Bicentennial

Jay Duret

The Reporter

Shortly before the nation’s bicentennial, a wave of graffiti washed over Philadelphia. Before long it came to the attention of A. Edward Jaffe. In those days Jaffe was still the features editor of the Bulletin. He was a skinny man of fifty with bad, bad breath like he stunk inside. He’d been with the paper forever. We all called him Jaffe, like taffy, no matter how young we were; I had the feeling that he liked me as well as a guy like Jaffe would ever like anybody.

I was the scholarship kid at the Bulletin that year. This was in the days before the paper was sold out of the General’s family and it still had all the prizes and promotions and programs that had begun in the days when the Bulletin was the paper nearly everybody read. I had been editor of the school paper at St. Francis Xavier. At the end of my senior year I won the Bulletin Prize for Journalism; it paid my tuition to St. Joe’s during the day and gave me a job at the Bulletin at night. I won for an article I’d written about Bobby Beck, a ten year old kid with a speech impediment from East Falls who spray painted his name on virtually every bridge and sign in Philadelphia. I called the story King of Graffiti. I actually came in third in the contest but the first two winners decided to leave the city for college.

I’d have left too if I’d known how shitty the job was. I wrote death notices, what we called “slot” obituaries. The day crew talked to the bereaved families and put together files of notes and clippings. If the decedent was of sufficient note in the eyes of Ellie Baumgarten to merit an article, the day crew wrote it up. But if the stiff was a corner Joe from Kensington or a retired pharmacist from South Philly, they left the file on my desk — sometimes twenty or thirty of them — and I composed the final words that sent him to everlasting peace:

SPUTNAM

May 9, 1976, suddenly, YETTA (nee Springstein) beloved wife of George D., survived by a daughter,

Barbara, one grandson and one granddaughter, 4 sisters and a brother. Relatives and friends are invited

to funeral Tuesday, May l2, 9 A.M., precisely, JOSEPH T. SACKS FUNERAL HOME, INC., Twenty-second

Street and Olney Avenue. Contributions in memory to American Cancer Society.

They said they were getting a computer to do the job, but I didn’t believe Ellie Baumgarten. Sometimes the day crew dumped on me and wouldn’t fill out the forms and I had to take wild guesses at the names of the survivors from scrawl on envelopes and match packs. I hated it. Sometimes I amused myself by writing obituaries in the style of the Personals from Philadelphia Magazine:

TALL WHITE MALE, honestly good looking, 72, intelligent, attractive and cultured, sought attractive,

trim, exciting female for enjoying life, cuddling, sharing, laughing, people. Reply Plot 3232 White-Wetzel

Funeral Home, December 9 at 9:00 A.M. Photo not required.

But it wasn’t that amusing late at night when everyone had gone home except me and I was surrounded with the dead. Yetta Sputnum? Had she trembled with modesty and love and anticipation when she first stood naked before George D.? Had she screamed with delight when Barbara came bawling into life? Had she fought at the end, or did she go gentle into the obituaries? You can see how it could get a person down. Grown people and when they died their whole lives squeezed neatly into the skinny slots I specialized in drafting. Was that all there was? Born, beloved, and gone, survived by others?

I couldn’t get out of the job. The paper had money trouble and it discontinued the Bulletin Prize for Journalism after my year so there was no new drone to take over. I hung around the real reporters when I could and sometimes submitted stories I’d worked up but they were never acknowledged. If I could have paid for school any other way I’d have been long gone, but I couldn’t, so I ground the stuff out night after night until I met the dead in my dreams.

The Artist

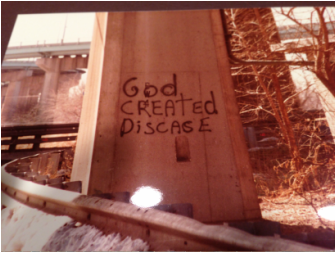

At first I worked on a small scale; I scratched the message into toilet stalls and telephone booths throughout the city. I wrote, “God Lies.” I wrote, “God Created Disease.” But as the Spring sprang into summer and the blooms fell from the azaleas behind the Art Museum, my tableau expanded. Toilet walls no longer. I festooned the bridges abutting the Schuylkill Expressway.

I was learning my medium. I did not have the mastery for which I longed, but I grew from day to day. The city spread itself before me like the taut white skin of a canvas. Who can describe the vastness of the possibility that awaited. Nothing less than cleansing fire. The way cleared for true expression. Not magic, my friends. Not religion. I’m talking about Art.

The Reporter

One night Jaffe called me into the glass booth where he holed up at the far end of the old newsroom.

“You’re the one that did that graffiti story, right?” he said, biting a flap of skin on his knuckle, looking at me in my reflection in the glass.

“Excuse me?”

“You’re the graffiti guy aren’t you? Didn’t you write that shit about Billy Bob or whatever the hell his name was huh?”

“Oh. Bobby Beck, yes sir. When I was in high school. Two years ago.”

Jaffe looked at me directly, still biting his knuckle. His left eye ticked a mile a minute. “You want another graffiti story?”

“Yes sir. I’d like any story. A graffiti story would be fine. Just fine.”

He gave me a bitter smile and scaled a pack of 8 x 10 photos at me. They sliced through the air in all directions. I scrambled to pick them up and saw the pictures were of bridges covered with graffiti. “God Created Disease.” “God Lies.”

“Hey” I said brightly, “this stuff’s all over the city lately, have you noticed?”

Jaffe sighed in his patented way. “What I want you to do” he said, “is write me a nice clean eight hundred word filler to go between the pictures in the Sunday Supp. If you can get those things right, everything will be ok. Nice and clean and eight hundred words.”

“Sure I . . .”

