Feelin' Guruvy

Lenny Levine

She was handing out leaflets in front of the Fillmore East after the Zappa concert.

“I’d buy whatever she’s selling,” my friend Howie remarked.

She had a beautiful, childlike face and long brown hair that fell to her waist. Her jeans were skin-tight and her halter top was almost nonexistent.

“Swami Nindak at midnight tonight,” she was saying in a breathy voice. “Come and experience the wisdom of Swami Nindak.”

“Who’s he?” I asked as I took one of her flyers.

“Someone who will completely change your life,” she said as she looked into my eyes. The effect was startling.

“Will you be there?” I blurted out.

“Of course. Will you?”

“Sure,” I said without hesitation, as Howie snickered.

“Well, that’s good, then.” She gave me a dazzling smile. “I’ll see you.” She resumed wending her way through the crowd. “Swami Nindak at midnight tonight. Swami Nindak.”

“Man, Kevin, you are unbelievable!” Howie shook his head. “Are you really gonna waste your time on that bullshit?”

“Maybe,” I said, checking the address, which was only a block away. “What do I have to lose?”

“Oh, I don’t know, your money, your self-respect, your girlfriend?”

“Ah. Well, we don’t have to worry about that last item.”

He gave me a sideways glance. “You and Annabel broke up again? How many times does that make?”

“Three, maybe four.”

“Well, I predict you’ll hit double digits, before you finally get married and divorced.”

He glanced over at the girl with the flyers, who was talking to three bearded guys in dashikis. “In the meantime, you do realize you’ve got zero chance of making it with Mahatma Hottie over there, don’t you?”

“You never know,” I said.

“Just out of curiosity, why did you and Annabel break up this time?”

“She was pissed off at me for wanting to go to this concert. She said she hates Frank Zappa and everything he represents.”

Howie’s eyes widened. “Wow! I know her parents are huge supporters of the Tricky Dickster, but I didn’t realize it was hereditary.”

I could feel the magic of the musical performance I’d just witnessed vanishing.

“Look, she’s not as extreme as her parents, but she doesn’t approve of what she calls the ‘counterculture lifestyle.’ Can we not talk about this?”

“Fine with me. So you’re really gonna follow your libido down the yellow brick road to Swami Nincompoop?”

“Nindak,” I said, looking at the flyer and then at my watch. “It starts at midnight, so I have a half hour to kill. You wanna go have a drink someplace?”

“Nah.” He looked around sourly. “I think I’ll just go home and burn my guitar in the fireplace because I’ll never be able to play like that.”

“That’s the spirit,” I said.

Howie looked at me with faux sadness.

“They’ll probably kidnap you and put you in an ashram, so this might be the last time I ever see you. So have a nice life and several more!”

He waggled his fingers, then joined the crowd of people walking up Second Avenue toward East Sixth. I could hear him in their midst, singing the lyrics from Zappa’s “Who Needs the Peace Corps?” at the top of his lungs.

“Every town must have a place where phony hippies meet.

Psychedelic dungeons popping up on every street.”

We’ll see, I thought.

~ ~ ~

The address was a brownstone on East Fifth, and the event was evidently taking place in a first-floor apartment. As I approached the front stoop, it seemed to be well underway. I could hear chanting coming through a large bay window. It was mostly male voices, and they were rapidly repeating something that sounded like “salrig, salrig, salrig.”

The magical mystery flyer girl was standing in the doorway at the top of the steps, greeting new arrivals, which at the moment consisted of me.

“Hi, I thought I came early,” I said. “Did I get the time wrong? I thought it wasn’t starting ’til midnight.”

“No one can ever get the time wrong,” she said with a knowing smile. “Whatever time it is, that’s the time it was meant to be. But welcome, er…” She looked at me questioningly.

“Kevin,” I said.

“Kevin,” she repeated. It sounded nice.

I ventured, “And your name is…?”

“Luna. Please make yourself at home, Kevin. Swami Nindak will be here at midnight.”

“Great. I’m glad I didn’t miss anything.”

“Nothing is ever missed because everything was meant to be.”

“Well, that’s reassuring,” I said. “By the way, what are they chanting in there, ‘salrig, salrig’? Is that some kind of word in Hindi or Sanskrit?”

She giggled. “Is that what you think?”

“I don’t know what to think.”

She giggled again, a soft, melodious sound. “It’s English. But it blurs together when it’s said quickly, which is how it must be said. They’re chanting, ‘It’s all rigged. It’s all rigged.’”

She looked at me the way she had in front of the Fillmore, to the same effect.

