Fast Trains

Gary V. Powell

_ When Brad Phillips was a kid, getting from one side of town to the other had been damn near impossible, what with the trains running day and night across the Indiana countryside, New York to Chicago. To make it easier they put in the Third Street underpass, the Highway 19 bypass, and more recently, the US 20 overpass. Miles Labs and Conn Instruments were still in town in those days; RVs were booming. Then this latest recession hit, the Great Recession the TV news called it. The drug companies cleared out, the RV factories closed, and the trains stopped running, except for the morning and evening Norfolk Southern freight and the Amtrak that blew through once a day.

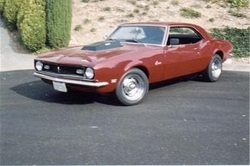

Brad lit a cigarette, sat on the hood of his cherry red’68 Camaro, and waited for the morning freight, a double-stacked car carrier, to pass. Halfway between Elkhart and Goshen this was one of the last remaining crossings without gates; only a standard crossbuck marked the tracks. In years past there had been accidents here followed by talk of gates and better lighting, but with train traffic down and money short, the talk had stopped. When both Brad and the Camaro had been younger, they’d played a game, racing trains along the county road running parallel to the tracks, then cutting in front at the crossing, seeing how close they could pass to that sick grind of steel on steel.

You know, just for the hell of it.

Winter was coming on. He could feel it in the cold, damp air, see it in the white-gray sky that would remain mostly the same until spring. In years past, winter had meant shoveling out and rigging chains on tires just so a man could get through. This year, it meant mounting heat bills and cabin fever. Before long, his unemployment would run out, and he wasn’t sure what that meant. He hunched his shoulders and sunk a little deeper into his old Pea coat.

The Camaro was the last thing left to sell. His ex-wife had taken the furniture, the TV, and his bass boat. All he’d wanted after thirty years was that cherry red Camaro.

* * *

The Waterfall diner near the Johnson Street dam was as full as it would have been for breakfast in the old days, except this wasn’t breakfast time. This was ten o’clock in the morning, and these weren’t men on their way to work. These were men laid off, caught up in a wave they hadn’t seen coming and couldn’t outrun. Brad scooched in next to his oldest boy, Lee, across from Randy Miller and Zeke Cramer. He’d worked with Randy and Zeke at the Nomad plant, Randy in cabinets and Zeke in sidewall, from the plant’s start-up in the ’80s until it’s closing a few months earlier. Lee had stayed on at the lumber yard until the week before.

In his early thirties, with a wife and two kids of his own, Lee spoke to his old man from behind a cup of coffee. “So, did you do, it?”

Brad nodded. He was a big man, six-two and two-fifty, with calloused hands, muscular shoulders and arms, and a thick chest. He’d been Nomad’s roofer, assembling and setting twenty, twenty-five roofs a day, when business was good. “Yeah, I did it.”

Lee turned away and stared out the window.

Zeke dug inside his ear. “Zowee,” he said. A fat man with a weak chin, he was getting fatter by the minute now that he had more time to devote to his eating. He wore overhauls tucked inside his yellow boots, the kind firemen wore.

Randy, tall and lean, with a graying handle-bar mustache, spoke in a deep bass voice. “So, how much did you get?”

Brad reached into his pocket and brought forth a roll of cash bound by a rubber band. He set it on the table. “Forty thou, give or take a little. It’s down to thirty-five now. I bought a piece-of-shit pick-up to get around in at Yoder’s Ford.”

Randy shook a cigarette out of his pack, then tucked it behind his ear. Smoking was no longer allowed at the Waterfall. “That cherry red Camaro. The first time we got laid was in that Camaro.”

Lee grinned. “Come on, you got laid?”

“Once, smart-ass,” Randy said.

Brad ignored the BS, Randy and Lee always going after each other, and retrieved his roll of cash. “Anyway, it’s done.”

Zeke stood and pulled his Harley Motorcycle cap down on his forehead. “I gotta see a man about some firewood.”

“Maybe you should move south,” Randy said. “Somewhere you don’t have to pay for heat.”

“I was thinking of wintering in Tahiti, myself,” Lee said. “I hear the women go topless there.”

Zeke dropped three dollars on the table to cover his coffee. “You can get that down at Night Moves.”

“Not for free, though.” Randy and Lee had it in unison.