He cut me off with a hand. “We’re going to print a few of these pictures, and I need some nice little filler to go between. Something nice and bland and eight hundred words. I do not want anything provocative. I do not want anything vital. I especially do not want anything essential. Just cream of wheat. That’s what I want.” He went back to biting his knuckle. He looked like Billy Martin brooding in the dugout.

I began to back out of the booth, but I couldn’t resist. “I’ll give you just what you want. Eight hundred words. Cream of wheat. And don’t you worry, sir, I’ll give it a nice fresh slant. . .”

He whirled toward me but I was already on the run out through the newsroom, past desk after empty desk of reporters and editors and circulation people, past the obit files and my cubbyhole, out onto Market Street and summer in the city. I had a story. Finally.

Philosopher or pervert? That’s the question the men in blue are asking about the graffiti artist who

has rocked the City with a stream of graffiti in the last few months. Not that the bridges and trolleys

and billboards of Philadelphia have ever been free of the swirls and pomp of the artists of graffiti. But

the simple declaratives of the past, “John loves Maureen,” “Kilroy was here,” have given way to a

roadside invective about the Lord that many find troubling, if not obscene. A bridge on I-95 near the

Girard Avenue Exit proclaims “God Cheats at Poker.” Two exits later, the graffiti artist has written “God

Lies.” And near the Spectrum a poster proclaims that “God’s Tongue is Forked.”

Officer Raymond Kronswizck of the 15th District finds the signs offensive. “The fellow is a sicko, I’d say,”

the lanky six-year veteran says, “kids on the way to school got to go past that stuff. What do they want

to go reading God Lies or God does this or that. They’re just little kids. Guy’s got to be a little sicko.”

Tom Tucker, a meat-packer at Quaker City Meats and a long-time user of the Section of Route 95

where much of the graffiti has appeared, agrees wholeheartedly. “You never know what they’ll do next.

Now this. Now that. Then this again. And why? You never know. And by this time next year you still won’t

know. That’s what I think.”

The new graffiti has caused consternation because it connects the Lord to various corrupt activities

and ascribes to Him cruel or pornographic intent. “God Created Disease” appears several times along the

Schuylkill Expressway. Sometimes the last word is spelled properly but more often it is “Discase” or

“Disase.” Other, harsher judgments are found on West River Drive. “God S—-” and “God Eats It.”

Officer Kronswizck reports that the police are looking into the matter but he is reluctant to predict

when, if ever, the culprit will be apprehended. “It’s really up to the neighborhood people to let us know

if someone comes around writing dirty things,” he says.

Sandy Stiller lives directly across the street from a yellow traffic sign in Kensington that once bore the

legend “God’s A Mobster.” Now that sign is no more. “We, I mean, the Community felt as though we

couldn’t let that just stand there,” says Mrs. Stiller, a pretty blond dental hygienist and mother of two,

“we felt we had to do something. First we were going to spray over the sign but we were afraid that it

would confuse motorists. So we just took it down.”

Asked if she had any idea what motivated the artist to this kind of graffiti, Mrs. Stiller said she didn’t

understand it “but maybe it’s part of that music where the boys put safety pins in their ears.”

Twenty-six year old Ray Johnson from West Philadelphia disagreed. “Like, its expression, you know.

Man’s a little cranky about the church. Maybe someone done him something wrong there.”

Temple University sociologist Barry Hendler thought the motivation might come from the current social

malaise about religion. While Hendler had not seen the graffiti, he theorized that “perhaps the artist is

trying to shock us back into the days when religion was a fundamental part of our lives. Modern society at

times seems to have outstripped the organized religions. Many individuals who, in the past, would have

been faithful are now left without guidance.”

“Perhaps,” Hendler hypothesized in his book cluttered office in Temple’s Lipton Arts Building, “the artist

— or should we say author — has suffered a personal tragedy and is unable to absorb the fact that no one is

at fault for his suffering.”

Thomas Paul Swaine, noted advocate of liberal causes in Philadelphia and former counsel to the “Dirty

Dozen” pointed out during a telephone interview that the Constitution provides that no State shall make

any law abridging the freedom of expression. “While the Government can make reasonable laws regulating

the time, place and manner of speech, it cannot be outlawed on the basis of what it says,” the noted

advocate explained. “If the artist is apprehended it will be interesting to see if he’ll be prosecuted for

what his graffiti says or just for defacing public property. We’ll just have to see,” Swaine concluded, leaving

no doubt that he and the liberal community will be waiting to see what brand of justice is meted out to this

citizen.

Philosopher or pervert? No ready answer appears to this vexing question.

Jaffe cut hell out of my effort and sent me back to the obits where the files had been collecting for three days. If you lost a relative in that period, I apologize for the delay. But two weeks later, after I’d almost given up hope, a 500-word article appeared in the Supp under my by-line. It filled up two pages spread dead center with a photo in each corner.

I didn’t want to act like a kid around the Bulletin, but when my story appeared, I went out and spent $6.00 on the Sunday edition. I stacked the Supps in my room at my parents’ house and I can still remember the powerful pleased feeling I had going to sleep with the papers stacked neat beside my bed. “Like bonds in the bank” I told myself, “bonds in the bank.”

The Rewrite Man

Funny, just as I saw the story in the Bulletin I was rememberin’ back a few nights ago coming back from Artie’s place after the AA meeting. I was coming down the ramp from 95 near Aramingo and suddenly I saw this big sign painted in red like dripping blood on the wall: “God Lies.” Gave me such a start when I seen it. And later I was thinkin’ about it, thinking about how it shouldn’t jus be sitting there, and damn if I don’t spread open the magazine right straight to a story called The New Graffiti. They din’t have a picture of the bridge I saw but it was the same stuff for sure.