“It’s one of our mantras,” she said softly.

“I’ve never heard a mantra like that.”

Again, the knowing smile.

“You will hear many things tonight that you’ve never heard.”

She looked over my shoulder. I did too, and saw a couple coming up the steps behind me. So I knew that was it.

“Well, thanks,” I said lamely.

“It is my duty.” She waved to the couple. “Welcome!”

I stepped through the doorway into a large vestibule, and into the attentions of a tall guy with a bushy red beard. He was dressed in a flowing white robe.

“Welcome,” he said, extending his hand, which I shook tentatively. “My name is Laal, and yours is…?”

“Kevin.”

“Kevin,” he repeated. It didn’t sound as good as when she said it. “We’re glad you came.”

The chanting was going on in the next room. I could hear it through the door, louder and more insistent than it had sounded from the street. They were no longer saying “salrig, salrig.” They’d changed it to something like “dombisuka, dombisuka.”

“I’m interested in those chants,” I told Laal. “Luna told me what the other one was, but what are they saying now?”

“It’s one of our most important chants, a core teaching. They’re chanting ‘Don’t be a sucker. Don’t be a sucker.’”

That did it. That was the final straw for me.

“Is this Candid Camera?” I said, looking around me. “This is a put-on, right? What kind of place is this? Who are you people?”

He gave me a wide grin through the chin whiskers.

“We are disciples of Swami Nindak. We are believers in Transcendental Cynicism.”

He reached into his robe, withdrew a pamphlet, and handed it to me. There was a list of mantras on the first page, phrases like they all do it, it’s a fix, don’t be fooled, and they’re liars, as well as the aforementioned it’s all rigged and don’t be a sucker. There must have been twenty-five in all.

“We chant them in that order,” he told me. “Then we go back to the top. Want to give it a try?”

Through the door, I could hear them repeating “they all do it,” which sounded like “thyalldoot, thyalldoot.”

In for a penny, in for a pound, I decided.

“What do I do?” I asked Laal. “Just walk in there?”

“That’s right. Take a seat on the floor, anywhere you’d like. Some people prefer the lotus position, but it’s not mandatory.”

That was good to hear. I was never what you’d call supple, and I couldn’t stay in a lotus position for even two seconds.

“I won’t be interrupting anything, will I?”

Again, the wide grin. “On the contrary, you’ll be enhancing it.”

He opened the door, and I stepped into a large room whose floor was covered in rugs and cushions. About thirty men and a few women sat facing the front of the room, where a man stood. He was sporting the same type of robe as Laal’s, and he didn’t seem to notice my entrance because his eyes were shut, as were everyone else’s.

I quietly sat down in an unoccupied area and checked the list. They’d moved on to it’s a fix, which sounded like “tsafix, tsafix, tsafix,” so I closed my eyes and joined in.

I’d barely begun when the guy at the front clapped his hands together three times. Without missing a beat, they switched to don’t be fooled, or “dombifool, dombifool.” I did likewise.

We chanted it for maybe five minutes, as I struggled not to feel ridiculous; then he clapped his hands again three times. I’d already snuck a peek at the list, so I knew it was going to be they’re liars.

I boldly made the switch, right in sync, and felt pretty good about it. “Thrliars, thrliars, thrliars,” I chanted as I started to get into it.

This chant seemed to last longer than the others; at least that’s how it felt. By the time they got to the next switch of mantra, I was sort of floating inside my head. The words became meaningless sounds as I watched the backs of my eyelids. It was very peaceful.

Then it all changed. To this day, I don’t know why. I remember hearing the three claps, opening my eyes to check the list, shutting them again, and switching with the others to they’re full of shit (“thrfullashit, thrfullashit”).

It was either that particular chant or the accumulation, but I suddenly had an epiphany.

Yeah, that’s right, said a voice inside me, that’s fuckin’-A right! They’re full of shit. All of them, everybody. There wasn’t a single person I knew or had ever known who wasn’t, in some way, completely full of shit. Why hadn’t I ever seen it?

I squeezed my eyes even tighter and really dug in. “Thrfullashit, thrfullashit, thrfullashit.” I was actually growling, and possibly drooling.

The chant changed again, to screw them all. I didn’t even have to check the list; I just knew it.

“Screwemall, screwemall, screwemall,” I intoned, my voice getting louder as my anger ratcheted up toward rage.

“Screwemall! Screwemall! Screwem…”

“Silence!” the guy at the front bellowed.

It was almost like a physical slap in the face. My eyes popped open.

The man in the robe was no longer alone. Standing next to him was a shorter man in a robe.