Brad shoved the three bills back in Zeke’s direction. “This one’s on me.”

Zeke winced, but retrieved his money. “Thanks, Brad. Sorry to hear about your Camaro.”

“You better get that firewood before they sell out.”

They watched him make his way to the door, stopping twice to talk to other out-of-work men seated at the tables.

“I don’t think he’s doing so good,” Randy said.

Zeke’s kids were grown, his house mostly paid for. At least Zeke’s wife still cooked his meals. At least Zeke’s wife hadn’t come out of the blue one evening, telling him she’d had enough after all they’d been through. Brad shrugged. “He’ll be all right.”

“I’d have gone for the ham and eggs, if I’d known you were buying,” Lee said.

“You can still order ’em. Say, where’s your brother? Have you seen him lately?”

Lee chewed a toothpick, let out a sigh. “Not since the other day.”

“He was supposed to meet us. I guess he had a better offer.”

Randy leaned in. He’d been best man at Brad’s wedding. “Your brother should pace himself,” he told Lee. “He’ll still be wanting that pussy when he’s sixty.”

“You tell him. I can’t tell him anything.”

The waitress, Zetta, breezed in with a fresh pot of coffee. “What else can I get you boys?”

“Ham and eggs for him and me,” Brad said. “Randy?”

“I’ll have some, too, if he’s buying.”

* * *

Lee slammed down his ham and eggs, finished his coffee, and said he needed to pick up formula and diapers for the baby. Brad stood and embraced his son.

“Too bad about the Camaro,” Lee said without looking his dad in the eye.

“It’s just a car.”

“Yeah, right.”

Brad knew it was only a matter of time before Lee left town with his family. He was already talking about Austin, Texas or Madison, Wisconsin, places where they were still hiring. Lee had told Brad he was welcome to come along, hang out with his grandchildren until something turned up. But Brad wasn’t moving—that was for young folks, moving for a job, not old guys like him.

“Good kid,” Randy said, when Brad returned to his seat.

“He’s always been a good kid. It’s that other one I worry about.”

Brad paid the check and left a twenty-five percent tip, feeling flush with the cash. The two men lit up just outside the door. Brad pointed to the black Ford-250 across the parking lot.

“That really is a piece of shit,” Randy said. There was rust on the running boards and dings on the fenders.

“It gets me from place to place.”

“Remember that time we cut school and took your Camaro to Chicago. Two hicks from Indiana cruising Lake Shore Drive.”

“Snow on the ground, two weeks into baseball season.”

“Sun was out, though. Sox lost their game that day.”

Randy threw his cigarette to the pavement and ground out the butt with the toe of his work boot. “I don’t know if you heard, but Dale Yoder’s back from Florida.”

Brad let it sink in. “Why should I care about Dale Yoder?”

“Word has it he’s working in a warehouse in Fort Wayne.”

Fort Wayne was only two hours away, down old US 33, three hours in winter with snow drifting across the road as high as your wheel wells. “It’s none of my business. Sherry wants nothing to do with him.”

Randy slapped Brad on the shoulder. “Just thought you’d want to know. I’ll see you around.”

“Not if I see you first.”

Randy set off for his Jeep. He’d driven Jeeps all his life, usually holding onto them way too long. This one needed new tires and a new windshield—Randy’s teenager had put a BB shot through the passenger’s side.

Brad fired up his new truck and dropped it into gear. It still smelled of the man who’d driven it before, his cigarettes, his sweat. The truck lurched, sputtered, then came to halt. That clutch was going to take some getting used to.

He crossed the bridge at the dam, headed up Prairie to Middlebury Street, then turned and cruised down Goshen Avenue back into town. His boy, Ray, lived in one of the old houses along here, but Brad wasn’t sure which one. This part of town had been nice once, with big, old two stories overlooking the Little Elkhart. Then the blacks moved in, and after them the Hispanics, several families bunking up in one house. Most recently, with no work to be found, the spics had abandoned the houses to cocaine dealers and meth cookers. One of the houses had burned down recently. People stood in the street watching the flames, snatching hundred dollar bills out of the smoke. Drug money.

Brad had hoped to see Ray sitting on a porch or walking down the sidewalk, but the avenue was quiet, not even a crack addict to be seen. He wouldn’t have known what to say anyway.

