Are You a Good Witch or a Bad Witch?

Robert Wexelblatt

After the tragedy, I tried three times to talk to Betty though what I really longed for was to hug her. I ached to sob with her, to give and take comfort. For thirteen years, we were best friends but she wouldn’t even look at me and, when last I saw her in the garage and ran toward her with my arms open, she stepped back and hissed, “Get off me,” as if I’d actually dared to touch her.

This afternoon, Cecile Glatthorn, assuming I must know or spitefully pointing out that I didn’t, asked me where Betty’s moving. When I said I’d no idea, that I didn’t know she was moving, her eyebrows went up. “Really?” Then she gave her head a sad little shake. “Too many memories of Charlotte, I suppose?”

It seemed to me she made it a question in the hope that I’d admit that Betty was moving to get away from me. I don’t know how much of the story Cecile actually knows. She’s not a bad person, not a terrible gossip, just a woman with a compulsion to know other people’s business. It’s not unlikely that she was jealous of my closeness to Betty, felt shut out, or maybe she just noticed that we stopped seeing each other and wanted to solve the mystery.

So, Betty is moving away. Now she won’t have to squeeze past me in the elevator, run into me in the parking garage. She won’t have to see me anywhere, at any time, ever again.

My big brother dressed up as G. I. Joe when he was about five, then as Superman for three Halloweens in a row. He loved running in his cape, making muscles, narrowing his eyes as he focused his super-vision and super-hearing.

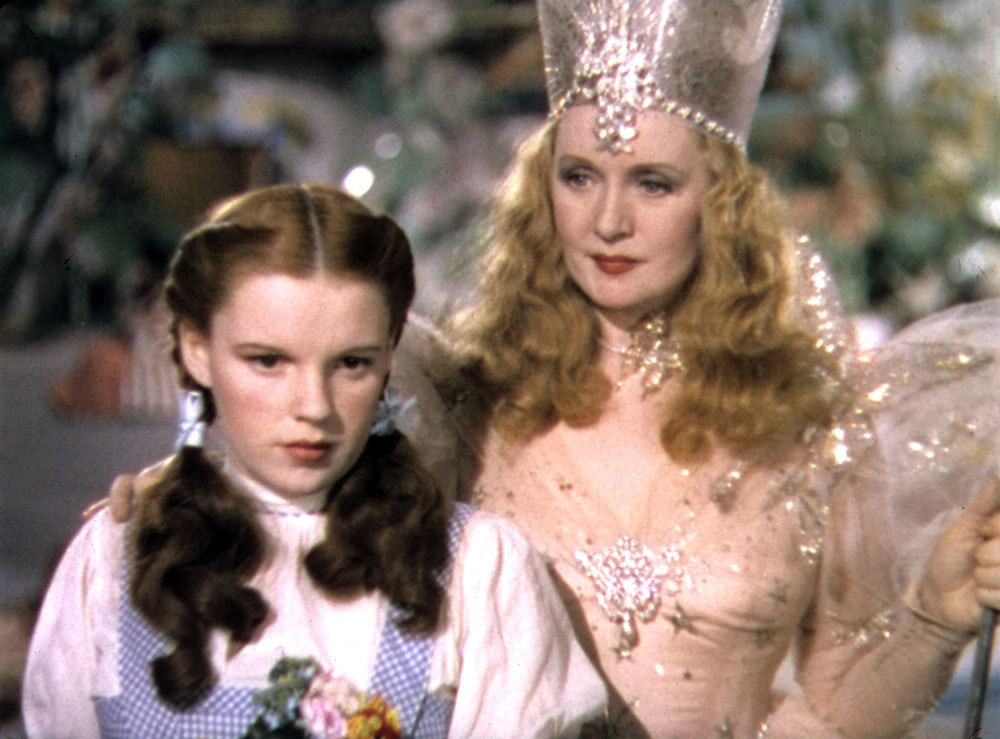

After I saw The Wizard of Oz, I didn’t want to be Dorothy for Halloween; I wanted to be Glinda. My costume turned into a family project. Mother got a length of pink cloth and made a replica of Glinda’s gown with those winged power shoulders. Father strung together chicken wire to hold the skirt out in a full parabola then made a high crown out of cardboard, aluminum foil, and rhinestones left over from the dress. He was so proud of that crown that I think he’d have been glad if I never wore it. As for Joe, he went into the woods and came back with the perfect stick for my wand. He whittled it down, sawed it to length and sanded it smooth. “I want superpowers too, witch powers,” I confided to him, and he said, “Sure. Why not?” As Joe had pretended to see through walls, I pretended I could read people’s minds and look into their future. I boasted to my friends that I could do these things—seriously and not seriously—and they sometimes played along. I remember Marjorie asking if I could change people into animals, “You know, like the way Circe turned men into pigs.” And then Jeannie made us laugh. “Don’t bother,” she said as if she knew more than she probably did. “Boys do that all by themselves.”

