The New Math

Jerry Jerman

Ray squirms over the open pages of his math book and tries for the millionth time to figure it out. The letters he understands, the numbers he understands, but the combination just doesn’t make sense. If he had Superman’s laser vision, he’d incinerate these meaningless pages. But unfortunately, no fire. Of course, no Superman either. And who can concentrate on this ugly, scratchy sofa? His sister’s got the radio blaring in her room. His mother’s rattling pans in the kitchen. From somewhere outside: an abrupt boom. Concentrate, he tells himself, his eyes still on the page. All that matters are these stupid X’s and Y’s.

He’s going to figure it out if it kills him.

Seventh grade is starting out to be a real bitch.

After a long while a clock chimes in another room, once. Four-thirty already? He hears the whine of a siren and slaps his palms against his ears. Stop! Now his ears hurt and his homework isn’t getting done. And he’s hungry.

These distractions aren’t helping.

Time drags and his mother sweeps past, her sudden presence diverting him yet again. His surroundings snap to life. The hard, brown sofa. The worn green carpet. The ugly painting on the living room wall. And the doorbell: when did that ring?

Their neighbor, Mrs. Dunlap, pushes past his mother into the living room.

She says, breathless, “Did you hear?”

Mrs. Dunlap whispers but he can hear her. A man down the street just killed himself, she says. Not thirty minutes ago.

“You must’ve heard it,” Mrs. Dunlap says. “That loud boom?”

“I thought I heard a car backfire.”

“That was a shotgun.”

Ray looks up. As the women go out on the front porch, he hears Mrs. Dunlap say, “That poor Lily. She and Jenny discovered the body.”

The name Jenny rouses him even more and he follows them outside, still clutching the math book. Along the block clumps of people stand on their lawns looking toward a stone house down the street. Jenny’s house. A police car is parked in the driveway, its flashing lights sweeping across the grass, the house, the sidewalk. Much later, a gray hearse pulls into the driveway. Mrs. Dunlap leaves and his mother goes back inside the house. He watches for a while and then sits on the cold porch steps and flips through the math book again.

It still doesn’t make any sense.

~ ~ ~

Jenny Tyler is his girlfriend, though not really. No jewelry, no dates, no kissing. Besides, what twelve-year-old has a real girlfriend? He didn’t know what to make of it, not really. He wasn’t even sure what attracted him to Jenny in the first place. Once that summer they’d gone with her family to see some cartoon with dinosaurs. The movie sucked but he got to sit beside Jenny the whole time, their elbows touching, almost like boyfriend-girlfriend, a vaguely electric stirring of something inside him. Really though it’s just a dumb sixth grade idea that has spilled over into the seventh.

~ ~ ~

He returns to the math book page full of X’s and Y’s and rereads the boring explanation and tries to remember what the teacher had said that day. Other kids in class hadn’t acted confused, so he begins to think it’s him. Some kids just get things, others don’t. Isn’t that it? For a moment he worries that he’s going to be one of the ones who don’t.

He slams the book shut and with his finger traces an X on the back cover. The thing is he keeps seeing Mr. Tyler’s face gazing back at him, his dark eyes shining. He liked Mr. Tyler who used to talk to him when he came over to visit Jenny. He imagines the man in his living room. Sees him aim the barrel of a shotgun beneath his chin and then, without hesitating, squeeze the trigger. His head bursts apart like an exploded firecracker. He falls spread-eagled on the floor, another X. Ray shoves the book away. He imagines that instant where one second you’re looking at things in a room and then there’s nothing but black, like snapping off a light: a sudden darkness. Mr. Tyler seemed happy enough—what made him do it? For a moment he shuts his eyes and tries to imagine being dead, but he hears a dog bark and a kid yell and a car go by, feels a faint warm breeze, and figures that’s nothing like death.

When he opens his eyes, he sees Jenny down the street, her bright red hair a small flaming torch in the dull yellow afternoon. She and her mother huddle together and a man he doesn’t know guides them toward a car. They get in and the man drives them away.

~ ~ ~

The sun bleeds above the horizon and Ray watches a car pull into the driveway. His father gets out and smiles and waves but is quickly distracted by the activity down the street. He hurries into the side door of the house.

A long time later Ray’s mother leans out the front door and says dinner’s almost ready. He continues watching the stone house. Finally, two men in black overalls and black gloves come out, rolling a gurney between them. There’s a long gray bag on the gurney. They put the bag into the hearse and drive off.

Ray gets up and goes inside. At dinner no one says anything about what had happened down the street. His dad asks about his homework. Ray tries to describe his problems with math.

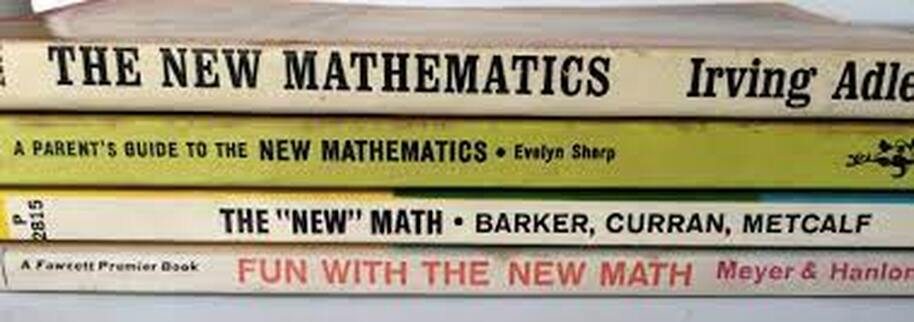

His father looks at his mother and says, “Isn’t that what they called the new math when we were Ray’s age?”