* * *

He found his father working in the yard with a rake. The thing was, the trees hadn’t dropped their leaves, yet. “Sold it to Kenny Lorenz?” the old man asked.

“They were going for between twenty-six five and sixty thousand on the internet,” Brad explained. “Kenny offered forty.”

The old man hadn’t bothered to put his teeth in that morning. Coffee stains streaked his chin and graying white t-shirt. “I never expected you to sell that car.”

“Had to,” Brad said. ‘My unemployment runs out next month.”

Brad had been a senior in high school, the old man in his forties, when they’d bought her. She’d been sitting on the lot, cherry red with black pin-striping, a 327 engine and four on the floor. The old man had wanted her as bad as Brad.

“That car was clean inside and out. Not a nick or scratch, original interior and engine.”

“Yeah,” Brad agreed. “She was clean.”

The old man leaned on his rake. He’d worked forty years as a butcher, breaking down beef quarters into steaks and chops, standing in sawdust and blood. In those days, a man could make a living like that, own a decent house, raise a family on a journeyman’s wage.

“The President says they’re pouring money into town. He says green is the way to go.”

“I’m not even sure what that means,” Brad said.

“Well, if you don’t know, I sure as hell don’t.”

“How come you’re raking leaves when the leaves haven’t dropped?”

The old man flashed a toothless grin. “Getting a head start.”

It didn’t make any sense, but at the old man’s age maybe it didn’t have to.

* * *

Brad spent most of the afternoon clearing the lot behind his RV. The two acres of land he’d bought from Randy’s uncle for next to nothing. The RV was used, a 1980’s Nomad with a kitchen and toilet. The propane heater worked well enough on cool nights. Brad wasn’t so sure how it would stand up to twenty-below come January.

The lot behind the trailer was a thicket of pine, maple, mulberry, and thorny underbrush. Brad liked the rip and roar of the chainsaw, the solid feeling of accomplishment that came from slicing the trees and bushes into manageable pieces. When he’d finished cutting, he dragged and stacked the pieces into neat piles. Next, he’d have to borrow Zeke’s tractor and pull the stumps. Then he could bush-hog, rake, and level. If he found work, he wanted to build a house here, something simple, something clean, like the Camaro.

Just before dinnertime, he showered and put on a new pair of jeans, a flannel shirt, and the black down vest Lee had given him for Christmas. He’d turn fifty-seven in March, but he didn’t look as old as he remembered people looking at that age when he was a kid. His grandfather on his dad’s side had been stooped and old at sixty. His mother’s father died before hitting seventy. Brad’s hair, cut close on the sides and top, showed a few strands of gray, his face bore wrinkles around the eyes, and his gut was bigger than it used to be. Not that much bigger. He still looked strong and healthy. Able. He’d quit smoking for twenty years only to re-start after losing his job.

Sherry Yoder was the one got him going on cigarettes again. She tended bar at Rainbow, but back in high school she’d been a cheerleader and Brad had played football on a team that made a run at the state championship. People expected them to marry, but while Brad cruised the drag in his Camaro, Sherry slipped off and married Dale Yoder. She and Dale divorced about the same time Brad and his ex-wife Brenda filed.

After the divorce, Dale left town and Brad ran into Sherry at one night at Rainbow. Like he’d told Randy, one thing led to another. Now, Dale was back, working and living in Fort Wayne.

Brad opened a Miller Lite and carried it onto his stoop. He could make out the last of the sunset behind the trees. Beneath the stretch of gray cloud, pink faded to red, then a deeper red, then a cherry red. When he finished his beer, he stood and winged the bottle against a maple tree twenty feet away, shattering the glass into a thousand heartless shards.

* * *

“You sold the Camaro?” Sherry said between pours. “You sold your fucking car?”

Brad was drinking Maker’s Mark. On top of dinner at the bar—two cheeseburgers, chili with extra Jalapenos, and fries—the whiskey gave him a warm glow, gave Sherry and the entire bar a warm glow. She looked good with that great smile, natural blonde hair, and curves in all the right places.

“I owned her for a long time. I was time to pass her on,” Brad said.

“Damn, I loved that car. The first time we ever did it was in that car.”

When she faced Brad, he could see her ass in the mirror, firm and round. It was the kind of ass a man could get behind. “I’m not thinking about the first time,” he said. “I’m thinking about the next time.”