It was a game at first, but then I began to semi-believe that I had these powers. I actually did get a sense of what people were thinking; sometimes it was clear but usually muddled. I got a feeling for what lay in store for them too, not anything specific, just whether it would be good or bad, as if life were a trek from one crossroads to the next. Perhaps these “powers” would have gone away if my brother had mocked, if friends hadn’t played along. “What’s Billy Fratangelo thinking about?” or “Should I go to my aunt and uncle’s on Saturday or to the mall with Jeannie?” They were kidding but at the same time they really wanted me to answer. Moreover, I was sometimes right. I’d get these undeniable sensations about what was going to happen—apprehension, excitement, joy, dread. And these feelings, these powers or illusions, didn’t diminish as I got older; I didn’t grow out of them. On the contrary.

I told Joe about my predictions and mind-reading and he didn’t make fun of me even though it was he obvious didn’t believe any of it—or perhaps I should just say Joe believed in my powers even less than I did. I think he didn’t discourage me because he wanted me to give up what might become a delusion on my own. So, every now and then—when we’d be talking about getting into college, some girl he liked, or the rock group I was into—he’d go silent for a moment then suddenly challenge me.

“Okay, tell me what I’m thinking about right now?”

I’d close my eyes and pretend and not pretend to concentrate.

“What every boy your age thinks about at least twenty times an hour,” I said.

“You’re blushing!”

“Am not.”

“Then you’ve just developed one awful rash.”

When Joe was a senior, he asked me about his girlfriend, Brenda, who was a junior.

“Will she dump me when I go away to school?”

I wasn’t in doubt. “Yep. I’d say you can count on it.”

Joe said, “You’re kidding” but he frowned. People are always more likely to believe bad predictions than good ones.

Brenda aside, Joe had a choice to make. He could go to Carnegie-Mellon, the University of Illinois, or West Point. He’d always loved military history. He had the grades for the Academy and he was in great shape, starring on the gymnastics squad for three years. In fact, it was his gym coach, a veteran, who told him he should apply to West Point. They admitted him. G. I. Joe. He suffered through a week of indecision. He listened to our parents go back and forth for days before he turned to me.

“Well, what do you think?”

I said he should go to West Point. I told him I knew he’d have a brilliant military career.

He did go to the Academy and his career was brilliant, for a while. He finished eighth in his class, aced Ranger training, was promoted from second lieutenant to first and then captain in record time. Then, on a night mission in Iraq, my big brother was shot to pieces.

While I’m not puke-green-Margaret-Hamilton ugly, I’m a long way from Melissa Joan Hart and Elizabeth Montgomery. The good looks went to Joe. So, I haven’t lived my life besieged by beaux. In high school, kids traveled in loose clumps more than pairs. This suited me because I could usually secure a place on the periphery of the teenaged scrum. It was almost like belonging. I had plenty of girlfriends to invite me along because I made a good foil; I made the better-looking look better. Then came college.

I chose Champaign-Urbana chiefly because Joe didn’t. Social life was different there, all about pairing-off. The anxious scent of husband-hunting wafted through the women’s dorms; wedlock was romantic culmination to some, market transaction to others—and both at once for those with scope and irony. I had a few dates and only two boyfriends at UI. Gregory Schultz was in my calculus class, at the head of it while I was at the foot. Shy, spectacled, whip-smart, and defensively sarcastic, I thought Gregory’s mind easier to read than Rudin’s Principles of Mathematical Analysis. It seemed to me mostly a jumble of short-lived, incisive perceptions all tangled in a yarn-ball of self-doubt. Two of his thoughts came through vividly on our fifth and last date though, as our clothes were coming off. First, Jesus, what if she gets pregnant? Second, She might be the best I can do.

In a clean anti-mathematical sweep, I dropped Gregory Schultz and Calculus 110 at the same time. For the rest of the semester, Gregory sent me witty and whining emails that all ended with his asking why I broke up with him. That was sophomore year.