In the days when I was drinkin’, I wouldn’t of cared. Hell there wasn’t many a Sunday morning when I could manage to read the paper even. But since these days when I’m better now and starting to get rid of the worst of the longing, it makes me real mad. If you don’t have the Lord all you’ve got’s the bottle. That’s the only choice and Nancy agrees with me. Having that baloney sign out there made me feel bad you know. Like watchin’ someone beat up on a girl. Or like you read in New York about a crowd standin’ by while a nurse gets stabbed.

So I got Artie on the phone and read him the story. I specially read him the part about the philosopher stuff cause I knew that’d get him, Artie don’t like no philosophers. He said “so whatcha wanna do Danny?” And I told him I wanted to get us some paint and fix up the damn stuff. Artie thought it over a little and then says he’s agreeable. He even says that we should take his camera along and get some pictures. “Maybe they’ll do another story in the newspaper.” Artie’s always tryin’ to figure an angle like that. He’s got this little run-down restaurant in South Philly which he says would be a gold mine if he could get a little publicity. I told him that’s okay with me but I didn’t want to get in no trouble on account of me havin’ a city job. He said he understood. So we agreed.

The Reporter

The week after my story came out I fought desperately to keep my glory to myself, but I found excuse after excuse to stroll down to the far end of the pressroom by Jaffe’s glass house on the chance that he wanted to rush out and pump my hand and give me an assignment that would take me to Madrid or Tokyo or even Conshohocken. But each time I passed by, he was bent over his desk in that nervous way he had like he was secretly eating the papers in front of him. He never looked up.

The worst agony came at 8:00 p.m. I would have been at my desk since 5:30, coming straight from school, coming a half hour early, my dinner a cheesesteak I picked up on the way, thinking for sure tonight Jaffe’d give me another story. And then at 8:00 seeing him walking across the far end of the pressroom in his ratty raincoat hurrying for the fire stairs we were not supposed to use, and then he was gone and my chest would contract and I felt like crying. I turned to my desk and the long hours until I could leave stretched before me like an abandoned city street and I went back to the slots.

JAFFE

June 8, 1976. A. EDWARD, suddenly of a mysterious ailment to the joy of all who knew him. Relatives and

friends invited to dance on the grave of the son of a bitch, 9:00 P.M. June l3, 1976 until the liquor gives

out.

About ten days after my story appeared, I found a yellow message slip on my desk when I came in. It said that Arthur Lock had called that afternoon. No return number, but the “Will Call Again” box was checked.

Not many people called me at the Bulletin and it was always bad news. Ellie Baumgarten referred all complaints about the obits to me whether or not I was responsible. And so I would get the calls from the grief-distraught wife whose lawyer-husband’s demise had destroyed her purchase on civility, and try to explain why our obituary had praised the deceased’s work for the American Barn Association. I tried to avoid taking the calls, but if they were persistent they always got me. Arthur Lock did too. On the third night I made the mistake of picking up the phone.

“Is this Barrow?” That was my last name, Barrow. “Didn’t you get my messages? This is Artie Lock. I’m tryin’ to do you a favor.”

“What,” I said.

I heard him take a deep breath. “I been trying to reach you for a week on account of that story of yours about the graffiti.”

“Oh” I said, the light dawning. “I’m awfully sorry. I’ve been trying to duck someone. I apologize for your inconvenience.”

“Don’t sweat it,” he said, “I know how it is.”

“What can I do for you Mr. Lock?”

“The graffiti story. I’ve got an idea for you.”

“What idea is that?”

“I’d like us to get together and talk it over.”

At school they taught us to milk telephone callers over the phone before racing off to some futile assignation, but I couldn’t resist; no one had ever wanted to talk to me before.

“Where? When?”

“I’m over at Cavenaugh’s now. Any chance you could come over?”

Cavenaugh’s was across the street. We called it the Cave.

“Sure,” I said, “see you in a few minutes.”

The Artist

I was sadly disappointed by the first of the newspaper articles. There was no depth to the effort, no eye. It is all too easy to be perplexed in this world by opposing views, but only through merger and integration are new spaces formed. Yet the critic could not visualize the melting together. Only the buzzing windows in the box. Sad. A ripped canvas.

At first I was discouraged that the newspapers had picked up on my work. How much of the power would be spent by the time the papers finished pummeling the images? How many people would lose the clutch and release they would experience if they had come upon the works fresh, unsullied by the paper jockeys, came upon them the way they were designed to be discovered?

I thought of abandoning the bicentennial series altogether. But then I experienced one of those rare moments when my mind plugged into the great Volksgeist and I could view my concerns from a richer perspective. The truth of the matter was that I couldn’t ask for a better integration of my works and the community. Wasn’t that the idea? How could I have hoped that the work would remain unsullied like chaste paintings in naked museums. Of course the papers would muddy the meaning, just as the grime and soot of the city would coat the words I painted and render them difficult to read. What else could Art in the city be? What else was Art in life?

The Rewrite Man

Artie came over tonight and tole me ‘n Nancy this funny story about him goin’ to see the newspaper guy at the Bulletin. Seems like Artie was ‘specting one of those red-nosed Irish guys like you can see down at the courthouse on the big trials, you know, someone who’d been ’round. Instead this teenage guy name of Bill Barrow comes racin’ over to meet Artie all hot to get a tip.

Artie had took with him some snapshots of the two signs that we doctored up last Thursday, but for some reason the flash didn’ work and the pictures didn’ come out so hot. You could tell what we done but they was kinda dark.

Anyway Artie handed the kid the pictures and said that he had some information for the kid about what had happened. The kid looked the pictures over like he didn’t get it, but then he gets real excited askin’ a million questions at once like where were these taken and when were they taken and why were they taken and did Artie take them and on and on. Artie said he’d never heard so many questions pouring outta one person.

Artie’s smooth about these things, I guess cause he’s always tryin’ to get into the papers, so he doesn’t tell the kid too much. Just wants to get his interest wet. He tells me ‘n Nancy that he figures he can work the thing into a headline story if he plays his cards right. Me, I don’ much care about the newspaper though I get a kick outta Artie gettin’ so excited. Him and me we goes way back together from the neighborhood, same as brothers.