Sherry slapped his hand and feigned embarrassment. “So, how’re you getting around?”

“New pick-up.”

“What’d you get? One of those new Fords? I love that midnight blue color.”

“It gets me where I’m going. What time you get off tonight?”

“You know what time I get off. I get off when the last drunk rolls out of here.”

“I was hoping maybe I could come over.”

“Not tonight, Brad. Have you forgot what it’s like to work a full day?”

He tossed back the last of his Maker’s Mark. It was all he could do to keep from winging the glass across the room like he’d winged that beer bottle into the maple tree. “Well, I think I’ll call it a night.”

Sherry kissed him on the cheek. “Buzz me tomorrow. I’ll be around.”

He was halfway across the parking lot when he recognized the man walking his way. Dale Yoder had played on the same football team as Brad and Randy Miller. Dale had made a good tight end, beefy yet fast. He still walked with the same farmer’s gait from forty years ago.

“Goddamn, if it isn’t Brad Phillips.”

“Hey, Dale.”

The two men shook hands. “Jesus,” Dale said. “It’s been years.”

“I heard you went to Florida.”

“I’m over in Fort Wayne, now. My kids are still here.”

Brad reached for a cigarette, shook it out. “Yeah, and Sherry’s here.”

Dale jammed his hands into his jeans pockets and hunched his shoulders. “It’s a free fucking country.”

Brad lit the cigarette and inhaled deeply. “Yeah, it is.”

Neither man spoke for a moment, then Dale said, “Say, you still own that cherry red Camaro? Man, that was a nice car.”

Brad wanted to hit him hard enough to hurt him, drive him to the ground, and send him to the hospital. “Nah, I sold it. Got an offer I couldn’t refuse.”

Dale grinned. “You can’t beat that with a stick.”

“Yeah, you can.”

* * *

Brad found the evening Northfolk and Southern at Lusher and South Main. He followed it east, his window down, despite the cold. He stayed close then edged even when the freight, two diesel engines pulling over a hundred a cars, passed the last gated crossing at County Road 11. Back in the day, there had been little traffic and few houses out this way. Now there were subdivisions, a new school, and strip malls on the other side of the tracks.

Out past County Road 15, the traffic thinned, the lights few and far between. Housing developments gave way to corn fields, the farm homes and barns long abandoned. Some of the corn had been picked already and the fields lay empty, except for stalks cut nearly to the ground. Brad slowed, but didn’t stop at the last four-way. He downshifted, then goosed the pick-up.

The freight gained speed, but Brad stayed with it. The crossing where he’d waited with the Camaro early that morning lay just ahead. He was doing seventy, the truck’s engine whining, when he shot ahead of the train. He’d gained a quarter mile cushion, maybe more, when he downshifted again and cut the wheel hard to the right.

The pick-up fishtailed, the ass-end nearly slipping away. He braked hard, squared up at the crossing, popped the clutch, and goosed the Ford again. He’d have made it with plenty of room to spare if the sonofabitch hadn’t died half way across the tracks, just like she’d died at the Waterfall. For the rest of his life Brad would remember the next few moments; how he’d felt the train’s great light bearing down on him like a dragon’s fiery breath, how he’d managed to restart, shift, and lurch forward just clear as the freight, whistle blaring, wheels clanking, roared past. Balding tires skidded on gravel, and juiced on adrenaline he overreacted, sending the truck into a one-eighty that left him facing the track.

He collapsed into his seat, heart pounding. He didn’t budge until the caboose rocked past. He opened the cab door, stepped free of the rusted running boards, and threw up in the ditch. Bent over, hands on his knees, he gave it a minute before wiping his mouth on his sleeve and returning to the truck. He rested his elbows on the hood and watched the caboose’s lights far out of sight. With the train gone, the only sound remaining was that of a lone cricket singing in the brush.

He slipped inside the truck’s cab and started her up. He was thinking that at least he had an RV to hunker down in and cash in his pocket. He was thinking that if push came to shove, he could move to Austin, take the old man with him, and leave Ray on his own. Lee was right—no one could tell Ray anything anyway.

He’d soaked his shirt with sweat and felt a sudden chill. He’d probably catch pneumonia. He closed his window and set the heat on high. He looked both ways and eased onto the tracks. She wasn’t the Camaro, but she wasn’t such a bad truck. At least the heat worked.