The next year I was introduced to Jude Matlaw, an entirely different animal. He was just about perfect and, for some unfathomable reason, seemed to think I was, too. Jude stood six-feet tall, was left-handed, level-headed, modest, wiry, kind, and in his last year. His major was history but he was actually pre-law. He liked fly-fishing, basketball, poetry, the books of Barbara Tuchman and David McCullough, French New Wave cinema, Kansas City barbecue, and me. His mind was lovely to look into, like the paneled reading room at the Library, neat and masculine, polished wood, lots of tall windows and a twenty-foot ceiling. We saw each other from November, when we were introduced at a mixer, through the spring, when he got his acceptance to Columbia Law. We celebrated with a banquet at the Omega Diner and then went for a stroll in the soft air and light of the April evening. We were walking by Boneyard Creek when he suddenly popped the question, sort of.

“Will you wait until I finish law school?”

“For what?”

“To get married, of course.”

I threw my arms around him and said yes, yes, of course.

We had a week together in July. We spent half of it finding him a place to live in Manhattan and the other half in the Quahog Inn on Cape Cod

When school started, Jude set up a schedule. He promised to phone every other night at ten o’clock. During one call, as he was telling me stuff about torts, I got a quick glimpse into his mind, which was usually like a filing cabinet. What I glimpsed was like two snapshots. While listening to him drone on about liability cases, I saw a good-looking redhead with a serious face and smooth hair. She was lifting off her blouse. In the second image, she was naked, belly down, on a bed.

I interrupted Jude’s lecture and asked him if there were any redheads in his Torts class.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” he said quickly, a dead-giveaway that he did.

Then we argued.

Then we broke up.

And that was that. That was really that.

So, I’m single, unwed, and childless, just like that poor old cannibal in her gingerbread house in the forest.

After dropping calculus, I gave up on being pre-med and decided to major in French. I’d liked French in high school, enjoyed books by Gide, Colette, and Duras, adored the movies. My mother and I often watched The French Chef together, did imitations of Julia Child for each other; and, well, the whole idea of Frenchness appealed to me. For the subject of my senior thesis, my tutor suggested Lucie Delarue-Mardus, who wrote far more than I’d preferred, maybe more than she should have.

Impractical degree in hand, I moved to Chicago and found only waitressing jobs. I waited long enough to establish that we weren’t at all suited to one another. Then I had an idea. Flabbergasted that I’d ask after all they’d laid out the four years at UI, my parents nevertheless advanced me the money to enroll in Robert Morris University’s secretarial program, the best in town. I loved it, really took to the work which was exacting yet not demanding. I was sure I’d found my métier, my niche (two fine French words). The orderliness and neatness of the work satisfied me, and the limited demands were soothing. The prospect of serving others with complete emotional detachment was attractive. I even liked my teachers’ trivial hints, like folding any paper you toss away so it’ll take up less space in the wastebasket and never to show up at work bearing cookies. Mastering the latest software made me feel au courant, confident that I’d be worth something on the market.

Electronics Corporation of Chicago, ECC, hired me. I started, of course, at the bottom, in the pool, though they didn’t call it that. When I dared to try them, my powers came in handy. I had a knack, my bosses said, for knowing what they wanted almost before they did. If I saw one of them was about to make a mistake, I learned to give an indirect warning: “Are you sure about that, Mr. Sterling?” I folded what I didn’t shred, never brought cookies, and moved up quickly, rank after rank, just as Joe had. When the CEO’s longtime executive assistant retired, HR sent me to be interviewed. I had a good feeling about how it would go and I got the job. Before long, Mr. Barthelemy was introducing me as “the pin in the pinwheel,” as if he hadn’t just hired but invented me. Praises and raises have not been lacking. “I don’t want to lose you,” he said when giving me a big increase. “It’s as if you can read my mind.”

I saved up, paid my parents back, and made the down payment on my big two-bedroom condo on North Wells Street. I moved in three months before newly-divorced Betty and seven-year-old Charlotte moved in one floor up. Betty was an anesthesiologist; Charlotte was adorable. That first night I brought them a brisket with bliss potatoes, parsnips, carrots, and green beans.

Betty had more of a social life than I did—who didn’t? Also, she was sometimes called to the hospital for emergencies. One night, desperate because her regular sitter wasn’t available, she phoned to ask if I could possibly stay with Charlotte. She thought it might be for a couple of hours, maybe three.