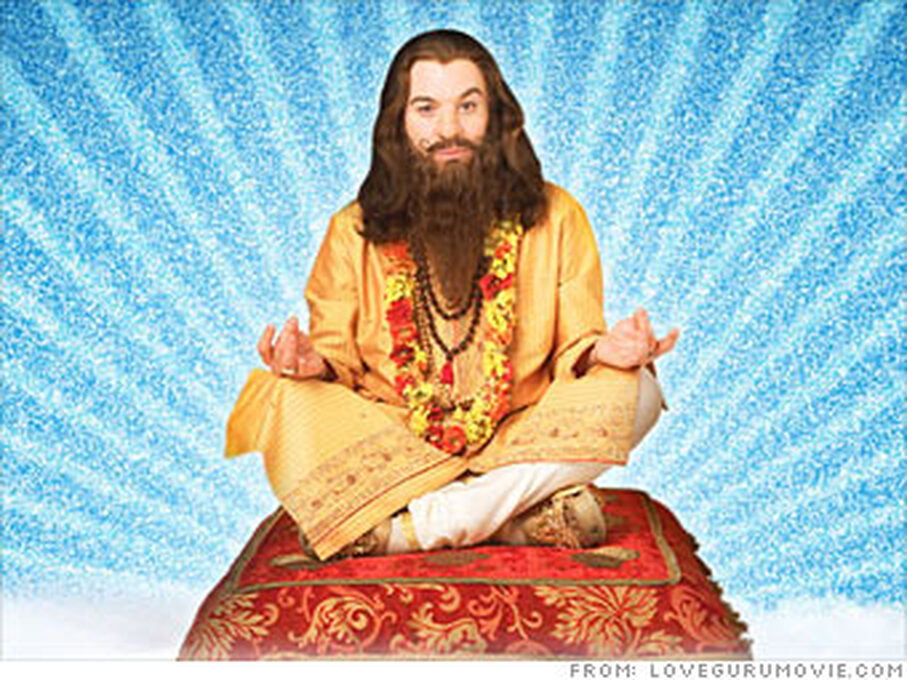

“I am Swami Nindak,” he announced with a shy smile.

My insides were still vibrating from all that emotion as I stared at him. My hands were balled into fists, and my stomach wanted to heave. I had no idea why.

He gazed tranquilly about the room, taking in everyone. When he got to me, his eyes seemed to twinkle.

“I see an angry face,” he said in a singsong Indian accent. “That is good. That is very good.”

His gaze moved on until it had covered the entire room. Then he nodded.

“Many of you are familiar with me and my teachings, but some are not, so I will explain: I am not holy and I am not wise. I am merely a vessel, as is every human being. Contained in me, as in all of us, is a potent, universal force: the power of Transcendental Cynicism.”

His fingers were long and delicate. He kept running them through his gray, scraggly beard like a comb, breaking up the tangles. Ordinarily, I would have found this annoying, if not disgusting, but now I found it fascinating.

I glanced around me at the people, noticing their calm, attentive expressions. Had I been the only one with an angry face? And why did he seem to approve of it?

“What is Transcendental Cynicism? It is simply the awareness of fault. There is fault in everything. Perfection does not exist in this world, and seeking it will only end in grief and frustration. The only true path is to recognize that fault exists in everyone and everything. And that it is our duty to find it.”

I’d never heard anything like this, but it resonated with me. All my life I thought I’d been looking for perfection, not settling for the ordinary, following my dreams. But what had it gotten me? A couple of years in a mediocre bar band? A dead-end job in a record store at age twenty-six? A girlfriend I not only did not love, but wasn’t even sure I liked? A girlfriend I couldn’t break up with unless she did it first, over and over?

But maybe my dreams never existed in the first place. Maybe they were just delusions, a colossal waste of time. In that moment it all made perfect sense. My life, as I was living it, was nothing but a colossal waste of time.

“When one discovers fault,” Swami Nindak was saying in his gentle, beguiling voice, “it is not a pleasant experience. It can make one very angry, which is a natural reaction. That is why I am gratified to see angry faces among my followers. It means that they sense the truth, that they understand.”

Boy, did I understand. My fists were still clenched, and I could feel my fingernails digging into my palms.

“But anger is not the goal,” he said. “In fact, it is just the opposite. Anger is the impediment.”

He cocked his head in sly rebuke. I felt immediate, inexplicable shame.

“Anger is what we must transcend. That is why we say our philosophy is ‘transcendental.’ We must surmount our emotions and rise above the dark clouds of anger. We must cut through them, and soar into the clear light of cynicism.”