Brad dug inside his pocket for his crumpled cigarette pack. He gave it a shake, pulled one from the pack with his lips, and punched the lighter. But by the time the lighter responded, he’d decided to quit smoking. Instead of lighting up, he tossed the cigarette aside.

It was one more thing he could do without.

Brad lit a cigarette, sat on the hood of his cherry red’68 Camaro, and waited for the morning freight, a double-stacked car carrier, to pass. Halfway between Elkhart and Goshen this was one of the last remaining crossings without gates; only a standard crossbuck marked the tracks. In years past there had been accidents here followed by talk of gates and better lighting, but with train traffic down and money short, the talk had stopped. When both Brad and the Camaro had been younger, they’d played a game, racing trains along the county road running parallel to the tracks, then cutting in front at the crossing, seeing how close they could pass to that sick grind of steel on steel.

You know, just for the hell of it.

Winter was coming on. He could feel it in the cold, damp air, see it in the white-gray sky that would remain mostly the same until spring. In years past, winter had meant shoveling out and rigging chains on tires just so a man could get through. This year, it meant mounting heat bills and cabin fever. Before long, his unemployment would run out, and he wasn’t sure what that meant. He hunched his shoulders and sunk a little deeper into his old Pea coat.

The Camaro was the last thing left to sell. His ex-wife had taken the furniture, the TV, and his bass boat. All he’d wanted after thirty years was that cherry red Camaro.

* * *

The Waterfall diner near the Johnson Street dam was as full as it would have been for breakfast in the old days, except this wasn’t breakfast time. This was ten o’clock in the morning, and these weren’t men on their way to work. These were men laid off, caught up in a wave they hadn’t seen coming and couldn’t outrun. Brad scooched in next to his oldest boy, Lee, across from Randy Miller and Zeke Cramer. He’d worked with Randy and Zeke at the Nomad plant, Randy in cabinets and Zeke in sidewall, from the plant’s start-up in the ’80s until it’s closing a few months earlier. Lee had stayed on at the lumber yard until the week before.

In his early thirties, with a wife and two kids of his own, Lee spoke to his old man from behind a cup of coffee. “So, did you do, it?”

Brad nodded. He was a big man, six-two and two-fifty, with calloused hands, muscular shoulders and arms, and a thick chest. He’d been Nomad’s roofer, assembling and setting twenty, twenty-five roofs a day, when business was good. “Yeah, I did it.”

Lee turned away and stared out the window.

Zeke dug inside his ear. “Zowee,” he said. A fat man with a weak chin, he was getting fatter by the minute now that he had more time to devote to his eating. He wore overhauls tucked inside his yellow boots, the kind firemen wore.

Randy, tall and lean, with a graying handle-bar mustache, spoke in a deep bass voice. “So, how much did you get?”

Brad reached into his pocket and brought forth a roll of cash bound by a rubber band. He set it on the table. “Forty thou, give or take a little. It’s down to thirty-five now. I bought a piece-of-shit pick-up to get around in at Yoder’s Ford.”

Randy shook a cigarette out of his pack, then tucked it behind his ear. Smoking was no longer allowed at the Waterfall. “That cherry red Camaro. The first time we got laid was in that Camaro.”

Lee grinned. “Come on, you got laid?”

“Once, smart-ass,” Randy said.

Brad ignored the BS, Randy and Lee always going after each other, and retrieved his roll of cash. “Anyway, it’s done.”

Zeke stood and pulled his Harley Motorcycle cap down on his forehead. “I gotta see a man about some firewood.”

“Maybe you should move south,” Randy said. “Somewhere you don’t have to pay for heat.”

“I was thinking of wintering in Tahiti, myself,” Lee said. “I hear the women go topless there.”

Zeke dropped three dollars on the table to cover his coffee. “You can get that down at Night Moves.”

“Not for free, though.” Randy and Lee had it in unison.

Brad shoved the three bills back in Zeke’s direction. “This one’s on me.”

Zeke winced, but retrieved his money. “Thanks, Brad. Sorry to hear about your Camaro.”

“You better get that firewood before they sell out.”

They watched him make his way to the door, stopping twice to talk to other out-of-work men seated at the tables.

“I don’t think he’s doing so good,” Randy said.