I brought up the makings for macaroni and cheese and my DVD of The Wizard of Oz. Charlotte was easy to love. There was nothing mean about her, nothing but sweetness and worries that did her credit and which I liked relieving. Over time, as Scrooge was to Tiny Tim, I thought of myself as a second mother to Charlotte. She popped in to my place whenever she liked, for talks and treats. We binged together on Disney movies. I taught her some French--nous sommes les meilleurs amis, n’est-ce pas?--and, when she had to pick a foreign language in middle school, she chose French, naturellement. I gave her two books by Colette for her fourteenth birthday. We watched films by Truffaut and Godard. Charlotte told me things she said she couldn’t tell her mother and I never once betrayed her confidence. She worried about Betty being lonely and she missed her father; later, it was her grades, hair, thighs, and boys. Lots of boys were interested in Charlotte. And so it went for a decade.

Betty was forlorn when Charlotte went off to Tufts. For three days she went sort of mad. I wasn’t much better, to tell the truth. Betty and I talked every night and maybe that helped us, the consolation of feeling the same things.

Charlotte phoned home regularly and wrote me weekly emails, some of them quite long. Betty got the big picture; I got the details. In one email, Charlotte said she was feeling depressed and didn’t know why, since things were actually going very well. I phoned her because I thought if I could hear her voice I might be able to see into her mind. And it was true—at least I thought it was. She was just blue; it wasn’t anything serious. Anxiety, self-criticism, a little homesickness, feeling like the East wasn’t for her. I told her a French joke and was pleased to hear her giggle.

Though I never shared with Betty all I knew about Charlotte, I did tell her everything about myself. She was my one confidante, what my brother once was, might have been. She knew about Joe and about Jude. I even told her about my “powers,” which amused her. She didn’t ridicule me but she was, after all, an unmetaphysical physician. When I beat her at gin rummy or Scrabble she’d tease me about reading her mind.

Charlotte had a string of boyfriends during her first two years at Tufts, none really serious. But in her junior year, she fell in love. His name was Geoffrey Longacre, an economics major from Westchester county, from money. He took her on expensive dates in Boston. I learned a lot from her emails about Beantown gastronomy, concerts, and theater. For Thanksgiving, she went to Westchester. The visit went well. Geoffrey’s family welcomed her warmly, and their two golden retrievers would hardly leave her side.

Betty went to Boston for a weekend early in December to meet Geoffrey. She was favorably impressed, took lots of pictures, and gave me a complete rundown when she got back. Geoffrey was handsome, polite, and obviously—Betty said “spectacularly”—enamored of Charlotte. All good.

I met Geoffrey when he and Charlotte came to Chicago for Christmas. I was invited to dinner on Christmas Eve. I was uneasy from the first. It wasn’t that I didn’t like the young man or that I found anything disturbing about him, in his mind—nothing beyond some understandably risqué images of Charlotte. It was a feeling about the future that shook me. It wasn’t specific but it was definitely bad. Something terrible would happen if the couple married; that’s what I felt. I did my best to dismiss my uneasiness and couldn’t. It kept me up that night and was even worse when I went upstairs with my presents the next day. I told myself that I was wrong, denied my “powers,” chided myself for indulging a delusion. But the dread only deepened.

I knew I was on thin ice and told myself to keep my mouth shut, that it wasn’t really any of my business. Anyway, what could I say that wouldn’t be dismissed and resented? I was in anguish but also perplexed. Geoffrey Longacre was a fine fellow; he and Charlotte were in love, talented, could look forward to a happy future. Though I knew Betty thought her daughter too young to marry she didn’t make an issue of it. My dread was a certainty wrapped up in uncertainty. I looked at the couple and was filled with inexplicable horror.

In the end, I had to tell Betty, to warn her.

“What are you talking about?”

“I don’t know what, not exactly. I just feel it.”

Betty grew angry, then furious. “It’s that crazy fantasy of yours. The witch business, isn’t it?” she scoffed.

“What can I do? You’ve got to believe me.”

It was terrible, Betty’s face, what she said.

“Believe you? Believe in a neurotic delusion you’ve been cultivating your whole life? Believe in some hallucinations that make you feel better about yourself, that you’re special?” She looked at me with disgust, without pity. “Don’t you see what’s going on here?”

“What do you mean?”

Then it poured out.