My eyes filled with tears, because I knew just as sure as I was sitting there that I could never do it. How can anyone recognize that his existence is a meaningless sham and not be wild-eyed, rip-shit furious about it? It seemed impossible.

“It may seem impossible,” Swami Nindak said, freaking me out even more, “but it is not. It is extremely daunting and may take years to accomplish, but it is not impossible. It is a goal we can achieve.

“There is a mantra that can be helpful. It consists of two words: ‘so what?’ Will you join me now in chanting it?”

I tried to clear my mind as I closed my eyes and began chanting “sowat, sowat, sowat” for all I was worth.

It seemed to be working. Yeah, so what? said that inner voice. If it doesn’t really matter, only an idiot would get pissed off about it. It’s not worth your energy.

My anger was diminishing, but it still lurked in the background. It’s the hardest thing in the world to let go of your anger. But it was joined now by a new feeling, a sort of positive fatalism. If it is what it is, then that’s how it is. And so what?

The chant continued for I don’t know how long. Then Swami Nindak said, “Silence.”

He didn’t bellow it like the other guy; he almost whispered it. But it still got through.

I opened my eyes and gazed at his smiling face.

“Do you see?” he asked, looking around the room.

I saw.

“And now,” he continued, “I’m afraid we must end our little gathering for the present. For those who are newcomers, I hope the experience was meaningful and that I will see you again on our next occasion. For those who are acolytes, I hope I have helped to advance your progress in the journey.”

All about me I could sense heads nodding.

“Let us conclude, then, with one final mantra. It is perhaps the most important. That is why you will find it at the very top of your list.”

I did a quick check to see what it was. I hadn’t noticed before, but the words to this one were actually in bold type. It said, “Not necessarily.”

I closed my eyes again and gave myself to it. “Notnecessarily, notnecessarily, notnecessarily.” Of all the chants, this seemed to be the only one whose sounds didn’t mush together when you said them quickly. They sounded clear and like themselves.

“Notnecessarily, notnecessarily, notnecessarily.”

I could have chanted it forever.

~ ~ ~

It was nearly 2 a.m. as I walked in a semi-daze toward the building that housed my shoebox apartment. I was thinking about what I could do with this newfound insight, or even if I could do anything. One thing for sure, I was going back there again the next night.

The only downside of the evening was that Luna and Laal turned out to be an item. I saw them kissing in the vestibule as I was leaving. Oh, well, so what?

As I neared my building, I saw the figure of a woman sitting on the steps in front of the entrance. She was huddled over a book that she was reading by flashlight, and could only be one person. Annabel.

She looked up at me as I approached and gave a soft, embarrassed laugh.

“I haven’t been sitting here the whole time. The coffee shop closed at one, so it’s just been an hour.” She began to cry. “I’m sorry, I’m so, so sorry.”

I took her in my arms and held her.

“It’s okay,” I said. “Come inside.”

I mean, what else could I do?

We got to the apartment and she clung to me. She said she’d been miserable because she understood now how wrong she’d been. How badly she’d treated me.

“I don’t know what I was thinking; it was just stupid politics,” she said, weeping against my shoulder. “You’re wonderful, you’re intelligent, you care for humanity. I love you.”

I held her closer but didn’t say anything in reply. She raised her head and looked into my eyes.

“That’s okay,” she said. “I deserve it.”

She sat down on the bed, which took up most of the space in the apartment, and I made us some coffee on my hot plate.

“How was Frank Zappa?” she asked. “I don’t really hate him. I know he’s a genius. I was just being a bitch.”

“He was amazing,” I said, sitting down next to her and handing her a mug. “But even more amazing was what happened afterward.”

I told her the whole story, minus Luna’s part in it, and her eyes grew big.

“Transcendental Cynicism!” she said in wonder. “I’ve never heard of such a thing.”

“They gave me this pamphlet,” I said, pulling it out of my jeans pocket.

She leafed through it. Annabel is a very quick reader.

“So, there is fault in everyone and everything. Perfection is impossible, and we must find fault. Is that right?”

“Yeah,” I said, “but you make it sound negative. When you chant, you see how positive it is. The experience is electric. It’s coming face-to-face with reality.”

She thought about it for a moment.

“Then there must be something wrong with Transcendental Cynicism, right?”

“I’m not sure I understand,” I said.

“If there’s fault in everything, then there must be fault in Transcendental Cynicism.”

“I…”

She put down her coffee mug and wrapped her arms around me.