Zeke’s kids were grown, his house mostly paid for. At least Zeke’s wife still cooked his meals. At least Zeke’s wife hadn’t come out of the blue one evening, telling him she’d had enough after all they’d been through. Brad shrugged. “He’ll be all right.”

“I’d have gone for the ham and eggs, if I’d known you were buying,” Lee said.

“You can still order ’em. Say, where’s your brother? Have you seen him lately?”

Lee chewed a toothpick, let out a sigh. “Not since the other day.”

“He was supposed to meet us. I guess he had a better offer.”

Randy leaned in. He’d been best man at Brad’s wedding. “Your brother should pace himself,” he told Lee. “He’ll still be wanting that pussy when he’s sixty.”

“You tell him. I can’t tell him anything.”

The waitress, Zetta, breezed in with a fresh pot of coffee. “What else can I get you boys?”

“Ham and eggs for him and me,” Brad said. “Randy?”

“I’ll have some, too, if he’s buying.”

* * *

Lee slammed down his ham and eggs, finished his coffee, and said he needed to pick up formula and diapers for the baby. Brad stood and embraced his son.

“Too bad about the Camaro,” Lee said without looking his dad in the eye.

“It’s just a car.”

“Yeah, right.”

Brad knew it was only a matter of time before Lee left town with his family. He was already talking about Austin, Texas or Madison, Wisconsin, places where they were still hiring. Lee had told Brad he was welcome to come along, hang out with his grandchildren until something turned up. But Brad wasn’t moving—that was for young folks, moving for a job, not old guys like him.

“Good kid,” Randy said, when Brad returned to his seat.

“He’s always been a good kid. It’s that other one I worry about.”

Brad paid the check and left a twenty-five percent tip, feeling flush with the cash. The two men lit up just outside the door. Brad pointed to the black Ford-250 across the parking lot.

“That really is a piece of shit,” Randy said. There was rust on the running boards and dings on the fenders.

“It gets me from place to place.”

“Remember that time we cut school and took your Camaro to Chicago. Two hicks from Indiana cruising Lake Shore Drive.”

“Snow on the ground, two weeks into baseball season.”

“Sun was out, though. Sox lost their game that day.”

Randy threw his cigarette to the pavement and ground out the butt with the toe of his work boot. “I don’t know if you heard, but Dale Yoder’s back from Florida.”

Brad let it sink in. “Why should I care about Dale Yoder?”

“Word has it he’s working in a warehouse in Fort Wayne.”

Fort Wayne was only two hours away, down old US 33, three hours in winter with snow drifting across the road as high as your wheel wells. “It’s none of my business. Sherry wants nothing to do with him.”

Randy slapped Brad on the shoulder. “Just thought you’d want to know. I’ll see you around.”

“Not if I see you first.”

Randy set off for his Jeep. He’d driven Jeeps all his life, usually holding onto them way too long. This one needed new tires and a new windshield—Randy’s teenager had put a BB shot through the passenger’s side.

Brad fired up his new truck and dropped it into gear. It still smelled of the man who’d driven it before, his cigarettes, his sweat. The truck lurched, sputtered, then came to halt. That clutch was going to take some getting used to.

He crossed the bridge at the dam, headed up Prairie to Middlebury Street, then turned and cruised down Goshen Avenue back into town. His boy, Ray, lived in one of the old houses along here, but Brad wasn’t sure which one. This part of town had been nice once, with big, old two stories overlooking the Little Elkhart. Then the blacks moved in, and after them the Hispanics, several families bunking up in one house. Most recently, with no work to be found, the spics had abandoned the houses to cocaine dealers and meth cookers. One of the houses had burned down recently. People stood in the street watching the flames, snatching hundred dollar bills out of the smoke. Drug money.

Brad had hoped to see Ray sitting on a porch or walking down the sidewalk, but the avenue was quiet, not even a crack addict to be seen. He wouldn’t have known what to say anyway.

* * *

He found his father working in the yard with a rake. The thing was, the trees hadn’t dropped their leaves, yet. “Sold it to Kenny Lorenz?” the old man asked.

“They were going for between twenty-six five and sixty thousand on the internet,” Brad explained. “Kenny offered forty.”

The old man hadn’t bothered to put his teeth in that morning. Coffee stains streaked his chin and graying white t-shirt. “I never expected you to sell that car.”