“Joe and Jude. Especially Jude. You’re jealous of Charlotte. She’s got what you threw away. And not only that. You’ve always been jealous of me because of Charlotte. Admit it. You’ve wanted to take her from me with your little confidences. I know all about them. I indulged you and so did Charlotte. We’d laugh about it. But this is too pathetic. You’re pathetic. The bad fairy at the feast.”

“No, no. Don’t say that. It’s what I feel. I can’t explain.”

“Don’t bother trying. Just leave.”

I wasn’t invited to the wedding. Charlotte, informed by Betty, didn’t reply to my emails. I was now the bad fairy, the wicked, envious, lonely, barren witch.

Horribly ironic that Betty, so level-headed, so grounded, so sensibly dismissive of my “powers,” should hold me responsible for what happened, as if it were my doing, the fulfilment of a spiteful wish.

The couple honeymooned in the Bahamas. I only found out where they’d gone when the tragedy hit the news. Betty didn’t tell me, didn’t come to weep with me. I saw the story on television. Charlotte and Geoffrey—a vibrant, joyful wedding picture on the TV—drowned while skin-diving.

What was it? Bad scuba gear? Some sex thing? Rapture of the deep? The authorities, said the announcer, were investigating.

And what was I? And who would investigate me?

Robert Wexelblatt

After the tragedy, I tried three times to talk to Betty though what I really longed for was to hug her. I ached to sob with her, to give and take comfort. For thirteen years, we were best friends but she wouldn’t even look at me and, when last I saw her in the garage and ran toward her with my arms open, she stepped back and hissed, “Get off me,” as if I’d actually dared to touch her.

This afternoon, Cecile Glatthorn, assuming I must know or spitefully pointing out that I didn’t, asked me where Betty’s moving. When I said I’d no idea, that I didn’t know she was moving, her eyebrows went up. “Really?” Then she gave her head a sad little shake. “Too many memories of Charlotte, I suppose?”

It seemed to me she made it a question in the hope that I’d admit that Betty was moving to get away from me. I don’t know how much of the story Cecile actually knows. She’s not a bad person, not a terrible gossip, just a woman with a compulsion to know other people’s business. It’s not unlikely that she was jealous of my closeness to Betty, felt shut out, or maybe she just noticed that we stopped seeing each other and wanted to solve the mystery.

So, Betty is moving away. Now she won’t have to squeeze past me in the elevator, run into me in the parking garage. She won’t have to see me anywhere, at any time, ever again.

My big brother dressed up as G. I. Joe when he was about five, then as Superman for three Halloweens in a row. He loved running in his cape, making muscles, narrowing his eyes as he focused his super-vision and super-hearing.

After I saw The Wizard of Oz, I didn’t want to be Dorothy for Halloween; I wanted to be Glinda. My costume turned into a family project. Mother got a length of pink cloth and made a replica of Glinda’s gown with those winged power shoulders. Father strung together chicken wire to hold the skirt out in a full parabola then made a high crown out of cardboard, aluminum foil, and rhinestones left over from the dress. He was so proud of that crown that I think he’d have been glad if I never wore it. As for Joe, he went into the woods and came back with the perfect stick for my wand. He whittled it down, sawed it to length and sanded it smooth. “I want superpowers too, witch powers,” I confided to him, and he said, “Sure. Why not?” As Joe had pretended to see through walls, I pretended I could read people’s minds and look into their future. I boasted to my friends that I could do these things—seriously and not seriously—and they sometimes played along. I remember Marjorie asking if I could change people into animals, “You know, like the way Circe turned men into pigs.” And then Jeannie made us laugh. “Don’t bother,” she said as if she knew more than she probably did. “Boys do that all by themselves.”

It was a game at first, but then I began to semi-believe that I had these powers. I actually did get a sense of what people were thinking; sometimes it was clear but usually muddled. I got a feeling for what lay in store for them too, not anything specific, just whether it would be good or bad, as if life were a trek from one crossroads to the next. Perhaps these “powers” would have gone away if my brother had mocked, if friends hadn’t played along. “What’s Billy Fratangelo thinking about?” or “Should I go to my aunt and uncle’s on Saturday or to the mall with Jeannie?” They were kidding but at the same time they really wanted me to answer. Moreover, I was sometimes right. I’d get these undeniable sensations about what was going to happen—apprehension, excitement, joy, dread. And these feelings, these powers or illusions, didn’t diminish as I got older; I didn’t grow out of them. On the contrary.