Anyway Artie sizes the kid up real quick and figures that the kid is real wrapped up in this philosopher angle like he had in the paper. So Artie tells the kid that he can’t tell him who took the pictures or who fixed up the graffiti or anythin’ except that he is a professor guy that’s got a different philosophy than the usual bums.

You shoulda seen Artie tellin’ the story — he gets such a blast out of it — he seen the kid takes to the whole thing hook and sinker. The kid gets Artie to give him the addresses where the new signs are. He says he’s gonna to take a look and maybe get some better pictures. He wants to know how come Artie knows all this and Artie says that he thinks its part of public responsibility to make sure the public knows both sides of da story. Artie says that he thinks there may be more developments in the in the next weeks and that he’ll try to keep the kid advised of what’s goin’ on. The kid thanks him and gives Artie his home phone number to call if he gets any hot tips.

So now Artie’s got all these plans.

The Artist

Process can be a metaphor for expression. I was driving down I-95 early this morning hoping to get a shot at the bridge by Graterford before the morning traffic started. I had been there the day before making sketches and planning how to execute the final version. Coming back into the city in my old Ford I took a minute to stop and review one of my first works on the Girard Ramp divider. It had been inspiration, that one. The wall had been brand new and empty of graffiti. There isn’t much down that end of the city except vacant lots the city owns and warehouses. Usually I spend a lot of time studying the site, listening for what the neighborhood has to tell, imagining what road someone would be traveling when he’d come to this point, figuring whether it would be May time or a time of dark figures. Usually it takes days, sometimes weeks.

But this wall, I saw it and I knew exactly what and how and why. I pulled over, got out a can of cinnamon car body spray paint I bought at Penn Jersey and in the square bold strokes they use in Lima to announce ¡HUELGA! I quickly painted “God’s a Slob.”

I was pleased. The wrecked neighborhood, the ineffectual curse, the picture of a man whose answer knew bounds. Maybe the lettering was a bit too squared at the top (as if the man had a grim sense of determination) — this was some of the criticism I heard later — but I really didn’t think so. It was one of my best early efforts.

This morning I went past the same spot where I was yesterday afternoon. But when I glanced over I saw that someone had defaced the work over night. I could not believe it. The work had not been just crossed out like some of the ones in Kensington. This one had been edited. Half the cinnamon had been covered up with black paint; over top of the cross-out there was this Tom Sawyer-style wide brush scrawl so the whole thing now read: “God’s a live.”

I was upset. It’s one thing to live with the newspapers diluting the meaning of a work of art, another altogether to live with Nazi destruction of Art. Book burning scum.

Yet, my friend, what could I do? Art is not permanent. It does not last. I know that.

My sense of humor came back by lunch. I went out in broad daylight and casually painted the letter “r” in bright red at the end of the defaced work. It wasn’t perfect by any means, but the pun blended well with the motif of the original creation. It even got me thinking whether the concept of defacement ought not to be expressed in some of the original works. That got me onto the idea of ritual defacement, which kept me busy sketching through the day and well into the humid city night.

The Reporter

One night in June Jaffe appeared at my desk, his nervous face twisted in a knot. He slapped a black and white photograph onto my desk. Graffiti on a wall. You could only barely read it: “God Fucks Us All Over.” It looked like a record album cover for a punk band.

“Know where this is?” Jaffe snarled, pointing with his smoke stained hand. His fingers were so full of tobacco you could snap one off and smoke it.

I pretended to study the picture. “No, sir.”

“Guess.”

“Looks like the wall of a building somewhere.”

“Doesn’t look familiar?”

Actually it did, sort of.

“It’s thirty feet from your fat head, Barlow.”

“The Bulletin building?” I asked with surprise. “When?”

Jaffe’s eyes ticked like a clock. I looked at the picture more carefully, knowing he wouldn’t answer. “Its a pun,” I said but he was already on his way back to his hole. He was no Ben Bradlee, the shithead. I started to worry more about the story I’d given him a couple of days before. Yet I needn’t have, cause that Sunday on the last page of the Supp under a banner which said “Following Up. . .” in big black letters the following article appeared:

The new wave of Philadelphia graffiti described in William Barrow’s article in the June 2nd edition of

this magazine has apparently become the target of a “counter graffiti” artist.

The original graffiti on the Girard Avenue Exit of I-95 no longer reads “God Kills.” Now the bold red

words proclaim “God’s skills are many.”

And three miles to the North, painted on an abutment near the Dietz and Watson plant, a many color

sign says “God is Good.” A few weeks ago the same abutment bore the legend “God is a Pig,” and D & W

manager Joe Ferguson had planned to send out a work crew to paint the epithet over.

But before Ferguson could take that step, the new language appeared. “Miraculous” said one D & W

worker. The burly plant manager offered a less cosmic explanation. “I’m not surprised, that graffiti was a

disgrace. Someone beat me to it, that’s all.”

When asked if he planned to send his work crew to paint over the edited graffiti, Ferguson was

incredulous. “What for,” he said, “God is Good, and you better believe it.”

Bulletin readers have recently observed at least three other locations where the “new graffiti” has

been edited. Yet the identity of the counter artist or artists is as uncertain as that of the original artist.

Police say they have no new information and continue to look for any person defacing public or private

property. Asked whether that description would cover a person “editing” existing graffiti, the police

spokesman declined to express an opinion.

The Rewrite Man

Funny how much graffiti’s around once you start noticin’ I guess when I was drinkin’ I never really looked around much but these days lookin’ for all the graffiti about God I been noticin’ how much of Philadelphia is covered with spray paint. Wonder why exactly people want to go to so much trouble to spray their names all around. I don’t much ever remember doin’ it growin’ up in the neighborhood though I guess I remember writin’ girls names in the streets with chalk and even in wet cement. But I wasn’t no webhead type of guy wants his own name everywhere people doin’ their business.