“Had to,” Brad said. ‘My unemployment runs out next month.”

Brad had been a senior in high school, the old man in his forties, when they’d bought her. She’d been sitting on the lot, cherry red with black pin-striping, a 327 engine and four on the floor. The old man had wanted her as bad as Brad.

“That car was clean inside and out. Not a nick or scratch, original interior and engine.”

“Yeah,” Brad agreed. “She was clean.”

The old man leaned on his rake. He’d worked forty years as a butcher, breaking down beef quarters into steaks and chops, standing in sawdust and blood. In those days, a man could make a living like that, own a decent house, raise a family on a journeyman’s wage.

“The President says they’re pouring money into town. He says green is the way to go.”

“I’m not even sure what that means,” Brad said.

“Well, if you don’t know, I sure as hell don’t.”

“How come you’re raking leaves when the leaves haven’t dropped?”

The old man flashed a toothless grin. “Getting a head start.”

It didn’t make any sense, but at the old man’s age maybe it didn’t have to.

* * *

Brad spent most of the afternoon clearing the lot behind his RV. The two acres of land he’d bought from Randy’s uncle for next to nothing. The RV was used, a 1980’s Nomad with a kitchen and toilet. The propane heater worked well enough on cool nights. Brad wasn’t so sure how it would stand up to twenty-below come January.

The lot behind the trailer was a thicket of pine, maple, mulberry, and thorny underbrush. Brad liked the rip and roar of the chainsaw, the solid feeling of accomplishment that came from slicing the trees and bushes into manageable pieces. When he’d finished cutting, he dragged and stacked the pieces into neat piles. Next, he’d have to borrow Zeke’s tractor and pull the stumps. Then he could bush-hog, rake, and level. If he found work, he wanted to build a house here, something simple, something clean, like the Camaro.

Just before dinnertime, he showered and put on a new pair of jeans, a flannel shirt, and the black down vest Lee had given him for Christmas. He’d turn fifty-seven in March, but he didn’t look as old as he remembered people looking at that age when he was a kid. His grandfather on his dad’s side had been stooped and old at sixty. His mother’s father died before hitting seventy. Brad’s hair, cut close on the sides and top, showed a few strands of gray, his face bore wrinkles around the eyes, and his gut was bigger than it used to be. Not that much bigger. He still looked strong and healthy. Able. He’d quit smoking for twenty years only to re-start after losing his job.

Sherry Yoder was the one got him going on cigarettes again. She tended bar at Rainbow, but back in high school she’d been a cheerleader and Brad had played football on a team that made a run at the state championship. People expected them to marry, but while Brad cruised the drag in his Camaro, Sherry slipped off and married Dale Yoder. She and Dale divorced about the same time Brad and his ex-wife Brenda filed.

After the divorce, Dale left town and Brad ran into Sherry at one night at Rainbow. Like he’d told Randy, one thing led to another. Now, Dale was back, working and living in Fort Wayne.

Brad opened a Miller Lite and carried it onto his stoop. He could make out the last of the sunset behind the trees. Beneath the stretch of gray cloud, pink faded to red, then a deeper red, then a cherry red. When he finished his beer, he stood and winged the bottle against a maple tree twenty feet away, shattering the glass into a thousand heartless shards.

* * *

“You sold the Camaro?” Sherry said between pours. “You sold your fucking car?”

Brad was drinking Maker’s Mark. On top of dinner at the bar—two cheeseburgers, chili with extra Jalapenos, and fries—the whiskey gave him a warm glow, gave Sherry and the entire bar a warm glow. She looked good with that great smile, natural blonde hair, and curves in all the right places.

“I owned her for a long time. I was time to pass her on,” Brad said.

“Damn, I loved that car. The first time we ever did it was in that car.”

When she faced Brad, he could see her ass in the mirror, firm and round. It was the kind of ass a man could get behind. “I’m not thinking about the first time,” he said. “I’m thinking about the next time.”

Sherry slapped his hand and feigned embarrassment. “So, how’re you getting around?”

“New pick-up.”

“What’d you get? One of those new Fords? I love that midnight blue color.”

“It gets me where I’m going. What time you get off tonight?”

“You know what time I get off. I get off when the last drunk rolls out of here.”