I told Joe about my predictions and mind-reading and he didn’t make fun of me even though it was he obvious didn’t believe any of it—or perhaps I should just say Joe believed in my powers even less than I did. I think he didn’t discourage me because he wanted me to give up what might become a delusion on my own. So, every now and then—when we’d be talking about getting into college, some girl he liked, or the rock group I was into—he’d go silent for a moment then suddenly challenge me.

“Okay, tell me what I’m thinking about right now?”

I’d close my eyes and pretend and not pretend to concentrate.

“What every boy your age thinks about at least twenty times an hour,” I said.

“You’re blushing!”

“Am not.”

“Then you’ve just developed one awful rash.”

When Joe was a senior, he asked me about his girlfriend, Brenda, who was a junior.

“Will she dump me when I go away to school?”

I wasn’t in doubt. “Yep. I’d say you can count on it.”

Joe said, “You’re kidding” but he frowned. People are always more likely to believe bad predictions than good ones.

Brenda aside, Joe had a choice to make. He could go to Carnegie-Mellon, the University of Illinois, or West Point. He’d always loved military history. He had the grades for the Academy and he was in great shape, starring on the gymnastics squad for three years. In fact, it was his gym coach, a veteran, who told him he should apply to West Point. They admitted him. G. I. Joe. He suffered through a week of indecision. He listened to our parents go back and forth for days before he turned to me.

“Well, what do you think?”

I said he should go to West Point. I told him I knew he’d have a brilliant military career.

He did go to the Academy and his career was brilliant, for a while. He finished eighth in his class, aced Ranger training, was promoted from second lieutenant to first and then captain in record time. Then, on a night mission in Iraq, my big brother was shot to pieces.

While I’m not puke-green-Margaret-Hamilton ugly, I’m a long way from Melissa Joan Hart and Elizabeth Montgomery. The good looks went to Joe. So, I haven’t lived my life besieged by beaux. In high school, kids traveled in loose clumps more than pairs. This suited me because I could usually secure a place on the periphery of the teenaged scrum. It was almost like belonging. I had plenty of girlfriends to invite me along because I made a good foil; I made the better-looking look better. Then came college.

I chose Champaign-Urbana chiefly because Joe didn’t. Social life was different there, all about pairing-off. The anxious scent of husband-hunting wafted through the women’s dorms; wedlock was romantic culmination to some, market transaction to others—and both at once for those with scope and irony. I had a few dates and only two boyfriends at UI. Gregory Schultz was in my calculus class, at the head of it while I was at the foot. Shy, spectacled, whip-smart, and defensively sarcastic, I thought Gregory’s mind easier to read than Rudin’s Principles of Mathematical Analysis. It seemed to me mostly a jumble of short-lived, incisive perceptions all tangled in a yarn-ball of self-doubt. Two of his thoughts came through vividly on our fifth and last date though, as our clothes were coming off. First, Jesus, what if she gets pregnant? Second, She might be the best I can do.

In a clean anti-mathematical sweep, I dropped Gregory Schultz and Calculus 110 at the same time. For the rest of the semester, Gregory sent me witty and whining emails that all ended with his asking why I broke up with him. That was sophomore year.

The next year I was introduced to Jude Matlaw, an entirely different animal. He was just about perfect and, for some unfathomable reason, seemed to think I was, too. Jude stood six-feet tall, was left-handed, level-headed, modest, wiry, kind, and in his last year. His major was history but he was actually pre-law. He liked fly-fishing, basketball, poetry, the books of Barbara Tuchman and David McCullough, French New Wave cinema, Kansas City barbecue, and me. His mind was lovely to look into, like the paneled reading room at the Library, neat and masculine, polished wood, lots of tall windows and a twenty-foot ceiling. We saw each other from November, when we were introduced at a mixer, through the spring, when he got his acceptance to Columbia Law. We celebrated with a banquet at the Omega Diner and then went for a stroll in the soft air and light of the April evening. We were walking by Boneyard Creek when he suddenly popped the question, sort of.

“Will you wait until I finish law school?”

“For what?”

“To get married, of course.”

I threw my arms around him and said yes, yes, of course.