Whit the bicentennial coming up in a couple a weeks you’d think they’d be putting more attention to this stuff. But I guess you live in the city long enough you don even notice it. Least not unless its foul stuff like the sicko’s. Nobody’d fail to notice that.

We been havin’ a ball. After Artie and me got a couple a bridges the first night and had such a good time, we took Nancy and Carol out whit us. Just like one of those dates we’d go on in school. Me ‘n Nancy up front whit the windows down and the radio on looking for a place to park; Artie and Carol giggling and wrestling in the back. Every so often Nancy leaning back to see what they was doing.

We’d pull us up in some quiet place off the road and sneak out with a paintbrush and a bucket of city paint. Hidin’ in the bushes until the road was clear and one of us dasht out and paint’d like crazy until we saw headlights. Then we’d dash for cover till the car’d be gone. The girls enjoyed it as much as us guys. Haven’t had so much fun in years, they both said. Fact is, durin’ the day while we was workin’ they got together a couple a times and drove all over tryin’ to find all the graffiti about God in the area.

They figured we was gonna clean up all this guy’s graffiti sooner or later, but they weren’t right about that I was pretty sure. We could get 2 or 3 or maybe 4 places a night and there was really only one night we could all get together with Nance workin’ nights lately.

But I wasn’t much concerned, cause I had a new plan, a much better one. One day I passed by the first of the places where we cleaned up the graffiti. The sign used to say “God’s a Slob” but we made it read “Gods a live.” Next time I passed by I noticed further changes. Now it said “Gods a liver“. I got to figurin’ who did that and I started thinkin’ that’s the stupid kind of remark of the scumbum himself. Might just be that we was getting him mad and that he’d be back to make changes in the signs we done. Which’d mean that we could stake out one of them places and grab the sicko when he came out. It was an idea.

Anyway, I changed the “1″ in the word liver to a “g” and resolved to come back in a couple of days and see if there was anymore change. And when I did, I found, sure enough, that the sign said “God’s a giver of shit.” I made “shit” into “life” and decided to tell Artie bout my idea and see if he wanted to try to nail the sucker. Personally, I’d like to give the guttersnipe a kick in the nuts.

The Artist

Effacement, defacement, erasement, debasement, had they ever been understood in Art before? Not as forces that operated on art, against art, to art. But as the movement within, the piccolo and the chariot? Art has been plundered of the concepts that apply in the outside world. We do not even have a phrase for the concept of planning the obsolescence of a work. But in the gimcrack wiseapple business world they’ve known it, used it, understood it forever. This series is teaching me things I never imagined.

The Reporter

“Will” said the thick voice on the phone, “I’ve got an idea for ya.”

“Oh yeah. What is it Mr. Lock.”

“Heh now, none of that Mr. Lock business. I tole you to call me Artie.”

“Oh sure, Artie. What’s up?”

“Well you see, I was thinking you might not a noticed but them places where the original graffiti got changed, you know, where I showed you the pictures of?”

“I’m with you.”

“Well the guy’s going around changing ‘em all.”

“Who is?”

“The dirtball, the original guy. The scumbag himself.”

“How do you know?”

“I been checking for you Will. I know you been busy so I been checking for you. Like there was this one in my neighborhood, big red sign on an abandoned house all boarded up used to say ‘God’s flower is evil,’ somethin like that.”

“Baudelaire, now.”

“Nah. Right on the front of the house. Well a couple days ago it got doctored up, real philosophical-like, so it says ‘God’s flower is evil destroyed.”

“Wordy.”

“Huh . . . yeah but now its changed again. Says ‘God’s flower is evil destroyed by suffering.

“Where is it?”

“28th and Naudain. But you see the idea I got is this. . .”

The Reporter

I began looking that same night after work. In school they always taught us to maintain a certain healthy skepticism about our sources and I had plenty of suspicions about Artie Lock for sure. His idea was good, but I didn’t let on. Noncommittal, professional in tone, I didn’t take the bait. The last thing I wanted to do was spend a night camped out under some overpass with Artie Lock and his bad cigars and dirty jokes, his nudges and pant-splitting flatulence, waiting for the King of Graffiti to come by.

But the idea was good, for sure. So I cruised around the city until I found the perfect spot. On East River Drive, just short of the grandstand where the crowds sit to watch the rowers on Skimmer Weekend, there is a big dirty city-style bridge that the King had visited. I was taken with the graffiti he left and I parked up the drive and walked back to study it.

The bridge was so accustomed to graffiti that he couldn’t find space to write so he first painted out a big white square on the west wall, like a canvas, and then he penned the line in bright red on the white spot. The red hadn’t run so he must have waited until the white was totally dry before he wrote. The line was in delicate script, as if engraved on jewelry or written with a fountain pen calligraphy — not the usual scrawl of the broad brush artist or spray gun clown. White canvas, flowing red line:

“God Drinks the Blood of Puppy Dogs.”

The location couldn’t have been better chosen. The Drive bends just before the bridge as you drive into the city and as you come around the bend there at once in your headlights is the bridge and bang on the wall is the sign in blood red. God and puppies. Blood and water. Death in the City.

Across the Drive a cliff rose from the road. I climbed my way around and up and found a sneaky little spot that kids must use as a drinking spot, a flat little clearing where I could sit and just see the base of the bridge and the river beyond. I began to think of what I’d need, and how I’d look in the next Supp when my picture would be appearing with my exclusive photos of the graffiti artist at work.

