The First

Karl Miller

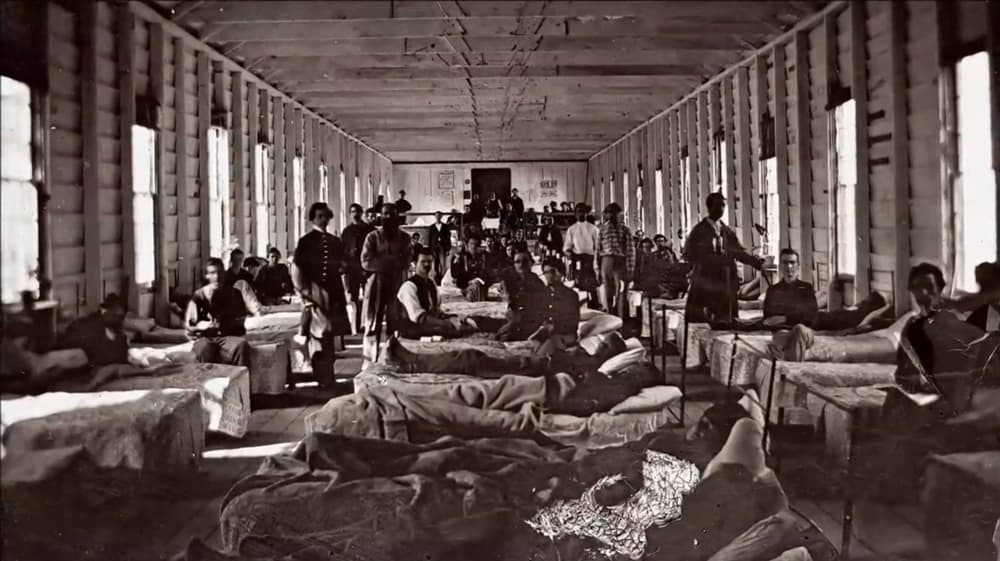

Florida State Hospital, Chattahoochee, FL, 1876

The old doctor – white-haired, bespectacled, stoop-shouldered – leads his thin, serious protégé toward the first in a row of patients on the second floor.

The bed gives its occupant a view of the sunlit courtyard but she herself rests in shadows.

“Good morning, Miss Munroe,” the old doctor begins. “This is Doctor Lenoir. You are his very first patient, so be nice.”

“Aren’t I always nice?” she drawls weakly but flirtatiously. Her voice has a hollow quality to it due to air moving through the place her nose had been.

“Well, some days more than others,” the doctor says, and starts to open his notebook when an orderly approaches urgently.

“Doctor, emergency on the first floor.”

The old man gives an exasperated sigh and turns to Lenoir. “Check on the progress of her disease.” He pauses, and whispers “Carefully,” then follows the orderly.

The young doctor stands for a moment, looking down at a blank page in his notebook.

“Are you old enough to be doing this?” she asks.

He looks up into two intensely blue eyes that are surrounded by a field of reddish lesions.

“Yes. Yes, m’am,” he stammers. “Attended medical school in New Orleans for two years.”

“So you missed the war?”

“Yes, I was too young to have the chance to serve.”

“Well, you sure were lucky on that score.”

He looks down at his notebook again.

“I think you’re supposed to be checking the progress of the disease?”

“Is that all right?”

“Sure. It’s making wonderful progress,” she says with a weak laugh that turns into a fit of coughing and ends in red sputum on a small handkerchief she produces from below the sheets.

The doctor motions to an orderly who pulls a screen into place.

The patient briefly raises the sheet. The doctor looks, unable to hide a grimace.

“Can you believe that wasteland was once so enticing soldiers would spend a month’s wages for the pleasure?” She reaches to a rosewood nightstand next to the bed and picks up a black bottle with a faded flower on it. The patient sprays around them and winces as the perfume settles onto broken skin.

The doctor begins writing.

“Well?”

He looks at her directly. “What did the last doctor say?”