“I think so,” his mother says.

Ray looks at them and thinks, new math? No way. This has been going on a long time.

Jerry Jerman

Ray squirms over the open pages of his math book and tries for the millionth time to figure it out. The letters he understands, the numbers he understands, but the combination just doesn’t make sense. If he had Superman’s laser vision, he’d incinerate these meaningless pages. But unfortunately, no fire. Of course, no Superman either. And who can concentrate on this ugly, scratchy sofa? His sister’s got the radio blaring in her room. His mother’s rattling pans in the kitchen. From somewhere outside: an abrupt boom. Concentrate, he tells himself, his eyes still on the page. All that matters are these stupid X’s and Y’s.

He’s going to figure it out if it kills him.

Seventh grade is starting out to be a real bitch.

After a long while a clock chimes in another room, once. Four-thirty already? He hears the whine of a siren and slaps his palms against his ears. Stop! Now his ears hurt and his homework isn’t getting done. And he’s hungry.

These distractions aren’t helping.

Time drags and his mother sweeps past, her sudden presence diverting him yet again. His surroundings snap to life. The hard, brown sofa. The worn green carpet. The ugly painting on the living room wall. And the doorbell: when did that ring?

Their neighbor, Mrs. Dunlap, pushes past his mother into the living room.

She says, breathless, “Did you hear?”

Mrs. Dunlap whispers but he can hear her. A man down the street just killed himself, she says. Not thirty minutes ago.

“You must’ve heard it,” Mrs. Dunlap says. “That loud boom?”

“I thought I heard a car backfire.”

“That was a shotgun.”

Ray looks up. As the women go out on the front porch, he hears Mrs. Dunlap say, “That poor Lily. She and Jenny discovered the body.”

The name Jenny rouses him even more and he follows them outside, still clutching the math book. Along the block clumps of people stand on their lawns looking toward a stone house down the street. Jenny’s house. A police car is parked in the driveway, its flashing lights sweeping across the grass, the house, the sidewalk. Much later, a gray hearse pulls into the driveway. Mrs. Dunlap leaves and his mother goes back inside the house. He watches for a while and then sits on the cold porch steps and flips through the math book again.

It still doesn’t make any sense.

~ ~ ~

Jenny Tyler is his girlfriend, though not really. No jewelry, no dates, no kissing. Besides, what twelve-year-old has a real girlfriend? He didn’t know what to make of it, not really. He wasn’t even sure what attracted him to Jenny in the first place. Once that summer they’d gone with her family to see some cartoon with dinosaurs. The movie sucked but he got to sit beside Jenny the whole time, their elbows touching, almost like boyfriend-girlfriend, a vaguely electric stirring of something inside him. Really though it’s just a dumb sixth grade idea that has spilled over into the seventh.

~ ~ ~

He returns to the math book page full of X’s and Y’s and rereads the boring explanation and tries to remember what the teacher had said that day. Other kids in class hadn’t acted confused, so he begins to think it’s him. Some kids just get things, others don’t. Isn’t that it? For a moment he worries that he’s going to be one of the ones who don’t.

He slams the book shut and with his finger traces an X on the back cover. The thing is he keeps seeing Mr. Tyler’s face gazing back at him, his dark eyes shining. He liked Mr. Tyler who used to talk to him when he came over to visit Jenny. He imagines the man in his living room. Sees him aim the barrel of a shotgun beneath his chin and then, without hesitating, squeeze the trigger. His head bursts apart like an exploded firecracker. He falls spread-eagled on the floor, another X. Ray shoves the book away. He imagines that instant where one second you’re looking at things in a room and then there’s nothing but black, like snapping off a light: a sudden darkness. Mr. Tyler seemed happy enough—what made him do it? For a moment he shuts his eyes and tries to imagine being dead, but he hears a dog bark and a kid yell and a car go by, feels a faint warm breeze, and figures that’s nothing like death.

When he opens his eyes, he sees Jenny down the street, her bright red hair a small flaming torch in the dull yellow afternoon. She and her mother huddle together and a man he doesn’t know guides them toward a car. They get in and the man drives them away.

~ ~ ~

The sun bleeds above the horizon and Ray watches a car pull into the driveway. His father gets out and smiles and waves but is quickly distracted by the activity down the street. He hurries into the side door of the house.

A long time later Ray’s mother leans out the front door and says dinner’s almost ready. He continues watching the stone house. Finally, two men in black overalls and black gloves come out, rolling a gurney between them. There’s a long gray bag on the gurney. They put the bag into the hearse and drive off.

Ray gets up and goes inside. At dinner no one says anything about what had happened down the street. His dad asks about his homework. Ray tries to describe his problems with math.

His father looks at his mother and says, “Isn’t that what they called the new math when we were Ray’s age?”

“I think so,” his mother says.

Ray looks at them and thinks, new math? No way. This has been going on a long time.