We had a week together in July. We spent half of it finding him a place to live in Manhattan and the other half in the Quahog Inn on Cape Cod

When school started, Jude set up a schedule. He promised to phone every other night at ten o’clock. During one call, as he was telling me stuff about torts, I got a quick glimpse into his mind, which was usually like a filing cabinet. What I glimpsed was like two snapshots. While listening to him drone on about liability cases, I saw a good-looking redhead with a serious face and smooth hair. She was lifting off her blouse. In the second image, she was naked, belly down, on a bed.

I interrupted Jude’s lecture and asked him if there were any redheads in his Torts class.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” he said quickly, a dead-giveaway that he did.

Then we argued.

Then we broke up.

And that was that. That was really that.

So, I’m single, unwed, and childless, just like that poor old cannibal in her gingerbread house in the forest.

After dropping calculus, I gave up on being pre-med and decided to major in French. I’d liked French in high school, enjoyed books by Gide, Colette, and Duras, adored the movies. My mother and I often watched The French Chef together, did imitations of Julia Child for each other; and, well, the whole idea of Frenchness appealed to me. For the subject of my senior thesis, my tutor suggested Lucie Delarue-Mardus, who wrote far more than I’d preferred, maybe more than she should have.

Impractical degree in hand, I moved to Chicago and found only waitressing jobs. I waited long enough to establish that we weren’t at all suited to one another. Then I had an idea. Flabbergasted that I’d ask after all they’d laid out the four years at UI, my parents nevertheless advanced me the money to enroll in Robert Morris University’s secretarial program, the best in town. I loved it, really took to the work which was exacting yet not demanding. I was sure I’d found my métier, my niche (two fine French words). The orderliness and neatness of the work satisfied me, and the limited demands were soothing. The prospect of serving others with complete emotional detachment was attractive. I even liked my teachers’ trivial hints, like folding any paper you toss away so it’ll take up less space in the wastebasket and never to show up at work bearing cookies. Mastering the latest software made me feel au courant, confident that I’d be worth something on the market.

Electronics Corporation of Chicago, ECC, hired me. I started, of course, at the bottom, in the pool, though they didn’t call it that. When I dared to try them, my powers came in handy. I had a knack, my bosses said, for knowing what they wanted almost before they did. If I saw one of them was about to make a mistake, I learned to give an indirect warning: “Are you sure about that, Mr. Sterling?” I folded what I didn’t shred, never brought cookies, and moved up quickly, rank after rank, just as Joe had. When the CEO’s longtime executive assistant retired, HR sent me to be interviewed. I had a good feeling about how it would go and I got the job. Before long, Mr. Barthelemy was introducing me as “the pin in the pinwheel,” as if he hadn’t just hired but invented me. Praises and raises have not been lacking. “I don’t want to lose you,” he said when giving me a big increase. “It’s as if you can read my mind.”

I saved up, paid my parents back, and made the down payment on my big two-bedroom condo on North Wells Street. I moved in three months before newly-divorced Betty and seven-year-old Charlotte moved in one floor up. Betty was an anesthesiologist; Charlotte was adorable. That first night I brought them a brisket with bliss potatoes, parsnips, carrots, and green beans.

Betty had more of a social life than I did—who didn’t? Also, she was sometimes called to the hospital for emergencies. One night, desperate because her regular sitter wasn’t available, she phoned to ask if I could possibly stay with Charlotte. She thought it might be for a couple of hours, maybe three.

I brought up the makings for macaroni and cheese and my DVD of The Wizard of Oz. Charlotte was easy to love. There was nothing mean about her, nothing but sweetness and worries that did her credit and which I liked relieving. Over time, as Scrooge was to Tiny Tim, I thought of myself as a second mother to Charlotte. She popped in to my place whenever she liked, for talks and treats. We binged together on Disney movies. I taught her some French--nous sommes les meilleurs amis, n’est-ce pas?--and, when she had to pick a foreign language in middle school, she chose French, naturellement. I gave her two books by Colette for her fourteenth birthday. We watched films by Truffaut and Godard. Charlotte told me things she said she couldn’t tell her mother and I never once betrayed her confidence. She worried about Betty being lonely and she missed her father; later, it was her grades, hair, thighs, and boys. Lots of boys were interested in Charlotte. And so it went for a decade.

Betty was forlorn when Charlotte went off to Tufts. For three days she went sort of mad. I wasn’t much better, to tell the truth. Betty and I talked every night and maybe that helped us, the consolation of feeling the same things.