“I was hoping maybe I could come over.”

“Not tonight, Brad. Have you forgot what it’s like to work a full day?”

He tossed back the last of his Maker’s Mark. It was all he could do to keep from winging the glass across the room like he’d winged that beer bottle into the maple tree. “Well, I think I’ll call it a night.”

Sherry kissed him on the cheek. “Buzz me tomorrow. I’ll be around.”

He was halfway across the parking lot when he recognized the man walking his way. Dale Yoder had played on the same football team as Brad and Randy Miller. Dale had made a good tight end, beefy yet fast. He still walked with the same farmer’s gait from forty years ago.

“Goddamn, if it isn’t Brad Phillips.”

“Hey, Dale.”

The two men shook hands. “Jesus,” Dale said. “It’s been years.”

“I heard you went to Florida.”

“I’m over in Fort Wayne, now. My kids are still here.”

Brad reached for a cigarette, shook it out. “Yeah, and Sherry’s here.”

Dale jammed his hands into his jeans pockets and hunched his shoulders. “It’s a free fucking country.”

Brad lit the cigarette and inhaled deeply. “Yeah, it is.”

Neither man spoke for a moment, then Dale said, “Say, you still own that cherry red Camaro? Man, that was a nice car.”

Brad wanted to hit him hard enough to hurt him, drive him to the ground, and send him to the hospital. “Nah, I sold it. Got an offer I couldn’t refuse.”

Dale grinned. “You can’t beat that with a stick.”

“Yeah, you can.”

* * *

Brad found the evening Northfolk and Southern at Lusher and South Main. He followed it east, his window down, despite the cold. He stayed close then edged even when the freight, two diesel engines pulling over a hundred a cars, passed the last gated crossing at County Road 11. Back in the day, there had been little traffic and few houses out this way. Now there were subdivisions, a new school, and strip malls on the other side of the tracks.

Out past County Road 15, the traffic thinned, the lights few and far between. Housing developments gave way to corn fields, the farm homes and barns long abandoned. Some of the corn had been picked already and the fields lay empty, except for stalks cut nearly to the ground. Brad slowed, but didn’t stop at the last four-way. He downshifted, then goosed the pick-up.

The freight gained speed, but Brad stayed with it. The crossing where he’d waited with the Camaro early that morning lay just ahead. He was doing seventy, the truck’s engine whining, when he shot ahead of the train. He’d gained a quarter mile cushion, maybe more, when he downshifted again and cut the wheel hard to the right.

The pick-up fishtailed, the ass-end nearly slipping away. He braked hard, squared up at the crossing, popped the clutch, and goosed the Ford again. He’d have made it with plenty of room to spare if the sonofabitch hadn’t died half way across the tracks, just like she’d died at the Waterfall. For the rest of his life Brad would remember the next few moments; how he’d felt the train’s great light bearing down on him like a dragon’s fiery breath, how he’d managed to restart, shift, and lurch forward just clear as the freight, whistle blaring, wheels clanking, roared past. Balding tires skidded on gravel, and juiced on adrenaline he overreacted, sending the truck into a one-eighty that left him facing the track.

He collapsed into his seat, heart pounding. He didn’t budge until the caboose rocked past. He opened the cab door, stepped free of the rusted running boards, and threw up in the ditch. Bent over, hands on his knees, he gave it a minute before wiping his mouth on his sleeve and returning to the truck. He rested his elbows on the hood and watched the caboose’s lights far out of sight. With the train gone, the only sound remaining was that of a lone cricket singing in the brush.

He slipped inside the truck’s cab and started her up. He was thinking that at least he had an RV to hunker down in and cash in his pocket. He was thinking that if push came to shove, he could move to Austin, take the old man with him, and leave Ray on his own. Lee was right—no one could tell Ray anything anyway.

He’d soaked his shirt with sweat and felt a sudden chill. He’d probably catch pneumonia. He closed his window and set the heat on high. He looked both ways and eased onto the tracks. She wasn’t the Camaro, but she wasn’t such a bad truck. At least the heat worked.

Brad dug inside his pocket for his crumpled cigarette pack. He gave it a shake, pulled one from the pack with his lips, and punched the lighter. But by the time the lighter responded, he’d decided to quit smoking. Instead of lighting up, he tossed the cigarette aside.

It was one more thing he could do without.