The Artist

Celebration of Art. Not cerebration or congratulation. Not inebriation or procreation. Not time or the mixing of words. I couldn’t believe what was happening. My series, my bicentennial series I had called it, liking the gaudy commercial ring, was dead letter these days. Not a series, a celebration. Art not as the fixing of the moment, a still point in a turning world, not that at all. Art as celebration. The process of art, the collective creation, the consciousness of living art in a tumbling world, had happened. I’d never have known it on my own. Not until the stakes had been raised, not until my idea had been pushed, broke open, flung in my face.

It was no longer a bicentennial memorial to art in the city as I had originally wanted – what a cheap Gershwin-esqe idea that had been. Oh yes, the stakes had been raised. Now instead there was a real bicentennial gift, a true memorial, the waking of art in the collective slumbering mind of the city, the lumbering stuttering grope of a gigantic consciousness popping the pins of restraint. That was my work. That was what I had started. Imagine then my delight when they reached my masterwork. I couldn’t contain myself, I thought I’d broken blood vessels in my brain. I almost — what is the expression — pissed my pants, yes, true, I almost pissed my pants. For there on the river bridge it now said as clear as a bright whistle on a summer day “God Loves Puppy Dogs.” The word “Loves” in bold blue. It was so good I couldn’t believe it.

The Rewrite Man

“Danny oh Danny boy he took it he fuckin’ took it.” “Artie?” My watch said 2:00 a.m.

“He took it Danny, he fuckin’ took the bait. He just left his apartment. And guess what he had slunk over his back?”

Nancy had her head in on my arm. She’d sleep through tornados, she could. “I’ll bite.”

“Back pack. And he had all sorts of camera stuff. Tripods and stuff.”

“Good.” Man I was sleepy.

“Oh shit I knew it was him that got that bridge with the puppies. He thinks he’s stealing our idea. We got him Danny! We got his ass now!”

“So whatcha gonna do?”

“We’re gonna watch him, fellah. We’re gonna be there when the kid catches the scum-bum and we’re gonna be heros and we’re gonna be in the papers like princes. You and me.

“Artie, I can’ be in no papers. You know that. I got a city job. No way I’m gonna blow a city job.

“Oh Danny don’t ya see, this is gonna getcha a medal. They’ll probably promote your ass, hah! You’re probably the next fucking Chief of L & I.”

“Arg…”

“Danny, come on Danny, this is what we’ve been waitin’ for. For months what, come on don’t let me down now fellah.”

“Oh shit Artie, it’s two in the morning. Talk tomorrow.”

“Oh no big fellah. Now’s the time. I’ll be there in ten minutes. Get your fat ass in gear.”

“Artie, Artie don’ please don’.” He’d hung up. Fucknoodle. I was not in the mood.

The Reporter

When I was a boy I lived in Fairmount and we’d go down to the Schuylkill with these gummed up sticks and strings, fishing we said. We mostly just hung down by the water smoking cigarettes where no one could see us, bitching about the sisters at school, giving each other shit. Now and again we’d pull something out of the brown oily water, but nothing ever to keep. They’d be monsters more likely than fish. Flappy river rats, weird floppy wildebeests. One kind that got all puffy and sallow like a leather change bag and no one would put their hands on it to get it off the hook. Sometimes the same damn fish would come back to the hook again and again as if it liked to get yanked from the river, manhandled by us and flung with a splash into the unguent water. Yanked, handled and flung. Cheap thrills.

It was cold on the rocks overlooking the river and I couldn’t find a soft spot to sit. I really wanted to get into my sleeping bag but I was afraid I’d fall asleep. I wasn’t sure I could keep this up. All day at school, then at the paper squeezing the dead into slots, and then camped out on this cliff waiting for the damn graffiti artist to show up. I’d been two days at it already. And no one had showed. Last night I had watched with my binoculars as a couple with a blanket walked to the river’s edge and actually did it right there. Did it. That was pretty interesting though even with the binos all you could really see was this big white globe bumping up and down.

I spent a lot of time trying to figure which way the King of Graffiti would come from and what I’d do when he arrived. I had got Kenny to lend me a camera with a long lens and special slow film for the dark. Each night I’d put it on the tripod and get it all fixed up so that I had only to push a plunger on a cable where I was sitting and it’d shoot pictures like mad, but I didn’t really know much about cameras. I was reluctant to rely on any damn machine. What I really wanted to do was get the guy cold. After two nights of debating I figured that I would shoot as many snaps as possible and then climb down the hill and grab the guy or follow him or whatever. I had to get his name and find out where he lived and then I was home free. That is, if he showed up.

Actually, I admit that I didn’t spend all that much time thinking about what I was going to do when he showed up. I kept imagining the story after. I couldn’t get it out of my head. This was my big break. A once in a lifetime shot. And even Jaffe wouldn’t try to keep me out of it, I was part of the story now, when I caught the guy I’d be right in the thick of it.

I could see it now, not only a multi-page article — and this one would not be cream-of-wheat, you could bet on that — there’d be a profile, maybe in a boxed section on the first page of the story, maybe even on different color paper. A profile for sure about the journalist that had broken the story. And a picture. A color picture. I could see it:

Twice this summer these pages have featured stories by Bulletin scholarship reporter William

Barrow about a new type of graffiti in Philadelphia. In the first of those articles, Barrow, a student and

journalism major at St. Joseph’s University, reported that a wave of graffiti connecting the Lord to

various corrupt activities had swept through the City this summer. “God Lies,” “God Created Disease”

and even viler epithets were found in foot high letters painted on bridges and billboards from the

Delaware River to the Schuylkill.

Following up on his earlier reporting, Barrow later wrote of the emergence of what was apparently

a “counter-graffiti” artist who had begun to systematically change the messages left by the original

artist.

While Barrow’s articles were generally well received, a few of our readers complained that Barrow

and the Bulletin had, albeit unintentionally, fostered further graffiti in the City just at the time that

Philadelphia was sprucing itself up for its role as host for the nation’s bicentennial celebration. Indeed

the Bulletin building itself was the target of several incidents of vandalism, perhaps related to Barrow’s

journalism.