Charlotte phoned home regularly and wrote me weekly emails, some of them quite long. Betty got the big picture; I got the details. In one email, Charlotte said she was feeling depressed and didn’t know why, since things were actually going very well. I phoned her because I thought if I could hear her voice I might be able to see into her mind. And it was true—at least I thought it was. She was just blue; it wasn’t anything serious. Anxiety, self-criticism, a little homesickness, feeling like the East wasn’t for her. I told her a French joke and was pleased to hear her giggle.

Though I never shared with Betty all I knew about Charlotte, I did tell her everything about myself. She was my one confidante, what my brother once was, might have been. She knew about Joe and about Jude. I even told her about my “powers,” which amused her. She didn’t ridicule me but she was, after all, an unmetaphysical physician. When I beat her at gin rummy or Scrabble she’d tease me about reading her mind.

Charlotte had a string of boyfriends during her first two years at Tufts, none really serious. But in her junior year, she fell in love. His name was Geoffrey Longacre, an economics major from Westchester county, from money. He took her on expensive dates in Boston. I learned a lot from her emails about Beantown gastronomy, concerts, and theater. For Thanksgiving, she went to Westchester. The visit went well. Geoffrey’s family welcomed her warmly, and their two golden retrievers would hardly leave her side.

Betty went to Boston for a weekend early in December to meet Geoffrey. She was favorably impressed, took lots of pictures, and gave me a complete rundown when she got back. Geoffrey was handsome, polite, and obviously—Betty said “spectacularly”—enamored of Charlotte. All good.

I met Geoffrey when he and Charlotte came to Chicago for Christmas. I was invited to dinner on Christmas Eve. I was uneasy from the first. It wasn’t that I didn’t like the young man or that I found anything disturbing about him, in his mind—nothing beyond some understandably risqué images of Charlotte. It was a feeling about the future that shook me. It wasn’t specific but it was definitely bad. Something terrible would happen if the couple married; that’s what I felt. I did my best to dismiss my uneasiness and couldn’t. It kept me up that night and was even worse when I went upstairs with my presents the next day. I told myself that I was wrong, denied my “powers,” chided myself for indulging a delusion. But the dread only deepened.

I knew I was on thin ice and told myself to keep my mouth shut, that it wasn’t really any of my business. Anyway, what could I say that wouldn’t be dismissed and resented? I was in anguish but also perplexed. Geoffrey Longacre was a fine fellow; he and Charlotte were in love, talented, could look forward to a happy future. Though I knew Betty thought her daughter too young to marry she didn’t make an issue of it. My dread was a certainty wrapped up in uncertainty. I looked at the couple and was filled with inexplicable horror.

In the end, I had to tell Betty, to warn her.

“What are you talking about?”

“I don’t know what, not exactly. I just feel it.”

Betty grew angry, then furious. “It’s that crazy fantasy of yours. The witch business, isn’t it?” she scoffed.

“What can I do? You’ve got to believe me.”

It was terrible, Betty’s face, what she said.

“Believe you? Believe in a neurotic delusion you’ve been cultivating your whole life? Believe in some hallucinations that make you feel better about yourself, that you’re special?” She looked at me with disgust, without pity. “Don’t you see what’s going on here?”

“What do you mean?”

Then it poured out.

“Joe and Jude. Especially Jude. You’re jealous of Charlotte. She’s got what you threw away. And not only that. You’ve always been jealous of me because of Charlotte. Admit it. You’ve wanted to take her from me with your little confidences. I know all about them. I indulged you and so did Charlotte. We’d laugh about it. But this is too pathetic. You’re pathetic. The bad fairy at the feast.”

“No, no. Don’t say that. It’s what I feel. I can’t explain.”

“Don’t bother trying. Just leave.”

I wasn’t invited to the wedding. Charlotte, informed by Betty, didn’t reply to my emails. I was now the bad fairy, the wicked, envious, lonely, barren witch.

Horribly ironic that Betty, so level-headed, so grounded, so sensibly dismissive of my “powers,” should hold me responsible for what happened, as if it were my doing, the fulfilment of a spiteful wish.

The couple honeymooned in the Bahamas. I only found out where they’d gone when the tragedy hit the news. Betty didn’t tell me, didn’t come to weep with me. I saw the story on television. Charlotte and Geoffrey—a vibrant, joyful wedding picture on the TV—drowned while skin-diving.

What was it? Bad scuba gear? Some sex thing? Rapture of the deep? The authorities, said the announcer, were investigating.

And what was I? And who would investigate me?