“Never mind, don’t listen to me; I was just being terrible again. You had a profound experience. That’s a lot more than I could ever say for myself. You’re an incredible man, and I don’t appreciate you nearly enough. But I’ll try to, Kevin, I swear I will.”

We kissed.

Making love felt as astonishing as ever. As its passion grew I realized how precious she was to me, how lucky I was to have her.

And the intensity I’d felt during those chants was already fading into memory, because she was right. Transcendental Cynicism must have faults, by definition.

“Don’t be fooled, don’t be fooled,” I’d chanted, but maybe one of the things I shouldn’t be fooled by was Transcendental Cynicism.

If there is fault in everyone and everything, and if one of the faults with Transcendental Cynicism is that it doesn’t include a smart, beautiful woman who loves me, then who needs it?

“I love you,” said Annabel, simultaneous with my thought.

“I love you too,” I whispered. And I did, I really did, with every fiber of my being.

We lost ourselves in the sensuous rhythm. Time seemed suspended, which is why I don’t know when it was that I realized what had been going through my head all along, perfectly and relentlessly in sync with our lovemaking.

It was “notnecessarily, notnecessarily, notnecessarily.”

Lenny Levine

She was handing out leaflets in front of the Fillmore East after the Zappa concert.

“I’d buy whatever she’s selling,” my friend Howie remarked.

She had a beautiful, childlike face and long brown hair that fell to her waist. Her jeans were skin-tight and her halter top was almost nonexistent.

“Swami Nindak at midnight tonight,” she was saying in a breathy voice. “Come and experience the wisdom of Swami Nindak.”

“Who’s he?” I asked as I took one of her flyers.

“Someone who will completely change your life,” she said as she looked into my eyes. The effect was startling.

“Will you be there?” I blurted out.

“Of course. Will you?”

“Sure,” I said without hesitation, as Howie snickered.

“Well, that’s good, then.” She gave me a dazzling smile. “I’ll see you.” She resumed wending her way through the crowd. “Swami Nindak at midnight tonight. Swami Nindak.”

“Man, Kevin, you are unbelievable!” Howie shook his head. “Are you really gonna waste your time on that bullshit?”

“Maybe,” I said, checking the address, which was only a block away. “What do I have to lose?”

“Oh, I don’t know, your money, your self-respect, your girlfriend?”

“Ah. Well, we don’t have to worry about that last item.”

He gave me a sideways glance. “You and Annabel broke up again? How many times does that make?”

“Three, maybe four.”

“Well, I predict you’ll hit double digits, before you finally get married and divorced.”

He glanced over at the girl with the flyers, who was talking to three bearded guys in dashikis. “In the meantime, you do realize you’ve got zero chance of making it with Mahatma Hottie over there, don’t you?”

“You never know,” I said.

“Just out of curiosity, why did you and Annabel break up this time?”

“She was pissed off at me for wanting to go to this concert. She said she hates Frank Zappa and everything he represents.”

Howie’s eyes widened. “Wow! I know her parents are huge supporters of the Tricky Dickster, but I didn’t realize it was hereditary.”

I could feel the magic of the musical performance I’d just witnessed vanishing.

“Look, she’s not as extreme as her parents, but she doesn’t approve of what she calls the ‘counterculture lifestyle.’ Can we not talk about this?”

“Fine with me. So you’re really gonna follow your libido down the yellow brick road to Swami Nincompoop?”

“Nindak,” I said, looking at the flyer and then at my watch. “It starts at midnight, so I have a half hour to kill. You wanna go have a drink someplace?”

“Nah.” He looked around sourly. “I think I’ll just go home and burn my guitar in the fireplace because I’ll never be able to play like that.”

“That’s the spirit,” I said.

Howie looked at me with faux sadness.

“They’ll probably kidnap you and put you in an ashram, so this might be the last time I ever see you. So have a nice life and several more!”

He waggled his fingers, then joined the crowd of people walking up Second Avenue toward East Sixth. I could hear him in their midst, singing the lyrics from Zappa’s “Who Needs the Peace Corps?” at the top of his lungs.

“Every town must have a place where phony hippies meet.

Psychedelic dungeons popping up on every street.”

We’ll see, I thought.

~ ~ ~

The address was a brownstone on East Fifth, and the event was evidently taking place in a first-floor apartment. As I approached the front stoop, it seemed to be well underway. I could hear chanting coming through a large bay window. It was mostly male voices, and they were rapidly repeating something that sounded like “salrig, salrig, salrig.”

The magical mystery flyer girl was standing in the doorway at the top of the steps, greeting new arrivals, which at the moment consisted of me.

“Hi, I thought I came early,” I said. “Did I get the time wrong? I thought it wasn’t starting ’til midnight.”