Barrow took the incidents in stride. Despite his hectic schedule of school and other work at the

paper, Barrow pursued the story. Ever astute, the young journalist noticed that the messages left by the

counter graffiti artist were themselves the object of graffiti. Studying the contents of the messages,

Barrow was quick to surmise that the second defacements were done by the original graffiti artist

himself. And so Barrow decided that if he could find a fresh example of the counter artist’s work he would

only have to wait and bide his time before the original artist would return.

And this is just what Will Barrow did. Night after night, he spent the time when others were sleeping

camped in a cramped hiding place waiting for the artist to return. And then one night, late in the night,

the artist indeed did return, and the story beginning on the facing page unfolded.

We at the Bulletin are proud to have a Will Barrow on the staff and our readers have much to look

forward to as this young journalist’s career continues in Philadelphia.

I wondered whether they’d let me write the profile myself. Probably one of the editors would take it on, maybe Jaffe would do it. After all, Jaffe first spotted the story. And even if he hadn’t been too quick to understand its importance, he’d been there through the thick of it. He deserved the honor.

The Rewrite Man

I tole Artie I wasn’t gonna go no more after this night. That the whole thing was gettin’ outta hand. He and me we wasn’t no kids no more, we got jobs and families and couldn’t be spendin’ our damn nights in no gazebo — that’s what Artie called it — a gazebo, in Fairmont Park — spying on the reporter kid while he was spying on the damn bridge. Cold and tired and Artie always jabberin’ away next to me about how we was gonna be heros and how he had the kid with the goods alright and how Artie could get him to write whatever we damn well wanted and how I was gonna get my promotion. Shit, Artie gettin’ so worked up that I’d hafta run for mayor.

I finally had to tell him no more. We go out one more time and that’s it. Even Nancy ain’t so pleased with the idea no more, not with me sneakin’ around and sleepin’ at dinner with my face in my hand like I used to when I was drinking. Even she has about had it with Artie’s plan and she was always sweet on Artie ‘specially since Artie got me into the AA with him just when things were really starting to get bad and Suzie ran off to California with that gutterbum from Fishtown.

Tonight’s the last night for me for sure. No matter what Artie says. An then I’m gonna sleep the whole damn holiday through. And if I get up at all on the damn fourth of July I’m gonna move no further than the TV and watch me the goddamn hoopla from my own living room. And that’s that.

The Artist

According to the accounts in the papers, the courts ruled that the city had no authority, no jurisdiction in the primal sense of the word, to interfere with big Fourth of July anti-parade sponsored by the “Get the Rich Off Our Backs Coalition.” Yet somehow the city managed to arrange that the anti-parade would never get near the real parade down at Independence Square. Seems the anti-parade will be out of the city, out of sight. And out of mind too just like in the homily. But the symbol was too clear for me to miss. Not that it was anything new. Hegel saw it all in his stubborn Teutonic fashion long ago. The push and the response and the springing burst of new ideas onto the world, not the still moment, but the unending squeeze of process. Not a parade alone. But parade and anti-parade and out of the two the springing flash of awareness. The way cleared for true expression. No, not magic, my friends. Not religion. Not that either. I’m talking about Art.

Squeezed thus by the forces of parade and anti, by history and celebration, my time had been chosen. I would return to the master work. And complete the project. Which is to say that I would continue the process of my art into a new beginning. An anti-beginning. Tonight then, my friends.

The Reporter

It was the night of July 3, 1976. I knew he would come. It was time. No graffiti artist could pass up a chance like the coverage that could be had tomorrow. My God, it was to be the 4th of July, Independence Day. The Bicentennial. The biggest party Philly had ever seen. Live TV all over the world. Right from the heart of the birthplace of liberty. And liberty was what this graffiti was about.

I had figured that out.

Freedom not from God, but from the idea of God. From trust in the world beyond. From the conviction that all would be well in the end. That was what the graffiti artist was saying. No, doing. He was liberating people. Not from God — from Him they were already free — but from the idea of God. Liberty in the terrifying sense.

And if I was right, if I had finally understood, he’d certainly come tonight, on the eve of Independence Day.

The Rewrite Man

It was four o’clock in the morning. Four o’clock in the fuckin’ gazebo. Artie was snoozed out too. This is the last one I said to myself for certain. The last night. Soon as the damn sun comes up, home for sleep.

I was standin’ in the damn gazebo, every so often peerin’ over the rail to make sure the Reporter was there. Course he was. Still as a brick. Wrapped up in his sleeping bag. Probably on the snooze too. I was probably the only damn one of us awake. And wishin’ I had a damn bottle to lend a little warming.

Figuring on it I couldn’t understand how Artie talked me into all this. All the hero stuff. I knew that was bullshit. No newspaper want to write bout guys like me an Artie. We was neighborhood kids. Not no hotshot lawyers or horse racers. But Artie he had this angle. Artie always got some angle. He tells me that he’s got the kid with the goods that he can make the kid write whatever we want. He’s even got some of it written already and he’s got photos too. Me with my tie on in Sunday clothes and Nancy with a new perm standing besides me all fixed up and everything.

Artie figures he can make the kid put the stuff in the paper. Maybe he’s right. Artie, he says that the kid took the bait and cause the kid didn’t want to go with us he had to find a spot on his own. But then the bum wouldn’t come there unless his graffiti had been edited like we done.

So the kid makes a big mistake. He finds the graffiti on the bridge and in order to get the crud to show up the kid he goes out and squirrel’s up the crum’s graffiti. The kid he goes and does just what we done. He changes the graffiti on his own.

Artie, he says that this means the kid went too far to get the story. He set up the graffiti guy — all beyond journalism rules or something. Artie says it means that the kid will have to take us in with him when we tell him we know what he was up to.

