light would blaze off the sea. I thought of how Dad had finally killed himself, of how he’d blown his brains out in the living room of our house with his North Vietnamese officer’s pistol. I thought of his black-and-white snapshots of his dead buddies. I thought of his blood on the living-room rug. Was there an arc to these things? Was there a difference between day and night? Was betrayal inevitable? I heard the steady inhale and exhale of Sylvie’s breath. I lifted Sylvie’s leg and swung out of bed, taking care not to wake her. I put on my running shorts and shoes, and slipped out the bedroom door. I walked across the empty expanse of Karl’s living room. I opened the front door. I could see the entire peninsula below the house and the fog had lifted and the lights shone all the way to San Francisco like jewels on a black cloak. The air was dry but I could smell things growing: the grasses, the eucalyptus. A full moon cast a light purer than daylight.

I began to jog, following the road uphill, beyond Karl’s house. The grass at the crest of the hill had been blackened by wildfire. I could see the line where the fire had stopped. Except for the sound of my feet, it was silent -- no birdsong, no crickets. I fell into the rhythm of running, listening to the sound of my breathing, to the beat of my heart, but I was straining to hear something else, but what I heard was only silence.