“No one can ever get the time wrong,” she said with a knowing smile. “Whatever time it is, that’s the time it was meant to be. But welcome, er…” She looked at me questioningly.

“Kevin,” I said.

“Kevin,” she repeated. It sounded nice.

I ventured, “And your name is…?”

“Luna. Please make yourself at home, Kevin. Swami Nindak will be here at midnight.”

“Great. I’m glad I didn’t miss anything.”

“Nothing is ever missed because everything was meant to be.”

“Well, that’s reassuring,” I said. “By the way, what are they chanting in there, ‘salrig, salrig’? Is that some kind of word in Hindi or Sanskrit?”

She giggled. “Is that what you think?”

“I don’t know what to think.”

She giggled again, a soft, melodious sound. “It’s English. But it blurs together when it’s said quickly, which is how it must be said. They’re chanting, ‘It’s all rigged. It’s all rigged.’”

She looked at me the way she had in front of the Fillmore, to the same effect.

“It’s one of our mantras,” she said softly.

“I’ve never heard a mantra like that.”

Again, the knowing smile.

“You will hear many things tonight that you’ve never heard.”

She looked over my shoulder. I did too, and saw a couple coming up the steps behind me. So I knew that was it.

“Well, thanks,” I said lamely.

“It is my duty.” She waved to the couple. “Welcome!”

I stepped through the doorway into a large vestibule, and into the attentions of a tall guy with a bushy red beard. He was dressed in a flowing white robe.

“Welcome,” he said, extending his hand, which I shook tentatively. “My name is Laal, and yours is…?”

“Kevin.”

“Kevin,” he repeated. It didn’t sound as good as when she said it. “We’re glad you came.”

The chanting was going on in the next room. I could hear it through the door, louder and more insistent than it had sounded from the street. They were no longer saying “salrig, salrig.” They’d changed it to something like “dombisuka, dombisuka.”

“I’m interested in those chants,” I told Laal. “Luna told me what the other one was, but what are they saying now?”

“It’s one of our most important chants, a core teaching. They’re chanting ‘Don’t be a sucker. Don’t be a sucker.’”

That did it. That was the final straw for me.

“Is this Candid Camera?” I said, looking around me. “This is a put-on, right? What kind of place is this? Who are you people?”

He gave me a wide grin through the chin whiskers.

“We are disciples of Swami Nindak. We are believers in Transcendental Cynicism.”

He reached into his robe, withdrew a pamphlet, and handed it to me. There was a list of mantras on the first page, phrases like they all do it, it’s a fix, don’t be fooled, and they’re liars, as well as the aforementioned it’s all rigged and don’t be a sucker. There must have been twenty-five in all.

“We chant them in that order,” he told me. “Then we go back to the top. Want to give it a try?”

Through the door, I could hear them repeating “they all do it,” which sounded like “thyalldoot, thyalldoot.”

In for a penny, in for a pound, I decided.

“What do I do?” I asked Laal. “Just walk in there?”

“That’s right. Take a seat on the floor, anywhere you’d like. Some people prefer the lotus position, but it’s not mandatory.”

That was good to hear. I was never what you’d call supple, and I couldn’t stay in a lotus position for even two seconds.

“I won’t be interrupting anything, will I?”

Again, the wide grin. “On the contrary, you’ll be enhancing it.”

He opened the door, and I stepped into a large room whose floor was covered in rugs and cushions. About thirty men and a few women sat facing the front of the room, where a man stood. He was sporting the same type of robe as Laal’s, and he didn’t seem to notice my entrance because his eyes were shut, as were everyone else’s.

I quietly sat down in an unoccupied area and checked the list. They’d moved on to it’s a fix, which sounded like “tsafix, tsafix, tsafix,” so I closed my eyes and joined in.

I’d barely begun when the guy at the front clapped his hands together three times. Without missing a beat, they switched to don’t be fooled, or “dombifool, dombifool.” I did likewise.

We chanted it for maybe five minutes, as I struggled not to feel ridiculous; then he clapped his hands again three times. I’d already snuck a peek at the list, so I knew it was going to be they’re liars.

I boldly made the switch, right in sync, and felt pretty good about it. “Thrliars, thrliars, thrliars,” I chanted as I started to get into it.

This chant seemed to last longer than the others; at least that’s how it felt. By the time they got to the next switch of mantra, I was sort of floating inside my head. The words became meaningless sounds as I watched the backs of my eyelids. It was very peaceful.