“A week – maybe. Maybe a month.”

He nods solemnly. “I can’t say I disagree.” A pause. “Is there anyone we can contact for you?”

She makes a small smile, reaches to the nightstand for an ornate silver oval picture frame and turns it toward the doctor. A girl in her mid-teens wearing an elegant dress looks out tentatively. Her dark hair is tied in a bow to one side; her hands rest in her lap.

“My boyfriend would write the most beautiful letters, talking about the battles and how much he thought about me. When he finally came home on leave – right after Petersburg – we got swept up in the time. After that, he stopped writing all those beautiful letters. And when I began to show, my father threw me out - with my mother’s blessing.”

She pauses and takes a sip of water from a glass on the table.

“A sweet man – I thought – came to my aid after I lost the baby. He had such perfect manners. After a time, I let him in and then he had me join the rest of the girls at The Elysian. That was an elegant place – entertaining the best Atlanta had to offer. I was the favorite – for a while. Then there were other, newer girls, and after a time, I was sent to another house, with not such nice gentlemen, and, after some time there, to another that was even worse. I got sick then and they turned me out. Some nuns arranged for me to come here. So – no one,” she finishes.

The doctor is quiet. He stares at the picture for a full ten seconds.

“Well, doctor,” she says, her flirtatious tone returning as the moment breaks, “don’t get obsessed -- you’re too late for her.”

Before Lenoir can ask anything else, the old doctor returns. “Damned orderlies,” he mutters and pulls the young doctor toward the next bed.

Three days later, a nurse knocks on the Lenoir’s office door. He looks up from the stack of files on his desk.

“Excuse me, doctor. Miss Munroe died last night. She asked that I give this to you,” she says, handing over the silver-framed picture and departing.

The doctor sits at the desk and looks at the girl for a long moment. With his index finger, he traces the outline of a perfect face, breathes in deeply and exhales.

* * *

In Forgotten Memories on Las Olas in Fort Lauderdale, a matronly woman walks past a pair of Gilded Age marble busts and picks up an objet d’art. The proprietor of the antique store, watching surreptitiously, swiftly approaches.

“We just acquired that in an estate auction.”

“It’s a nice frame,” the woman says, “but a bit damaged,” she adds, emphasizing a bit of tarnish on the bottom edge.

“It is a nice piece. A steal at $75. Dates from the mid-1800s. The owner was the last in a line of doctors going back over a hundred years. Great-grandfather, grandfather, father and the son, who died childless.” She looks at the girl in the picture. “I have no idea who that was. Maybe the wife of one of the ancestors?”

“I just need the frame.” The tone says she’s not in the mood for chit-chat. “Could you take the picture out for me?”

“Certainly,” the owner responds. She brings the frame to the sales counter, turns it over and manipulates hinges on the back until it opens. The picture sticks momentarily, but it finally gives way. She drops the photo into a can, it landing in such a way that, to someone passing, a young girl’s face shows amid the other discarded things.

Karl Miller

Florida State Hospital, Chattahoochee, FL, 1876

The old doctor – white-haired, bespectacled, stoop-shouldered – leads his thin, serious protégé toward the first in a row of patients on the second floor.

The bed gives its occupant a view of the sunlit courtyard but she herself rests in shadows.

“Good morning, Miss Munroe,” the old doctor begins. “This is Doctor Lenoir. You are his very first patient, so be nice.”

“Aren’t I always nice?” she drawls weakly but flirtatiously. Her voice has a hollow quality to it due to air moving through the place her nose had been.

“Well, some days more than others,” the doctor says, and starts to open his notebook when an orderly approaches urgently.

“Doctor, emergency on the first floor.”

The old man gives an exasperated sigh and turns to Lenoir. “Check on the progress of her disease.” He pauses, and whispers “Carefully,” then follows the orderly.

The young doctor stands for a moment, looking down at a blank page in his notebook.

“Are you old enough to be doing this?” she asks.