Entrapment. That’s what Artie calls it. We could blow the kid’s story Artie says. Me, I don’ know one way or the other but Artie figures these angles pretty good.

So Artie says we just wait til the kid gets the crud and then we get the kid and then we lay back and be heros. I read it. The stuff Artie wrote:

The cat is out of the bag. Finally, the story can be told. How Artie Lock of 417 Sandbury Street

and Daniel Dorcom who lives at 483 Mulberry Street singlehandedly captured the criminal and vandal that

was scuzzing up the City of Brotherly Love right at the time of the Big Bicentennial Birthday Party. Artie

Lock, the owner and manager of Lock and Key, one of the finest and most upper-crust restaurants in the

City (where Councilman Steel and Singer Tony Sanka are often seen dining to their stomachs’ delite) has

this to say about their daring adventure. “Danny and I we thought that we ought to do something about

some of the crap that was going on in the City so we could help make it a better place for us to live and

raise up our families into honest decent Americans. And so we decided we would make our stand with this

guy. If the little guy doesn’t stand up and fight then we are all going to lose. Well Danny and me we

stood up and fought and by God we won!”

Danny Dorcom, one of the senior guys in the city Department of Licenses and Inspections, explained

that for him the job doesn’t end when the quitting whistle blows. He said that he’s on the job 24 hours a

day and sometimes more making sure that the city is working the way it should. “I just couldn’t stand by

and let it happen,” Danny was quoted as saying.

Artie had a lot more written but I forget the rest of it. Sure would knock the socks off the guys at L and I, wouldn’t it? Specially that 24-hour a day business and more, that was a good one. Artie always could think ‘em up.

But it doesn’t look like we’re gettin’ no story now, where was the guy? I took another look over the edge of gazebo to check. Funny, the kid had moved. Hard to tell, looked like he was kneelin’ or something. Like he was checkin’ the bridge out. Maybe I better get Artie out of the snooze.

The Reporter

About 4:30 a.m. I finished my 9th cup of coffee, cleaning out the second thermos, and I was still sleepy. I picked up the binoculars and scanned the bridge for the hundredth or thousandth time. My teeth chattering. Suddenly my teeth stopped and so did my heart. I saw him.

A man, walking by himself on the grass about twenty yards from the bridge. He was wearing one of those green army field jackets. Hands in his pockets. He was turned away from me. He had black hair over the collar of the jacket. A little bald spot on top, bluejeans. He was looking at the bridge. Right at the graffiti. He was standing there looking right at the graffiti, not moving just staring right at it.

My God, it was him. I was sure of it.

I checked the camera. All ready. As soon as he moved forward a little, as soon as he pulled his painting stuff from those big pockets, I was going to start snapping pictures. He was just about in range.

And as soon as I got the pictures I was going to leap down the hill and nail him.

My God, it really was him. After all the waiting I couldn’t believe it. “Come on man” I said to myself “Come on, get to it.”

I watched him carefully. He wasn’t moving. I looked up the drive. No one was coming. A summer night in the City. Quiet, dark. The black wind blowing. “Come on, Come on.” It must be him.

He stood stock still. The binoculars hurt my eyes. What was he waiting for? “Come on shithead come on,” I breathed.

The Artist

Merger, integration, a growing moment. The work with an internal luminescence spreading from its core. I was transfixed on the grass, a coin toss from the work. The slap solid white backing, the prose spindly in red like a Hallmark card or an iced message on birthday cake. This had been the best of all of them: God Drinks the Blood of Puppy Dogs. Not puppies, puppy dogs. That boyish phrase graven as it were into the rank graffiti covered structure, one foot in the river’s dank belly, the other across the road; legs on a colossal colossus, branded with a script, the footnote of history. Not hasty impermanent conjecture, but a final summary, a pronouncement. The judgment of history. But . . .

There was something about the change, so temporal, so hoaky, so supremely silly: God Loves Puppy Dogs. My God, the colors. Red and Blue on the White. A flag. The American bicentennial falsetto. I was awed. The power of it. Not a God that was stupidly cruel, not malignant, not the Jaweh of the First Testament, not a God of death and the wretched retching river. Not this at all. No, not this at all. Something better, deeper, ultimately more satisfying.

A God that loves puppy dogs. I began to laugh. It was truly better this way. I couldn’t improve on this.

The Reporter

He couldn’t! But he was. He was walking away. He hadn’t touched the graffiti. He was walking away, oh shit, he was walking away.

It wasn’t him.

It wasn’t him after all.

The Rewrite Man

For a minute I thought that maybe somethin’ was really gonna’ happen. The kid he’d got all excited. He was hoppin’ up and down like a pogo stick. Seemed like he saw somethin’. I even got Artie outta the snooze and everything but then nothin’ even happened. The kid he just got back into the sleepin’ bag and that was that. Nothin’.

We waited some more but then the sun started coming up and we picked up our things and went on home. I was lookin’ forward to some real sleepin’. Artie, he felt pretty bad but I tole him there’d be another time; we’d get the sicko one day.

The Reporter

Only later did I think that maybe it had been him. Maybe he’d come. Maybe there’d been a change deep in his heart. I kicked myself for not going after him. Maybe he had just given up. Decided that from this idea of God there was no liberation. But I couldn’t make it sensible. And so I went back to the death notices, writing the slots for those that had died on July 1 and 2, the epithets for those that hadn’t quite lasted to Independence Day. But I wasn’t disappointed. The lack of sleep made me giddy and in that mood I did something I never did before. I snuck a slot that I’d made up into the paper. Ellie Baumgarten never even noticed. You can see it if you’re interested. It’s right there in the Bulletin:

LORD

July 4, 1976, inevitably, THE, beloved husband of Faith, survived by the rest of us. Relatives and friends

are invited to remember that He created obituaries. No services planned.

May His slot fit.