Then it all changed. To this day, I don’t know why. I remember hearing the three claps, opening my eyes to check the list, shutting them again, and switching with the others to they’re full of shit (“thrfullashit, thrfullashit”).

It was either that particular chant or the accumulation, but I suddenly had an epiphany.

Yeah, that’s right, said a voice inside me, that’s fuckin’-A right! They’re full of shit. All of them, everybody. There wasn’t a single person I knew or had ever known who wasn’t, in some way, completely full of shit. Why hadn’t I ever seen it?

I squeezed my eyes even tighter and really dug in. “Thrfullashit, thrfullashit, thrfullashit.” I was actually growling, and possibly drooling.

The chant changed again, to screw them all. I didn’t even have to check the list; I just knew it.

“Screwemall, screwemall, screwemall,” I intoned, my voice getting louder as my anger ratcheted up toward rage.

“Screwemall! Screwemall! Screwem…”

“Silence!” the guy at the front bellowed.

It was almost like a physical slap in the face. My eyes popped open.

The man in the robe was no longer alone. Standing next to him was a shorter man in a robe.

“I am Swami Nindak,” he announced with a shy smile.

My insides were still vibrating from all that emotion as I stared at him. My hands were balled into fists, and my stomach wanted to heave. I had no idea why.

He gazed tranquilly about the room, taking in everyone. When he got to me, his eyes seemed to twinkle.

“I see an angry face,” he said in a singsong Indian accent. “That is good. That is very good.”

His gaze moved on until it had covered the entire room. Then he nodded.

“Many of you are familiar with me and my teachings, but some are not, so I will explain: I am not holy and I am not wise. I am merely a vessel, as is every human being. Contained in me, as in all of us, is a potent, universal force: the power of Transcendental Cynicism.”

His fingers were long and delicate. He kept running them through his gray, scraggly beard like a comb, breaking up the tangles. Ordinarily, I would have found this annoying, if not disgusting, but now I found it fascinating.

I glanced around me at the people, noticing their calm, attentive expressions. Had I been the only one with an angry face? And why did he seem to approve of it?

“What is Transcendental Cynicism? It is simply the awareness of fault. There is fault in everything. Perfection does not exist in this world, and seeking it will only end in grief and frustration. The only true path is to recognize that fault exists in everyone and everything. And that it is our duty to find it.”

I’d never heard anything like this, but it resonated with me. All my life I thought I’d been looking for perfection, not settling for the ordinary, following my dreams. But what had it gotten me? A couple of years in a mediocre bar band? A dead-end job in a record store at age twenty-six? A girlfriend I not only did not love, but wasn’t even sure I liked? A girlfriend I couldn’t break up with unless she did it first, over and over?

But maybe my dreams never existed in the first place. Maybe they were just delusions, a colossal waste of time. In that moment it all made perfect sense. My life, as I was living it, was nothing but a colossal waste of time.

“When one discovers fault,” Swami Nindak was saying in his gentle, beguiling voice, “it is not a pleasant experience. It can make one very angry, which is a natural reaction. That is why I am gratified to see angry faces among my followers. It means that they sense the truth, that they understand.”

Boy, did I understand. My fists were still clenched, and I could feel my fingernails digging into my palms.

“But anger is not the goal,” he said. “In fact, it is just the opposite. Anger is the impediment.”

He cocked his head in sly rebuke. I felt immediate, inexplicable shame.

“Anger is what we must transcend. That is why we say our philosophy is ‘transcendental.’ We must surmount our emotions and rise above the dark clouds of anger. We must cut through them, and soar into the clear light of cynicism.”

My eyes filled with tears, because I knew just as sure as I was sitting there that I could never do it. How can anyone recognize that his existence is a meaningless sham and not be wild-eyed, rip-shit furious about it? It seemed impossible.

“It may seem impossible,” Swami Nindak said, freaking me out even more, “but it is not. It is extremely daunting and may take years to accomplish, but it is not impossible. It is a goal we can achieve.

“There is a mantra that can be helpful. It consists of two words: ‘so what?’ Will you join me now in chanting it?”

I tried to clear my mind as I closed my eyes and began chanting “sowat, sowat, sowat” for all I was worth.

It seemed to be working. Yeah, so what? said that inner voice. If it doesn’t really matter, only an idiot would get pissed off about it. It’s not worth your energy.

My anger was diminishing, but it still lurked in the background. It’s the hardest thing in the world to let go of your anger. But it was joined now by a new feeling, a sort of positive fatalism. If it is what it is, then that’s how it is. And so what?

The chant continued for I don’t know how long. Then Swami Nindak said, “Silence.”