He looks up into two intensely blue eyes that are surrounded by a field of reddish lesions.

“Yes. Yes, m’am,” he stammers. “Attended medical school in New Orleans for two years.”

“So you missed the war?”

“Yes, I was too young to have the chance to serve.”

“Well, you sure were lucky on that score.”

He looks down at his notebook again.

“I think you’re supposed to be checking the progress of the disease?”

“Is that all right?”

“Sure. It’s making wonderful progress,” she says with a weak laugh that turns into a fit of coughing and ends in red sputum on a small handkerchief she produces from below the sheets.

The doctor motions to an orderly who pulls a screen into place.

The patient briefly raises the sheet. The doctor looks, unable to hide a grimace.

“Can you believe that wasteland was once so enticing soldiers would spend a month’s wages for the pleasure?” She reaches to a rosewood nightstand next to the bed and picks up a black bottle with a faded flower on it. The patient sprays around them and winces as the perfume settles onto broken skin.

The doctor begins writing.

“Well?”

He looks at her directly. “What did the last doctor say?”

“A week – maybe. Maybe a month.”

He nods solemnly. “I can’t say I disagree.” A pause. “Is there anyone we can contact for you?”

She makes a small smile, reaches to the nightstand for an ornate silver oval picture frame and turns it toward the doctor. A girl in her mid-teens wearing an elegant dress looks out tentatively. Her dark hair is tied in a bow to one side; her hands rest in her lap.

“My boyfriend would write the most beautiful letters, talking about the battles and how much he thought about me. When he finally came home on leave – right after Petersburg – we got swept up in the time. After that, he stopped writing all those beautiful letters. And when I began to show, my father threw me out - with my mother’s blessing.”

She pauses and takes a sip of water from a glass on the table.

“A sweet man – I thought – came to my aid after I lost the baby. He had such perfect manners. After a time, I let him in and then he had me join the rest of the girls at The Elysian. That was an elegant place – entertaining the best Atlanta had to offer. I was the favorite – for a while. Then there were other, newer girls, and after a time, I was sent to another house, with not such nice gentlemen, and, after some time there, to another that was even worse. I got sick then and they turned me out. Some nuns arranged for me to come here. So – no one,” she finishes.

The doctor is quiet. He stares at the picture for a full ten seconds.

“Well, doctor,” she says, her flirtatious tone returning as the moment breaks, “don’t get obsessed -- you’re too late for her.”

Before Lenoir can ask anything else, the old doctor returns. “Damned orderlies,” he mutters and pulls the young doctor toward the next bed.

Three days later, a nurse knocks on the Lenoir’s office door. He looks up from the stack of files on his desk.

“Excuse me, doctor. Miss Munroe died last night. She asked that I give this to you,” she says, handing over the silver-framed picture and departing.

The doctor sits at the desk and looks at the girl for a long moment. With his index finger, he traces the outline of a perfect face, breathes in deeply and exhales.

* * *

In Forgotten Memories on Las Olas in Fort Lauderdale, a matronly woman walks past a pair of Gilded Age marble busts and picks up an objet d’art. The proprietor of the antique store, watching surreptitiously, swiftly approaches.

“We just acquired that in an estate auction.”

“It’s a nice frame,” the woman says, “but a bit damaged,” she adds, emphasizing a bit of tarnish on the bottom edge.

“It is a nice piece. A steal at $75. Dates from the mid-1800s. The owner was the last in a line of doctors going back over a hundred years. Great-grandfather, grandfather, father and the son, who died childless.” She looks at the girl in the picture. “I have no idea who that was. Maybe the wife of one of the ancestors?”

“I just need the frame.” The tone says she’s not in the mood for chit-chat. “Could you take the picture out for me?”

“Certainly,” the owner responds. She brings the frame to the sales counter, turns it over and manipulates hinges on the back until it opens. The picture sticks momentarily, but it finally gives way. She drops the photo into a can, it landing in such a way that, to someone passing, a young girl’s face shows amid the other discarded things.