He didn’t bellow it like the other guy; he almost whispered it. But it still got through.

I opened my eyes and gazed at his smiling face.

“Do you see?” he asked, looking around the room.

I saw.

“And now,” he continued, “I’m afraid we must end our little gathering for the present. For those who are newcomers, I hope the experience was meaningful and that I will see you again on our next occasion. For those who are acolytes, I hope I have helped to advance your progress in the journey.”

All about me I could sense heads nodding.

“Let us conclude, then, with one final mantra. It is perhaps the most important. That is why you will find it at the very top of your list.”

I did a quick check to see what it was. I hadn’t noticed before, but the words to this one were actually in bold type. It said, “Not necessarily.”

I closed my eyes again and gave myself to it. “Notnecessarily, notnecessarily, notnecessarily.” Of all the chants, this seemed to be the only one whose sounds didn’t mush together when you said them quickly. They sounded clear and like themselves.

“Notnecessarily, notnecessarily, notnecessarily.”

I could have chanted it forever.

~ ~ ~

It was nearly 2 a.m. as I walked in a semi-daze toward the building that housed my shoebox apartment. I was thinking about what I could do with this newfound insight, or even if I could do anything. One thing for sure, I was going back there again the next night.

The only downside of the evening was that Luna and Laal turned out to be an item. I saw them kissing in the vestibule as I was leaving. Oh, well, so what?

As I neared my building, I saw the figure of a woman sitting on the steps in front of the entrance. She was huddled over a book that she was reading by flashlight, and could only be one person. Annabel.

She looked up at me as I approached and gave a soft, embarrassed laugh.

“I haven’t been sitting here the whole time. The coffee shop closed at one, so it’s just been an hour.” She began to cry. “I’m sorry, I’m so, so sorry.”

I took her in my arms and held her.

“It’s okay,” I said. “Come inside.”

I mean, what else could I do?

We got to the apartment and she clung to me. She said she’d been miserable because she understood now how wrong she’d been. How badly she’d treated me.

“I don’t know what I was thinking; it was just stupid politics,” she said, weeping against my shoulder. “You’re wonderful, you’re intelligent, you care for humanity. I love you.”

I held her closer but didn’t say anything in reply. She raised her head and looked into my eyes.

“That’s okay,” she said. “I deserve it.”

She sat down on the bed, which took up most of the space in the apartment, and I made us some coffee on my hot plate.

“How was Frank Zappa?” she asked. “I don’t really hate him. I know he’s a genius. I was just being a bitch.”

“He was amazing,” I said, sitting down next to her and handing her a mug. “But even more amazing was what happened afterward.”

I told her the whole story, minus Luna’s part in it, and her eyes grew big.

“Transcendental Cynicism!” she said in wonder. “I’ve never heard of such a thing.”

“They gave me this pamphlet,” I said, pulling it out of my jeans pocket.

She leafed through it. Annabel is a very quick reader.

“So, there is fault in everyone and everything. Perfection is impossible, and we must find fault. Is that right?”

“Yeah,” I said, “but you make it sound negative. When you chant, you see how positive it is. The experience is electric. It’s coming face-to-face with reality.”

She thought about it for a moment.

“Then there must be something wrong with Transcendental Cynicism, right?”

“I’m not sure I understand,” I said.

“If there’s fault in everything, then there must be fault in Transcendental Cynicism.”

“I…”

She put down her coffee mug and wrapped her arms around me.

“Never mind, don’t listen to me; I was just being terrible again. You had a profound experience. That’s a lot more than I could ever say for myself. You’re an incredible man, and I don’t appreciate you nearly enough. But I’ll try to, Kevin, I swear I will.”

We kissed.

Making love felt as astonishing as ever. As its passion grew I realized how precious she was to me, how lucky I was to have her.

And the intensity I’d felt during those chants was already fading into memory, because she was right. Transcendental Cynicism must have faults, by definition.

“Don’t be fooled, don’t be fooled,” I’d chanted, but maybe one of the things I shouldn’t be fooled by was Transcendental Cynicism.

If there is fault in everyone and everything, and if one of the faults with Transcendental Cynicism is that it doesn’t include a smart, beautiful woman who loves me, then who needs it?

“I love you,” said Annabel, simultaneous with my thought.

“I love you too,” I whispered. And I did, I really did, with every fiber of my being.

We lost ourselves in the sensuous rhythm. Time seemed suspended, which is why I don’t know when it was that I realized what had been going through my head all along, perfectly and relentlessly in sync with our lovemaking.

It was “notnecessarily, notnecessarily, notnecessarily.”